What’s striking about Alfred Hitchcock is the sheer breadth of his work and how his career managed to take him in so many directions as he continued to evolve and experiment with his craft from silent pictures, to talkies, then Hollywood, and all the way into the modern blockbuster age. And yet the very expansiveness of his oeuvre begs the question, where to begin with it all? Certainly, his lineup of masterpieces in the 1950s are a must.

What’s striking about Alfred Hitchcock is the sheer breadth of his work and how his career managed to take him in so many directions as he continued to evolve and experiment with his craft from silent pictures, to talkies, then Hollywood, and all the way into the modern blockbuster age. And yet the very expansiveness of his oeuvre begs the question, where to begin with it all? Certainly, his lineup of masterpieces in the 1950s are a must.

But of his early silent pictures, The Lodger is the film that Hitchcock himself noted was really the beginning of his filmography as we know it and within its frames, there are some telling signs of an artist coming to grips with his craft.

His subject matter here is a bit of a Jack the Ripper-type tale set in London. A rash of murders has overtaken the town as coincidentally a new tenant with suspicious tendencies moves into the room of a local family. Their daughter does her best to make him feel welcome but her macho boyfriend, a member of the local police force, is skeptical of the competition. Especially since circumstance seems to point to the lodger’s guilt. So in this central conflict, we have a bit of the innocent man motif that Hitch would scrutinize and continue to tweak again and again.

Hitchcock already shows an immense aptitude for visual experimentation, utilizing his mise en scene in fascinating ways. He makes great use of staircases whether he only shows a man’s hand as it slides along the banister or he sets up crucial moments along the expanses of the stairwell, characters slowly descending toward us being representative of innumerable tension.

We also unwittingly have one of Hitch’s first documented cameos and his assistant director on the picture is none other than his soon-to-be wife and lifelong collaborator, Alma Reville. That connection alone makes this production crucial to Hitchcock’s future career.

It’s easy to make the assertion that Hitchcock remained in the most basic sense a silent filmmaker his entire career and if we can count F.W. Murnau as one of his major influences from his time in Germany, you have that same sense of visuals over dialogue or even title cards. Some of his greatest scenes are in fact nearly silent. The crop dusting chase in North by Northwest (1959) or Norman Bates discarding the evidence in Psycho (1960) both spring to mind.

Though the parameters set up by the studio and expectations of his audience meant his leading man could not be found to be guilty, Hitch still manages to make the scenario as interesting as he possibly could — even if the degree of moral ambiguity wasn’t quite to his liking.

Consequently, in many ways, The Lodger also manages to be one of Hitchcock’s most tenderly romantic films. Because while his pictures have romance and passion they are more often than not subverted by the macabre, sensuality, or that notable dry wit. But here, the love story seems generally sincere.

Because there are tinges of true heartbreak here and the circumstances that bring the two lovers together are imbued with emotional consequence. Even the intricacies of a flashback and genuine interactions between two people who exude a certain chemistry make up for any overly theatrical moments courtesy of the tenderhearted heartthrob Ivor Novello.

But as he generally had a knack for doing Hitchcock also knows how to squeeze the most out of his ending sequences with the most satisfying spectacle. In this case, although the police have exonerated their suspect, the mob is after him and he flees them only to get caught on the iron works of a fence, his handcuffs leaving him dangling, vulnerable to the onslaught of humanity. He hangs there pitifully, at their mercy, a near Christ-like figure.

Perhaps the outcome was not quite what he wanted but the burgeoning master still manages a true Hitchcockian ending worthy of remembrance alongside some of his more championed pictures.

3.5/5 Stars

“Blessed are the poor in spirit for their’s is the kingdom of heaven”

“Blessed are the poor in spirit for their’s is the kingdom of heaven” Again, I must confess that I have not read yet another revered American Classic. I have not read A Farewell to Arms…But from the admittedly minor things I know about Hemingway’s prose and general tone, this film adaptation is certainly not a perfectly faithful translation of its source material. Not by any stretch of the imagination.

