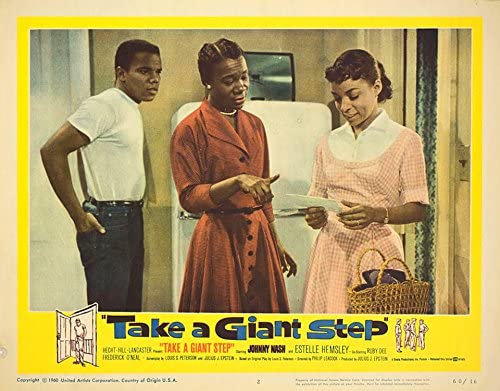

I know Ivan Dixon from Hogan’s Heroes and I’m hardly ashamed of that. He is a lifelong friend forged out of days poring over episodes on classic television stations. Whether he was satisfied with the work is an entirely different conversation, but I am thankful for what he brought to the ensemble in terms of humor and his reliable presence.

Then, recent viewings of Too Late Blues and A Raisin in The Sun, introduced Dixon into my life again in a renewed context. It was a new way to appreciate him even as I’ve become more aware of his prolific work behind the camera in more recent years.

However, in Nothing But a Man, he showcases a depth of character and a facet of the human experience, that frankly, was never accessible in a zany half-hour CBS comedy about American prisoners in a German Luftstalag or any of the smaller film roles he was bequeathed.

The images open with jackhammers as a gang of black section hands help lay down the railroad tracks. It’s hardly breezy work. In return for their sweat and middling conditions, they get a wage and a certain amount of freedom. In the evenings they can be found playing cards or frequenting the local beer parlors with “Heatwave” jamming away in the background. It’s lo-fi instant ambiance and Motown proves to be the perfect soundtrack for this film.

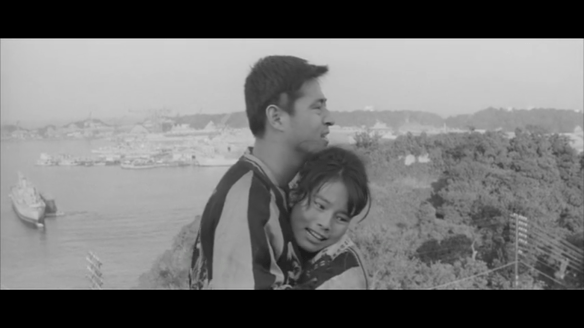

Although he’s not much of a churchgoer, Duff Anderson does show up at a local church meeting in Alabama for some food and southern hospitality. The girl dishing out the meal catches his eye. Josie Dawson (Abbey Lincoln) is the local teacher and the preacher’s daughter. This feels like an instant red flag. Anderson’s not exactly a moral saint, but he relishes her company.

There’s a modest kinship rapidly blooming between them. Even so, Nothing But a Man is a film that feels attentive to the thoughts and feelings of its characters spoken not simply through their words but the expressions on their faces and their actions. Dixon has such classically handsome features, and there’s something unequivocally lovely and unassuming about Abbie Lincoln’s smile. They bring the best out of each other as their romance strengthens.

However, there are other underlying issues to contend with. He has a young son, although he’s never been married before. The reverend looks at him with suspicion. He’s not the marrying kind. Even he knows it, but as a bastion of society, and a mediator between the black and white communities, Josie’s father is not welcoming of any disruption to his moral standing. It’s easy to feel for him even as the gravitational pull of empathy drags us in other directions.

Duff tells the preacher, “Us colored folks got a lotta churchgoing. It’s the white folks who need it real bad.” Of course, the irony of the words can’t be lost on us. Most if not all the white folks have their own churches to go to on Sunday, but it has no positive impact on their lives. I’m sure neither race has a total monopoly on this lukewarm reality. It’s human nature.

But there’s still another question to be answered: How did two Jewish men from up North hone in on such a resonating story of a black community, by taking New Jersey locales and fashioning them into the Deep South? It has to begin with this same kind of personal identification — some form of shared empathy — because they could not get close to the material any other way.

One thing that comes with watching films en masse is how they have the ability to inform one another. Take Pressure Point about a black psychiatrist treating a white neo-Nazi. He espouses vitriolic rhetoric about turning Blacks and Jews into the world’s scapegoats. He never uses the exact words, but it’s plain he believes them to be subhuman. I’m no expert, but it’s difficult for me to think of any group that has been more oppressed than these two.

However, this is not Stanley Kramer at work. It’s not a film about messages or social significance. Instead, we are allowed the privilege to walk alongside this man and woman, and even for a few moments become privy to their circumstances as depicted on screen.

It becomes apparent how the specter of racism dwells over every element of daily life. It cannot be conveniently compartmentalized or ignored because it always has a way of rearing its ugly head. White co-workers try and whip up “friendly” small-talk couched with subtle belittling and microaggressions. And you cannot have a quiet car ride without being accosted.

For whatever his negligible crimes against humanity might be, Duff is considered a troublemaker and standoffish. He won’t be cowed. The next stage in the systematic onslaught is bodily threats — he’s chastised mercilessly as a gas station attendant — only to be laid off out of fear of retaliation. And it doesn’t stop there as he’s totally blackballed and all the work propositions mysteriously dry up all around him. There is no deliverance from such a sphere of existence.

His primary problem is that he’s a proud man in an environment that is not ready to give him the respect he requires. What’s striking about Dixon’s portrayal is how it never feels combative or confrontational. That’s never his M.O., but he also will not degrade or ingratiate himself as a basic act of survival. There are some things that run deeper still, and he knows no other way than to be true to himself.

Self-proclaimed experts always talk about the problem with families is the lack of a father figure. But fathers need work and here you see the issue in its totality. It plays out throughout this movie. There’s hopelessness, then desperation, and a lashing out at all those close at hand — wives and children. However, while all this looks to be another portrait of dissolution and a man’s restlessness in a world that won’t let him be, it actually rings with a final note of hope.

I would never accuse Sidney Poitier of grandstanding, but there is a sense Dixon has the same substance as his peer, but this story feels even more mundane than the bulk of Poitier’s Hollywood work. The canvas and the drama are distilled to these very humble forms, and yet there is something powerful in these simple building blocks.

And if there is not a Hollywood happy ending, since this picture shuns everything that is expected by contemporary conventions, Duff does maintain his sense of human dignity. It’s all right there in the title. He was never asking much of others. Never looking for trouble. He just wants to be given the inalienable right to be a man.

For some, that’s easier than it is for others. Let us strive tirelessly for the day when all can claim that they really and truly are created equal. Nothing But a Man is a poignant reminder that this is still far from a reality.

I always knew Ivan Dixon was special, but I will never look at him the same way again. Abbey Lincoln also won a new fan today. I wish I had been aware of her career and her music sooner. But there’s no time like the present to rectify the situation. Let’s not live under the lie that says otherwise.

4.5/5 Stars