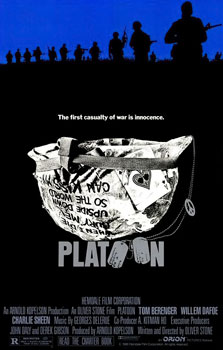

It’s a rather interesting parallel that Charlie Sheen is playing much the same role his father did in Apocalypse Now. At least in the sense that they become our entry point into the mire of war, specifically in Vietnam. But where Apocalypse seemed to belong more so to Brando or even Duvall, Platoon is really Willem Dafoe’s film. At least he’s the one who makes it what it is. His final moment is emblematic of the entire narrative.

It’s a rather interesting parallel that Charlie Sheen is playing much the same role his father did in Apocalypse Now. At least in the sense that they become our entry point into the mire of war, specifically in Vietnam. But where Apocalypse seemed to belong more so to Brando or even Duvall, Platoon is really Willem Dafoe’s film. At least he’s the one who makes it what it is. His final moment is emblematic of the entire narrative.

But it is also striking that the film opens with an excerpt from Ecclesiastes as follows, “Rejoice young man in your youth…” But the latter half of that same verse has major implications that will come into play later.

For now, these soldiers muddle their way through their tours of duty the best they can. Smoke, beer, and Smokey Robinson is the perfect way to combat the insanity and humidity right outside your tent.

Oliver Stone conjures up themes of politics and government conspiracies. The first word is uttered several times throughout Platoon but in the general sense. When you get a group of people together vying for positions and attention there’s bound to be politics. As for government conspiracy, Stone doesn’t quite scrape that barrel, although to be sure as a Vietnam veteran himself perhaps he has a lot to be disgruntled about.

Instead, he has a cast of characters who get to reflect all the angst and disillusionment for him and it’s a fairly impressive bunch. Aside from Sheen and Dafoe, John Bergener, Keith David, John McGinley, Forrest Whitaker, and even Johnny Depp make appearance wading their way through Vietnam.

It’s been far too long since I’ve seen Apocalypse Now to draw too many comparisons. However, although Platoon is a perturbing film it’s not the same type of expansive labyrinth that I recall from Coppola’s epic. Charlie Sheen’s voiceovers attempt to add an introspective tinge to the entire narrative, but that is not where the strength of the film lies.

Platoon also has its share of pyrotechnics, in fact, it succumbs to them too often but that’s not the reason the film is affecting either. It’s the aftermath of those explosions. The carnage that is left in the wake of the barrages of RPGs. The bodies maimed and the images that haunt these young men.

And as audience members, it’s hard not to feel something. Repulsed. Angry. Frustrated. Confused. Perhaps that is the film working — giving even a zenith of the taste of what it was to be in the jungles of Vietnam back in 1967. This is one of those experiences I cannot take too often because it’s almost too much.

My initial hope was that Stone would not inject this film with his own brand or message and I will say that when I watch Platoon I am not left with the feeling that I am listening to Oliver Stone but instead I am watching something terribly volatile unfold. That’s certainly a testament to this film. In the end, Platoon is bolstered by its sheer intensity.

But back to Ecclesiastes, the earlier verse ends “and let your heart be pleasant during the days of young manhood. And follow the impulses of your heart and the desires of your eyes. Yet know that God will bring you to judgment for all these things.” And it’s this final bit that is important in suggesting that young men are laid low due to their joy. But it’s hard to make that type of assertion. If anything, a film such as Platoon is perplexing because the answers are unclear and the reasons the world works the ways it does are not known to us.

Young men will continue to walk through life naively and he will struggle through life questioning the presence of God as much as this seemingly apathetic indifference towards the suffering in the world. Whether Stone was grappling with those same questions is up for contention but the beauty of film is that it very rarely works on a singular level. It can mean many things to many people. So it is with Platoon.

