There’s something apropos about baseball having such a central spot in the storyline of Parenthood because this is a movie wrapped up in the American experience from a very particular era. Yes, the euphoric joys and manifold stressors of parenting are in some form universal, but Ron Howard’s ode to the art of childrearing is also wonderfully indicative of its time.

There’s something apropos about baseball having such a central spot in the storyline of Parenthood because this is a movie wrapped up in the American experience from a very particular era. Yes, the euphoric joys and manifold stressors of parenting are in some form universal, but Ron Howard’s ode to the art of childrearing is also wonderfully indicative of its time.

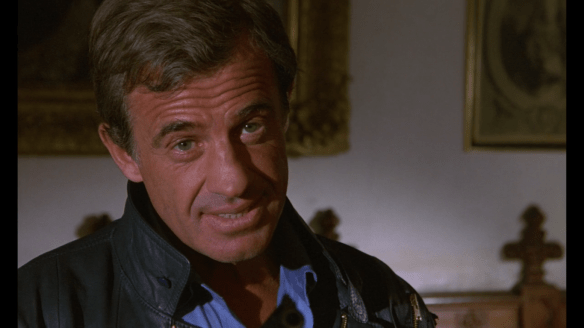

What is more relatable than wrangling the whole family to go to a ball game together? Gil (Steve Martin) and Helen (Mary Steenburgen) Buckman corral their family together, gathering all the stuff, and making sure the little ones don’t get run over by oncoming traffic as Randy Newman drawls his theme song. Piling into the family van and loading up to head home is a process unto itself. In one way, it’s a treat and an ordeal all rolled into one. A lot like parenting.

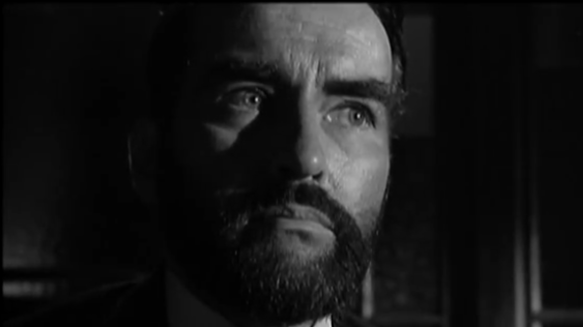

In fact, with its subject matter considered, this is not your prototypical Ron Howard movie, and by that I mean it feels more overtly personal in nature. Certainly, Clint Howard gets his usual cameo, but the story speaks more about experiences — experiences of the worries and the joys that overtake you.

They become a focal point of this story as the adults try to navigate life together with three kids and a large extended family. To a lesser degree, Little League baseball also becomes an integral part of life with Gil coaching his son Kevin’s team. It’s a different indicator of life as his boy is constantly made fearful of messing up.

He’s hardly the next Ozzie Smith or Ryne Sandberg. And when you’re a kid, the respect of your peers makes or breaks everything. You don’t want to be the one to let your team down. Could this all be part of the issues Kevin has according to his teachers?

However, as the roving ensemble is introduced with a patchwork of interrelated stories stitched together, you begin to appreciate the problems visible everywhere. This is imperative. They are part of what makes us human, and the full-bodied cast is what makes the relational dynamics sing.

Helen Buckman (Dianne Wiest) is a single mother just trying to get close to her kids with a distant son (Joaquin Phoenix) who won’t talk to her and a daughter (Martha Plimpton) who’s gone and got shacked up with a real airhead (Keanu Reeves). It’s like her life is crumbling all around her, and she must learn to hold it together, the best she knows how. This is her life.

Nathan Huffner (Rick Moranis) and his wife Susan (Harley Jane Kozak) are raising their daughter to be some sort of savant and her IQ runs circles around her cousins. She’s also simultaneously missing out on all the joys of being a kid. Her mother becomes overwhelmed by their strict parenting regimen, and it begins to leave a toll on their marriage. It’s so very easy to forget your priorities — how you ever fell in love in the first place.

Then, there’s the rather cantankerous Jason Robards. He’s fond of his youngest child Larry (Tom Hulce), the black sheep of the family because he’s lively and fun. Even dad is surprised when his boy returns home with a young son named Cool and a raging gambling problem; it’s got him in bad with some dangerous thugs.

Can you imagine the family dinners that these people have? There’s so much going on and yet they’re probably not all that far removed from our own family holidays. At least the spirit is there — something we can latch onto — and probably relate to.

However, it’s the party scenes allowing Steve Martin to showcase his comic chops as he takes on his cowboy persona to captivate all the kids and earn their appreciation while upholding his son’s reputation. It’s an emotional high in the bipolar ride you go through as a parent. Like any parents, they dream their little darlings will be valedictorians, and other times they fear that they might just as easily turn into a shooter. Often reality strikes a middle ground.

It’s far from flawless in its narrative, but that’s the point. It gets so bad Martin is going batty lashing out at his wife and everyone else. His son’s emotional anxieties have him worried. He’s stressed by a workplace that feels totally opportunistic and callous. Now, his wife’s supposed to have a baby and the news feels more like a burden than a gift.

If life doesn’t radically change, then perspectives certainly do. Robards and Martin have a surprisingly poignant conversation while sitting in the Little League dugout. Father talks to son about how there is no end zone in life. Your children and the people around you are there for good. And you’ll love them no matter what. It’s one significant moment of sentiment among many others.

In this way, Parenthood confidently modulates between drama and pathos, humor and romance, then circling back again. If little has changed from the beginning to end, then certainly their perspective evolves. It has something to do with embracing this beautiful chaos of life. Enjoying the ride as opposed to fearing every jolt of turbulence. Sometimes the simplest wisdom can be the most profound if you let it.

Grandma says she’s always appreciated the rollercoaster to going round and round on a merry-go-round. Parenthood is the rollercoaster and that’s a compliment. It feels alive and idiosyncratic in a way one does not usually attribute to Ron Howard’s more recent work. It’s a refreshing take and probably a high point of his directorial career. I am not a parent myself, but I can only imagine how its observations would take on new resonance after becoming one.

3.5/5 Stars