This is my entry in The Vive la France Blogathon. Thanks to Lady Eve and Silver Screen Modes for having me!

I recently read some excerpts out of Soren Kierkegaard’s “Attack on Christendom” and the Danish philosopher makes the case “Even when you don’t live by a Christian reality you live in a Christianized world. You know when you offend the collective consciousness.”

Although this context is changing in the present day, it very much fits the world of this film from Jean-Pierre Melville. There is this sense of propriety and a propensity toward specific ways and lifestyles as dictated by the prevailing cultural forces. In this case, the church. Though some choose to kick against the goads and challenge the status quo. That’s where our story commences.

The substantial backdrop of World War II also ties Leon Morin to Silence de la Mer (1949) and then Army of Shadows (1969), which came well after. Because, of course, before his days as the idol of the New Wave and a craftsman of pulp gangster classics, Melville actually worked as a member of a French Resistance himself. You cannot take part in something like that without it totally impacting how you perceive the world.

But there is still an important distinction to be made. This is hardly a war movie. Instead, the war serves as a background for the human experience — a human relationship between a man and a woman. Their relationship starts early in the occupation and stretches beyond the boundaries of V-E Day.

However, the terms seem very suggestive and in an unrefined exploration of the material this would be the case. Still, by some marvel, Melville manages to conduct an astute yet still spellbinding examination of spirituality. The woman: a militant communist. The man: a humble priest of a French parish.

It is two years after Hiroshima Mon Amour. Alain Resnais’s film is one of the most poetic meditations you will ever see on the likes of love, war, and memory. Leon Morin, Priest is certainly different. It is a different kind of cadence and rhythm developing its own sense of a world and the related themes to go with it. But it is supernally evocative in its own right.

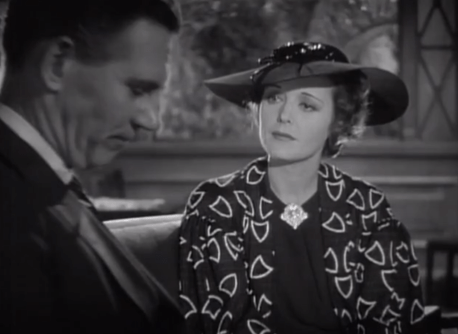

Emmanuelle Riva is Emmanuelle Riva, immaculately beautiful with eyes so bright they speak a language unto themselves. The moroseness is evident and yet they flit even momentarily between the cheery and the slightly provocative.

If Riva had her ascension on Hiroshima Mon Amour, Jean-Paul Belmondo was her equal as a nascent shooting star coming off of Godard’s Breathless. In this context, what a curious crossroads to descend upon Leon Morin, Priest. Such a quiet, tranquil picture seemingly more inclined toward the past than any manner of forward thinking. Neither is there a flashy, jazzy lifeblood to it.

However, in another sense, it could not be more fitting. Melville, as alluded to before, was the Godfather of many of the Nouvelle Vague talents — certainly Godard — and even if it’s only in particular instances, he still has a flair unto his own.

We might note a stripped-down peer like Robert Bresson as reference, but there are abrupt dashes of pizzazz here that feel like the youth of the New Wave, whether in an implied slap to the face or a jarring jump in continuity. The persistent use of fade-outs allows the passage of time to be conceived at a leisurely pace.

The city is such an extraordinary space brimming with character imbued by the sheer amount of years being lived in its midst. At first, the shroud of war is almost a comical distraction. In its early days, solemnity has not set in. Then, the feathered garb of the Italians gives way to the no-nonsense domed blitzkrieg of the Germans.

Families have their children baptized to conveniently hide their Jewish lineage from any prying eyes within the incumbent authorities. Because soon enough, they start deporting undesirables en force. Paranoia and anti-semitism set in, even within our heroine Barny’s own workplace. Fugitives seeking asylum call on her charity in need of ration stamps and a place to gather themselves on their road to freedom.

Then, one afternoon she resolves to give a local priest a piece of her mind during confessions. She settles on the name Leon Morin as he seems like he might be the most receptive party given the peasantry pedigree of his moniker. If we were to label this decision we might label it as nothing short of Providence.

On first impression, Jean-Paul Belmondo feels like an unconventional casting for a member of the cloth. I often allude to his coming out of the tradition of Bogart but could Bogey have played a priest? Hardly. Still, Belmondo pulls it off with a candor, still blunt and true in its implementation. Because he cares deeply for others nevertheless, aided by his plain features and pragmatic perspective which both suit him well.