Again, I must confess that I have not read yet another revered American Classic. I have not read A Farewell to Arms…But from the admittedly minor things I know about Hemingway’s prose and general tone, this film adaptation is certainly not a perfectly faithful translation of its source material. Not by any stretch of the imagination. I wrote an

I wrote an  Are you always drawn to the loveless and unfriended? ~ Edward Rochester

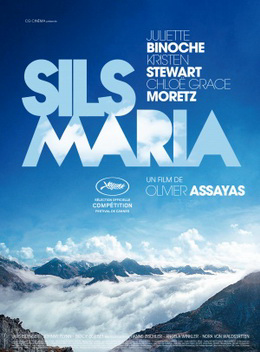

Are you always drawn to the loveless and unfriended? ~ Edward Rochester It’s my prerogative to respect films that dare to leave me questioning their ambitions and their outcomes. Clouds of Sils Maria is such a film. At times it gets so caught up in its own meta-narrative perhaps too much so.

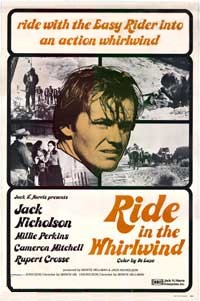

It’s my prerogative to respect films that dare to leave me questioning their ambitions and their outcomes. Clouds of Sils Maria is such a film. At times it gets so caught up in its own meta-narrative perhaps too much so. Anyone who takes the time to search out this movie whether the reason is a young Jack Nicholson who wrote, helped finance, and starred in this western or because it’s directed by cult favorite Monte Hellman, they probably already know it was shot consecutively with The Shooting. Whereas the first western has an unnerving existential tilt as the plot takes us through an endless journey across the oppressive desert plains, you could make the claim that Ride in the Whirlwind is a more conventional western.

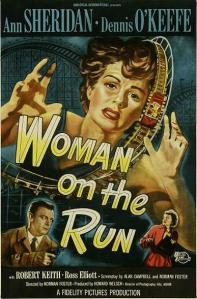

Anyone who takes the time to search out this movie whether the reason is a young Jack Nicholson who wrote, helped finance, and starred in this western or because it’s directed by cult favorite Monte Hellman, they probably already know it was shot consecutively with The Shooting. Whereas the first western has an unnerving existential tilt as the plot takes us through an endless journey across the oppressive desert plains, you could make the claim that Ride in the Whirlwind is a more conventional western. B-films have little time to waste and this one jumps right into the action. In a matter of moments, a man is shot, another man has killed him and a third witness gets away into the night. Although Frank Johnson (Ross Elliot) is rounded up by the police to be a witness he gives them the slip for an undisclosed reason and they must spend every waking hour trying to track him down.

B-films have little time to waste and this one jumps right into the action. In a matter of moments, a man is shot, another man has killed him and a third witness gets away into the night. Although Frank Johnson (Ross Elliot) is rounded up by the police to be a witness he gives them the slip for an undisclosed reason and they must spend every waking hour trying to track him down. The opening credits roll and recognition comes with each name that pops on the screen. Jean Arthur, James Stewart, Claude Rains, Edward Arnold, Guy Kibbee, Thomas Mitchell, Eugene Palette, Beulah Bondi, H.B. Warner, Harry Carey, Porter Hall, Charles Lane, William Demarest, Jack Carson, and of course, Frank Capra himself.

The opening credits roll and recognition comes with each name that pops on the screen. Jean Arthur, James Stewart, Claude Rains, Edward Arnold, Guy Kibbee, Thomas Mitchell, Eugene Palette, Beulah Bondi, H.B. Warner, Harry Carey, Porter Hall, Charles Lane, William Demarest, Jack Carson, and of course, Frank Capra himself. “He could never fit in with our distorted viewpoint, because he’s honest, and sincere, and good. If that man’s crazy, Your Honor, the rest of us belong in straitjackets!” ~ Jean Arthur as Babe Bennett

“He could never fit in with our distorted viewpoint, because he’s honest, and sincere, and good. If that man’s crazy, Your Honor, the rest of us belong in straitjackets!” ~ Jean Arthur as Babe Bennett