Though the image quality of the print I saw hardly stands the test of time, there’s something almost modern about The Virginian’s characterizations or at least what it deems interesting to show.

Though the image quality of the print I saw hardly stands the test of time, there’s something almost modern about The Virginian’s characterizations or at least what it deems interesting to show.

There’s actually a layering of tones and a fluctuation in the moral dilemma at its core that feel a great deal more nuanced than a cut-and-dry shoot ’em up western beholden to the stereotypes that the genre was founded on.

In Victor Fleming’s hands, The Virginian was not only a western but an early talkie extending the possibilities of the medium. It’s true that at this point there was a lot of pioneering still to do in film as there had been in the West.

One aspect this picture took advantage of in particular was exterior shooting which gives the West an almost palpable nature because we see the dust swirling up from the feet of the cattle, we hear the constant chorus of animal sounds, and the expanse of the prairie is daunting but also starkly majestic.

Beyond genre conventions, it’s indubitably a seminal picture since we get the overwhelming sense that we are seeing a persona coming into his own — the crystallized image of stalwart Americana — Gary Cooper. Although he was a minor star and this was not only his first starring role in a western but also his first talkie, soon enough he would be one of the most beloved actors of his day.

True, he also made many pictures outside the genre of considerable repute in their own right, and yet there’s no underselling how important the western was in further instilling Cooper’s legacy for generations of faithful fans. His eponymous character in The Virginian is an early marker of the mythology of western masculinity that would stretch all the way to High Noon (1952) and Man of the West (1958). In fact, at times this picture, featuring an imminent showdown, looks eerily similar to its future brethren from two decades later.

His cattle foreman character is a man’s man. He’s a plain-speaking, straight-talking man of few words (Yes ma’am, No ma’am), who nevertheless cares deeply about honor and personal integrity. Yet he still gives off the homely qualities of a man of the West. And it’s true that much of this film adaptation of Owen Wister’s novel and subsequent play is concerned with the butting of heads that comes with the clashing cultures between West and East.

On one side you have the Virginian and the rest of the townsfolk and on the other is the new schoolmarm, Molly Stark Wood (Mary Brian), who causes quite a stir among the men in town and is a welcomed bit of civility to everyone else.

There is a sense that she can help tame this uncivilized world that lacks manners, education, and law and order. The themes would crop again and again most notably in Ford’s own moody rumination The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962). But here there’s an oddly good-natured comedy streak. It’s not all horse opera.

The Virginian and his old pal Steve have a fine time switching the babies about to be christened by the parson which causes quite the hubbub. But the two men also jockey for the new gal’s affection in all matter of things. Looking to carry her bags or get a dance with her at the community gathering.

The Virginian and Molly even conduct a discourse on Romeo and Juliet which proves to be an enlightening distillation of their two differing perspectives. All of this is fine and dandy. Even the swapping of infants like a pair of regular cow rustlers feels innocent enough. But there’s another side of this world as well.

The main antagonist named Trampas (Walter Huston) wears black and yet he’s more of a cunning thief than an ornery devil, all guns a blazing. He’s more apt to shoot a man in the back when he’s not looking like a coward than actually face him man to man.

He also happens to be a cattle rustler himself and he’s pulled Steve in with him because it’s a pretty easy business. Lots of reward for little risk. Except if and when you get caught there are no two ways about it. The law of the land says you’ll be strung up even if you’re a friend.

And so The Virginian doesn’t shy away from the harsher realities of this lifestyle whether it be hangings or the prevalence of gun duels. It’s a part of the life but also so at odds with what is considered respectable in other parts of the world. Thus, not only the schoolmarm, but the audience, and really everyone else involved must grapple with what is right and what is wrong and how we reconcile those perceived differences.

4/5 Stars

“When you call me that, smile!” – The Virginian

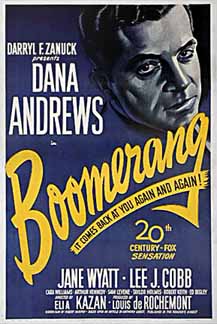

Boomerang shares some similarities to

Boomerang shares some similarities to