4/5 Stars

WWII is always a fascinating touchstone of history because it has some many intricate facets extending from the Pacific to the European Theater to the American Home Front and so on, each bringing with it unique stories of everyday individuals doing extraordinary things. One of the best-kept secrets is the 442nd Infantry Division later joined with the 100th and effectively making the first all Japanese-American fighting unit which served over in Italy and France.

WWII is always a fascinating touchstone of history because it has some many intricate facets extending from the Pacific to the European Theater to the American Home Front and so on, each bringing with it unique stories of everyday individuals doing extraordinary things. One of the best-kept secrets is the 442nd Infantry Division later joined with the 100th and effectively making the first all Japanese-American fighting unit which served over in Italy and France. It’s the bane of my literary existence, but I must admit that I have never read Joseph Heller’s seminal novel Catch-22. Please refrain from berating me right now, perhaps deservedly so, because at least I have acknowledged my ignorance. True, I can only take Mike Nichol’s adaptation at face value, but given this film, that still seems worthwhile. I’m not condoning my own failures, but this satirical anti-war film does have two feet to stand on.

It’s the bane of my literary existence, but I must admit that I have never read Joseph Heller’s seminal novel Catch-22. Please refrain from berating me right now, perhaps deservedly so, because at least I have acknowledged my ignorance. True, I can only take Mike Nichol’s adaptation at face value, but given this film, that still seems worthwhile. I’m not condoning my own failures, but this satirical anti-war film does have two feet to stand on. The Chaplain (Anthony Perkins) doesn’t feel like a man of the cloth at all, but a nervously subservient trying to carry out his duties. An agitated laundry officer (Bob Newhart) gets arbitrarily promoted to Squadron Commander, and he ducks out whenever duty calls. Finally, the Chief Surgeon (Jack Gilford) has no power to get Yossarian sent home because as he explains, Yossarian “would be crazy to fly more missions and sane if he didn’t, but if he was sane he’d have to fly them. If he flew them he was crazy and didn’t have to; but if he didn’t, he was sane and had to.” This is the mind-bending logic at the core of Catch-22, and it continues to manifest itself over and over again until it is simply too much. It’s a vicious cycle you can never beat.

The Chaplain (Anthony Perkins) doesn’t feel like a man of the cloth at all, but a nervously subservient trying to carry out his duties. An agitated laundry officer (Bob Newhart) gets arbitrarily promoted to Squadron Commander, and he ducks out whenever duty calls. Finally, the Chief Surgeon (Jack Gilford) has no power to get Yossarian sent home because as he explains, Yossarian “would be crazy to fly more missions and sane if he didn’t, but if he was sane he’d have to fly them. If he flew them he was crazy and didn’t have to; but if he didn’t, he was sane and had to.” This is the mind-bending logic at the core of Catch-22, and it continues to manifest itself over and over again until it is simply too much. It’s a vicious cycle you can never beat. But the tonal shift of Catch-22 is important to note because while it can remain absurdly funny for some time, there is a point of no return. Yossarian constantly relives the moments he watched his young comrade die, and Nately (Art Garfunkel) ends up being killed by his own side. It’s a haunting turn and by the second half, the film is almost hollow. But we are left with one giant aerial shot that quickly pulls away from a flailing Yossarian as he tries to feebly escape this insanity in a flimsy lifeboat headed for Sweden. It’s the final exclamation point in this farcical tale.

But the tonal shift of Catch-22 is important to note because while it can remain absurdly funny for some time, there is a point of no return. Yossarian constantly relives the moments he watched his young comrade die, and Nately (Art Garfunkel) ends up being killed by his own side. It’s a haunting turn and by the second half, the film is almost hollow. But we are left with one giant aerial shot that quickly pulls away from a flailing Yossarian as he tries to feebly escape this insanity in a flimsy lifeboat headed for Sweden. It’s the final exclamation point in this farcical tale. We’re used to getting our hands dirty in the thick of World War II, whether it is in the European theater or the Pacific, but very rarely do we consider the consequences that come in the wake of such an earth-shattering event. Things do not end just like that. There must be periods of rebuilding and rehabilitation. There is unrest and upheaval as the world continues to groan in response.

