Although Hitchcock did many riffs off the same themes, he very rarely tried to do the same film twice over. The Man Who Knew Too Much might be the one exception and even then if you place these two thrillers from 1934 and 1956 up next to each other, they’re similarities are fairly nominal.

Although Hitchcock did many riffs off the same themes, he very rarely tried to do the same film twice over. The Man Who Knew Too Much might be the one exception and even then if you place these two thrillers from 1934 and 1956 up next to each other, they’re similarities are fairly nominal.

The bare-bones plot involving international espionage, a pair of unassuming parents, and the kidnapping of their child remains the same. But most everything else is drastically different.

Thus, it becomes an interesting exercise in juxtaposition. It really depends on what the viewer deems definitive in a quality film mixed with personal preference. Without question, this initial offering from a younger director is grittier and less made up but it’s subsequently a less technical sound achievement with also little score to speak of. We trade out James Stewart and Doris Day’s singing for the less remembered pair of Leslie Banks and Edna Best. But nevertheless, this version of The Man Who Knew Too Much is an enjoyable international adventure crossing the globe from the Swiss Alps to England.

The Lawrences are on a lively vacation complete with skiing and skeet shooting with their precocious daughter (Nova Pilbeam) but after an acquaintance winds up murdered, the family finds themselves embroiled in a treacherous world of espionage. The dead Frenchmen left them a message to pass on to his contact but that knowledge finds them deeply distressed when their daughter is kidnapped. From that point, the intentions of the story are fairly straightforward. It’s simply a matter of watching Hitchcock at work.

Peter Lorre fresh off his emigration from Nazi Germany in the wake of Hitler, ironically plays the quintessential international menace, cigarette curled between his lips. It was so recent in fact that the man who made a name for himself as slimy undesirables learned all his lines phonetically because he still had yet to gain full command of the English language. But thank goodness we had him for this film and many to come. He perennially made movies more interesting by his mere presence. That marvelous face of his is one in a million.

There are some wonderful sequences and typical touches of Hitchcockian style and subversion, namely a sun-worshipping cult hiding out in a cathedral but, overall, it’s not always a cohesive exhibition in suspense. His greatest achievements always seem to fit together seamlessly to the perfect crescendo like a thrilling piece of clockwork. Whereas sometimes it feels as if a few of these scenes are strung together.

But that does not take away from some of the better set pieces namely Hitchcock’s original Royal Albert Hall sequence and a different finale altogether with a final shootout that is still harrowing in its own right. And of course, the foreboding clangs of Peter Lorre’s pocket watch leave their mark on this film just as his eerie whistling became his foretoken in Lang’s M (1931). Hitch would only continue to fine tune his formula but there’s no question that The Man Who Knew Too Much is a diverting thriller and the first in a lineup of six consecutive successes from the director during the 1930s.

3.5/5 Stars

In the 1970s political paranoia involved issues in the realm of Watergate. Government conspiracy and that type of thing perfectly embodied by some of Alan Pakula’s best films. But it’s important to realize in order to better understand this particular thriller, the 1980s were a decade fraught with fears of Soviet infiltration compromising our national security. The Cold War was still a part of the public consciousness even after being a part of life for such a long time already. So No Way Out has a bit of Pakula’s apprehension in government and maybe even a bit of the showmanship of Psycho with some truly jarring twists.

In the 1970s political paranoia involved issues in the realm of Watergate. Government conspiracy and that type of thing perfectly embodied by some of Alan Pakula’s best films. But it’s important to realize in order to better understand this particular thriller, the 1980s were a decade fraught with fears of Soviet infiltration compromising our national security. The Cold War was still a part of the public consciousness even after being a part of life for such a long time already. So No Way Out has a bit of Pakula’s apprehension in government and maybe even a bit of the showmanship of Psycho with some truly jarring twists.

n the last decade or so arguably the greatest action/spy/thriller franchises have been Jason Bourne, James Bond, and Mission Impossible. To their credit, each series has crafted several passable films fortified by a few real stalwarts of the spy thriller genre. Although many of these series thrive on gadgetry, set pieces, and a cynical tone more at home in the modern millennium, one thing that set some of the better films apart were interesting female characters.

n the last decade or so arguably the greatest action/spy/thriller franchises have been Jason Bourne, James Bond, and Mission Impossible. To their credit, each series has crafted several passable films fortified by a few real stalwarts of the spy thriller genre. Although many of these series thrive on gadgetry, set pieces, and a cynical tone more at home in the modern millennium, one thing that set some of the better films apart were interesting female characters. Body Snatchers works seamlessly and efficiently on multiple fronts, both as science fiction and social commentary. Don Siegel helms this film with his typical dynamic ease putting every minute of running time to good use. The screenwriter, Daniel Manwaring, put together perhaps one of the greatest political allegories ever penned and, on the whole, it’s a taut thriller combining sci-fi and horror to a tee.

Body Snatchers works seamlessly and efficiently on multiple fronts, both as science fiction and social commentary. Don Siegel helms this film with his typical dynamic ease putting every minute of running time to good use. The screenwriter, Daniel Manwaring, put together perhaps one of the greatest political allegories ever penned and, on the whole, it’s a taut thriller combining sci-fi and horror to a tee. You couldn’t hope to come up with a better story than this. Pure movie fodder if there ever was and the most astounding thing is that it was essentially fact — spawned from a William Goldman script tirelessly culled from testimonials and the eponymous source material. All the President’s Men opens at the Watergate Hotel, where the most cataclysmic scandal of all time begins to split at the seams.