His dour space with only a desk, a window, and a shelf of books prove a very inviting place. Because he is such a person. At first an unassuming but ultimately charismatic spiritual leader. His lending library is open to Bardy and she begins to visit him and read his books. Somehow battling her urges to doubt due to curiosity and her own desire to gravitate toward him.

She is adamant about scientific proof for God and we begin an interim period that feels like it might be a precursor to Rohmer’s dialogues from My Night at Maud’s. In subsequent days, all the girls start coming to call on the young priest. Whether it’s merely physical attraction or some other ethereal quality about him is never stated outright. This cynical viewer is reminded of the glib aphorism, “flirt to convert.” And yet with each visitor, he comes ready to share the hope that is within him.

Bardy’s assured coworker Marion is one caller and then another very attractive girl who plans to seduce him; it seems she’s in the business of it with a laundry list of conquests going before her. And yet the perplexing aspect of the priest is how impregnable he is even as he welcomes each woman in, cultivates their spiritual well-being, and deals with them in such a frank manner.

Likewise, from the pulpit, he does not spare his words for the congregation sitting before him any given holy day. Recalling much of what Kierkegaard criticized, he warns them not to be merely “Sunday Christians.” “Not living out a Christian life drives away the undecided” and this is nothing new.

Hypocrisy or closer still being little different from everyone else is often one of the greatest faults of people who are deemed “Christian.” He further extolls them, “They should each be an apostle in their own setting.” It is a fallacy that only a priest can do the work of God. So while he speaks with consternation, he wraps it up with a note of hope. Because according to him, there is “A God whose grace is given to the heretics and believers alike, loved equally in his sight.”

We see even momentarily his guiding force. Why he pursued Barny and did his best to shepherd her. He’s no elitist. His time and services are extended to all people. He lives it out in the day-to-day of life together with others.

When Barny and Morin must finally say goodbye there is so much in the air, gratefulness, sadness, wistfulness — even as she has fallen in love for his righteous guidance and he remains resolved in his mission to tend after the souls of those in his stead.

To merely say this is a conversion story is too simplistic. To claim it’s suggesting the sensuality of forbidden love is off the mark. We already confirmed it is not a war picture. The brilliance of Melville is painting around these conventional lines with the utmost nuance. Of course, the performances are superb. The two cinematic saints in Riva and Belmondo make it possible. The fact we are fallen humans, ripe with warring desires and doubts, make it necessary. Dealing with spirituality in such a perceptive manner is nothing short of a modern miracle.

4.5/5 Stars

Note: Bogart actually did portray a priest in The Left Hand of God toward the end of his career. Thanks for those who pointed it out to me. Much appreciated!

The Pre-Code era of Hollywood is a legitimate marvel because in a span of only a few solitary years was a period of filmmaking bursting at the seams with vice, corruption, and licentiousness that we would never see again until the late 1960s.

The Pre-Code era of Hollywood is a legitimate marvel because in a span of only a few solitary years was a period of filmmaking bursting at the seams with vice, corruption, and licentiousness that we would never see again until the late 1960s.

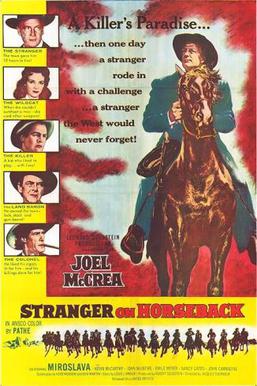

I didn’t know my Grandpa too well because he passed away when I was fairly young but I always remembered hearing that he really enjoyed reading Louis L’Amour. It’s not much but a telling statement nonetheless. I’ve read and seen Hondo (1953), which stars John Wayne and Geraldine Fitzgerald, and yet I’d readily proclaim Stranger on Horseback the finest movie adaptation of an L’Amour novel.

I didn’t know my Grandpa too well because he passed away when I was fairly young but I always remembered hearing that he really enjoyed reading Louis L’Amour. It’s not much but a telling statement nonetheless. I’ve read and seen Hondo (1953), which stars John Wayne and Geraldine Fitzgerald, and yet I’d readily proclaim Stranger on Horseback the finest movie adaptation of an L’Amour novel.