“Kyrie Eleison along the road that I must travel…” ~ Mr. Mister

Liam James is undoubtedly a kindred spirit to many young men because he’s the epitome of awkward. His posture is terminally awful. He has no confidence, no presence, his hair could use a trim, and he’s pale and unassertive. He doesn’t even have a go-to dance move, heaven forbid. He’s the kind of kid who wears jeans to the beach in the throes of summer.

But that’s what we have at face value. The problem is he plays into the narrative that others have written for him and it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy. Take Trent (Steve Carell), the man Duncan’s mother (Toni Colette) is seeing. He calls the boy out on his apparent lack of social skills and criticizes him for being a 3 on a scale from 1 to 10.

That’s what Ducan has to go up against as his makeshift family travels to the beachfront for summer vacation. It looks like a dead end, several months that Duncan will simply have to survive tagging along awkwardly with Trent’s self-absorbed teenage daughter or getting systematically belittled by Trent in small ways.

And yet this same summer that looks like a veritable disaster ends up becoming the most formative time in Duncan’s life because in the thick of all the bad stacked up against him he is introduced to a world of so much good. It’s one of those moments of sheer happenstance. He begins riding a pink bicycle around town to get away from the suffocation at home and finds himself crossing paths with everyone’s new favorite friend Owen (Sam Rockwell).

They meet over a Pac-Man game and it’s awkward. Because every conversation Duncan has is awkward (ie. He talks to his pretty next-door neighbor Susannah about the weather). But not about to give up on a kid in need of some camaraderie, Owen lets the lad into his life and offers him something remarkable: A job helping him at the water park Wizz World.

In itself cleaning up vomit and stacking chairs isn’t the image of a perfect summer. But by reaching out and giving Duncan something, Owen impacts someone else more than he will ever know. Because that park represents so much for Duncan. It’s the family he’s struggling to find. It’s his fountain of confidence. It provides him a much-needed platform where even he can be cool and be known by others. That’s what we all want, to be known and appreciated.

That’s why he returns again and again. In fact, it’s so apparent how often he rides off that Susannah (AnnaSophia Robb) follows him one day and the rest is history. This girl who is different than her peers begins to take an interest in his paradise because she sees a confidence and enthusiasm in him that never existed before and she too seeks an escape.

Meanwhile, Duncan’s home life is still a shambles. Things are shot to hell as Trent is cheating on his mother and their vacation gets quickly terminated. He’s unhappy with it all and there’s very little his mother can do about the situation. Forced to say goodbye to the best family he ever had, there’s still some satisfaction in one last trip to the water park.

He emblazons his name forever in the lore of Wizz World and he gets the joy of Owen facing down Trent. Perhaps most importantly, the ride in the way-back of the station wagon is a little less lonely on the return trip. His mother has made the concerted effort to be by his side which is a statement of her new resolve to hold their family unit together.

This film is a dream. No one would go so far as to say that this is the dream summer or the dream job but it is a bit of a fantasy and we wish it could be true. Because Wizz World much like Adventureland (2009) before it is an oasis from the worries and distractions of the world at large. It’s one of those places frozen in time year in and year out, in this case, stuck permanently in the 1980s. But this Neverland, far from stunting your growth, helps one teenager discover more of his confidence than he ever thought possible.

Likewise, Sam Rockwell is a cinematic creation, the voice we always wish we had, the cool guy we wish we had in our corner, the jokester who helps us become a better version of ourselves by bringing us out of our shells. In some ways, he’s Peter Pan. Because if he existed in reality, it would only be depressing, but here there’s a special aura about him that instantly makes him our favorite character.

Meanwhile, Steve Carell much to his credit shows another side of himself and even greater range as an actor as Trent, a man who can best be described as a Grade-A jerk. Still, there’s something tragic in the characterization. Everyone else from Maya Rudolph a fellow Wizz World manager, Allison Janney the uninhibited mom-next-door living life buzzed, or even writer/director partners Nat Faxon and Jim Rash, all utilize their various quirks and qualities to stand out. Even Rob Corddry and Amanda Peet while playing a pair of obnoxious friends manage to leave their marks on those roles that feel surprisingly believable.

Faxon and Rash’s previous effort The Descendants (2011) is the kind of film that got award buzz and it’s a searing drama that’s almost brutal in impact. Whereas The Way Way Back is made for summer. It’s light, funny, full of life while still managing to be poignant. Coming-of-age nostalgia pieces are a personal weakness — a guilty pleasure even — and this film hits that sweet spot. Are there flaws? Yes, but why focus on those when there’s so much that’s refreshing like a summer vacation of old that you took with your family or ventures to the water park with your best friends? Sometimes we need films like this.

4/5 Stars

There’s a moment in Kelly Fremon Craig’s The Edge of Seventeen where Nadine (Hailee Steinfeld) suffers the ultimate humiliation third wheeling with her older brother Darian (Blake Jenner) and her (former) best friend Krista (Haley Lu Richardson). Needless to say, the evening is less than stellar but it gets worse after Nadine feels like she’s been totally betrayed. She’s been hating her brother recently and her best friend is dead to her now. The fact that she sets up an ultimatum doesn’t make things any better.