You couldn’t hope to come up with a better story than this. Pure movie fodder if there ever was and the most astounding thing is that it was essentially fact — spawned from a William Goldman script tirelessly culled from testimonials and the eponymous source material. All the President’s Men opens at the Watergate Hotel, where the most cataclysmic scandal of all time begins to split at the seams. But it only takes a few breakthroughs to make the story stick. The first comes from a reticent bookkeeper (Jane Alexander) and like so many others she’s conflicted, but she’s finally willing to divulge a few valuable pieces of information. And as cryptic as everything is, Woodward and Bernstein use their investigative chops to pick up the pieces.

But it only takes a few breakthroughs to make the story stick. The first comes from a reticent bookkeeper (Jane Alexander) and like so many others she’s conflicted, but she’s finally willing to divulge a few valuable pieces of information. And as cryptic as everything is, Woodward and Bernstein use their investigative chops to pick up the pieces. Gordon Willis’s work behind the camera adds a great amount of depth to crucial scenes most notably when Woodward enters his fateful phone conversation with Kenneth H. Dahlberg. All he’s doing is talking on the telephone, but in a shot rather like an inverse of his famed Godfather opening, Willis uses one long zoom shot — slow and methodical — to highlight the build-up of the sequence. It’s hardly noticeable, but it only helps to heighten the impact.

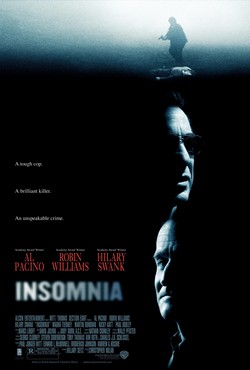

Gordon Willis’s work behind the camera adds a great amount of depth to crucial scenes most notably when Woodward enters his fateful phone conversation with Kenneth H. Dahlberg. All he’s doing is talking on the telephone, but in a shot rather like an inverse of his famed Godfather opening, Willis uses one long zoom shot — slow and methodical — to highlight the build-up of the sequence. It’s hardly noticeable, but it only helps to heighten the impact. “You and I share a secret. We know how easy it is to kill somebody.” – Robin Williams as Walter Finch

“You and I share a secret. We know how easy it is to kill somebody.” – Robin Williams as Walter Finch Inspired directors oftentimes do not make themselves known in grandiose flourishes but in the smallest of touches, and in his debut, Polish newcomer Roman Polanski does something interesting with the opening of Knife in the Water. Perhaps it’s not that unusual, but it’s also hard to remember the last film where the camera was on the outside of a driving car, looking in. We see shadows of faces overlaid with credits and then finally the faces are revealed only to be shrouded by the reflections of overhanging trees glancing off the windshield.

Inspired directors oftentimes do not make themselves known in grandiose flourishes but in the smallest of touches, and in his debut, Polish newcomer Roman Polanski does something interesting with the opening of Knife in the Water. Perhaps it’s not that unusual, but it’s also hard to remember the last film where the camera was on the outside of a driving car, looking in. We see shadows of faces overlaid with credits and then finally the faces are revealed only to be shrouded by the reflections of overhanging trees glancing off the windshield. Thus, it becomes an exercise of technical skill, much like Hitchcock in Lifeboat or any other film that limits itself to a single plane of existence. Polanski’s framing of his shots with one figure right on the edge of the frame and others arranged behind is invariably interesting. Because although space is limited, it challenges him to think outside the box, and he gives us some beautiful overhead images as well which make for a generally dynamic composition. That is overlaid by a jazzy score of accompaniment courtesy of Krzysztof Komeda, a future collaborator on many of Polanski’s subsequent works during the ’60s.

Thus, it becomes an exercise of technical skill, much like Hitchcock in Lifeboat or any other film that limits itself to a single plane of existence. Polanski’s framing of his shots with one figure right on the edge of the frame and others arranged behind is invariably interesting. Because although space is limited, it challenges him to think outside the box, and he gives us some beautiful overhead images as well which make for a generally dynamic composition. That is overlaid by a jazzy score of accompaniment courtesy of Krzysztof Komeda, a future collaborator on many of Polanski’s subsequent works during the ’60s. However, at this point, as a young director, he is simply sharpening his teeth and getting acclimated to the genre a little bit. Knife in the Water builds around the three sides of a love triangle, creating a dynamic of sexual tension because that’s what tight quarters and jealousy do to people. This is less of a spoiler and more of a general observation, but the film does not have a major dramatic twist. Instead, there are heightened tensions, a bit of underwater deception, and finally a fork in the road.

However, at this point, as a young director, he is simply sharpening his teeth and getting acclimated to the genre a little bit. Knife in the Water builds around the three sides of a love triangle, creating a dynamic of sexual tension because that’s what tight quarters and jealousy do to people. This is less of a spoiler and more of a general observation, but the film does not have a major dramatic twist. Instead, there are heightened tensions, a bit of underwater deception, and finally a fork in the road. Adapted from the John le Carré novel, this is a black & white spy thriller that personifies cold war paranoia in ways that Bond never could. Richard Burton is an operative working in Berlin before being demoted to a librarian job. It looks like our narrative is heading in a direction hardly fit for a spy film. Its intentions are not so obvious at first, and it keeps its audience working for the rest of the film.

Adapted from the John le Carré novel, this is a black & white spy thriller that personifies cold war paranoia in ways that Bond never could. Richard Burton is an operative working in Berlin before being demoted to a librarian job. It looks like our narrative is heading in a direction hardly fit for a spy film. Its intentions are not so obvious at first, and it keeps its audience working for the rest of the film.