There’s a moment in Kelly Fremon Craig’s The Edge of Seventeen where Nadine (Hailee Steinfeld) suffers the ultimate humiliation third wheeling with her older brother Darian (Blake Jenner) and her (former) best friend Krista (Haley Lu Richardson). Needless to say, the evening is less than stellar but it gets worse after Nadine feels like she’s been totally betrayed. She’s been hating her brother recently and her best friend is dead to her now. The fact that she sets up an ultimatum doesn’t make things any better. In his noted Crisis of Confidence Speech, incumbent president Jimmy Carter urged America that they were at a turning point in history: The path that leads to fragmentation and self-interest, down that road lies a mistaken idea of freedom. It is a certain route to failure.

In his noted Crisis of Confidence Speech, incumbent president Jimmy Carter urged America that they were at a turning point in history: The path that leads to fragmentation and self-interest, down that road lies a mistaken idea of freedom. It is a certain route to failure.

There’s something inherently striking about the title Mustang. It signifies something about the title girls, their free-spirits, billowing brown locks, continually running in a type of a herd, constantly full of life, movement, and motion. But with a mustang and any other creature full of life and vitality, there’s always an opposite force looking to impede, tame, and prod the spirit into some sort of submission. Because being free, being wild is constantly challenged in the world that we live in and this story is a prime example.

There’s something inherently striking about the title Mustang. It signifies something about the title girls, their free-spirits, billowing brown locks, continually running in a type of a herd, constantly full of life, movement, and motion. But with a mustang and any other creature full of life and vitality, there’s always an opposite force looking to impede, tame, and prod the spirit into some sort of submission. Because being free, being wild is constantly challenged in the world that we live in and this story is a prime example. “Nicole, you’re sleeping…”

“Nicole, you’re sleeping…” “Things are only as meaningful as the meaning that we allow them to have.” ~ Beverly

“Things are only as meaningful as the meaning that we allow them to have.” ~ Beverly

Where to start with Liberal Arts? It’s one of those deep blue funk movies. Zach Braff tackled this issue in Garden State, and Josh Radnor does a similar thing here. Because the reality is that we live in a generation of early onset midlife crises. In the opening moments, 35-year-old Jesse Fisher (Radnor) has nearly every article of clothing he has aside from the shirt off his back stolen from a local laundromat when his back is turned. We can easily surmise that this single event epitomizes his life right now, and this is hammered home rather obviously when his unnamed girlfriend clears her belongings out of his flat. There’s no better symbol of isolation and alienation than a break-up.

Where to start with Liberal Arts? It’s one of those deep blue funk movies. Zach Braff tackled this issue in Garden State, and Josh Radnor does a similar thing here. Because the reality is that we live in a generation of early onset midlife crises. In the opening moments, 35-year-old Jesse Fisher (Radnor) has nearly every article of clothing he has aside from the shirt off his back stolen from a local laundromat when his back is turned. We can easily surmise that this single event epitomizes his life right now, and this is hammered home rather obviously when his unnamed girlfriend clears her belongings out of his flat. There’s no better symbol of isolation and alienation than a break-up. It’s crucial to note that at this juncture nothing substantive builds between these two acquaintances romantically, but they do foster an immense connection. While Jesse is taken by Zibby’s personality, she, in turn, is discontent with a contemporary culture where no one dates–everybody’s casual about relationships. She feels unequivocally millennial and yet she readily admits these areas of old-fashionedness.

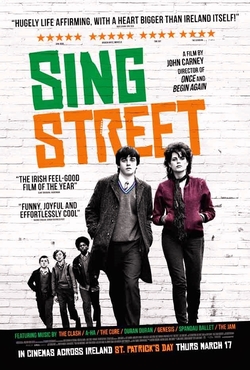

It’s crucial to note that at this juncture nothing substantive builds between these two acquaintances romantically, but they do foster an immense connection. While Jesse is taken by Zibby’s personality, she, in turn, is discontent with a contemporary culture where no one dates–everybody’s casual about relationships. She feels unequivocally millennial and yet she readily admits these areas of old-fashionedness. A famed philosopher of the MTV age once sang “video killed the radio star,” and John Carney’s Sing Street is a tribute to that unequivocal truth. Certainly, it’s what some might call a return to form for the director, landing closer to his previous work in Once, and staging the way for some wonderfully organic musical numbers set against the backdrop of Dublin circa 1985. In this respect, it’s another highly personal entry, and Carney does well to grab hold of the coming-of-age narrative.

A famed philosopher of the MTV age once sang “video killed the radio star,” and John Carney’s Sing Street is a tribute to that unequivocal truth. Certainly, it’s what some might call a return to form for the director, landing closer to his previous work in Once, and staging the way for some wonderfully organic musical numbers set against the backdrop of Dublin circa 1985. In this respect, it’s another highly personal entry, and Carney does well to grab hold of the coming-of-age narrative.