We’re used to getting our hands dirty in the thick of World War II, whether it is in the European theater or the Pacific, but very rarely do we consider the consequences that come in the wake of such an earth-shattering event. Things do not end just like that. There must be periods of rebuilding and rehabilitation. There is unrest and upheaval as the world continues to groan in response. There are love scenes that are quiet, subdued, and truly intimate. In fact, it feels rather like Hiroshima Mon Amour where the camera lingers so closely on two figures in such close proximity. There does not have to be great movement or dramatic interludes because having two people next to each other should be enough. The historical context in itself seems to be enough. For that film, it meant Japan post-1945. For this one, it’s Poland after the clouds of war have lifted.

There are love scenes that are quiet, subdued, and truly intimate. In fact, it feels rather like Hiroshima Mon Amour where the camera lingers so closely on two figures in such close proximity. There does not have to be great movement or dramatic interludes because having two people next to each other should be enough. The historical context in itself seems to be enough. For that film, it meant Japan post-1945. For this one, it’s Poland after the clouds of war have lifted.

There are also strategic vignettes sprinkled throughout to boost morale and the camaraderie between allies. A few Brits can be heard taking part in the gaiety and making friends with our protagonists. A table of Hispanic soldiers takes in a floor show. One of our hostesses gets a moving letter from her older brother in the marines who is bent on returning to his family and proving that his training can outlast any “Jap” out there. There’s a last-minute marriage ceremony that we are privy to. Sam Jaffe introduces the audience to a few Russian allies, an Australian soldier has just returned from the front, and several Chinese air cadets get a rousing appreciation. Merle Oberon (the only actress close to being Asian in the film) gives them a stirring sendoff. Finally,

There are also strategic vignettes sprinkled throughout to boost morale and the camaraderie between allies. A few Brits can be heard taking part in the gaiety and making friends with our protagonists. A table of Hispanic soldiers takes in a floor show. One of our hostesses gets a moving letter from her older brother in the marines who is bent on returning to his family and proving that his training can outlast any “Jap” out there. There’s a last-minute marriage ceremony that we are privy to. Sam Jaffe introduces the audience to a few Russian allies, an Australian soldier has just returned from the front, and several Chinese air cadets get a rousing appreciation. Merle Oberon (the only actress close to being Asian in the film) gives them a stirring sendoff. Finally,  “What a fouled-up outfit I got myself into” – Sgt. Zack

“What a fouled-up outfit I got myself into” – Sgt. Zack But the old WWII vet simply acknowledges the facts and retorts with his own piece of trivia. In the all Japanese-American regiment the 442nd 3,000 Nisei “idiots” got the purple heart for bravery. All he knows is that he’s an American no matter how he’s treated. That doesn’t change. Once more Fuller delivers some of the most engaging portrayals of Asian characters ever and the discussions of race relations were way ahead of their time. Both Richard Loo and James Edwards are honorable characters who hardly fall into any common stereotype.

But the old WWII vet simply acknowledges the facts and retorts with his own piece of trivia. In the all Japanese-American regiment the 442nd 3,000 Nisei “idiots” got the purple heart for bravery. All he knows is that he’s an American no matter how he’s treated. That doesn’t change. Once more Fuller delivers some of the most engaging portrayals of Asian characters ever and the discussions of race relations were way ahead of their time. Both Richard Loo and James Edwards are honorable characters who hardly fall into any common stereotype.

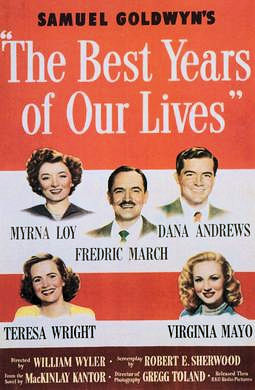

Inherent in a film with this title, much like It’s a Wonderful Life, is the assumption that it is a generally joyous tale full of family, life, liberty, and the general pursuit of happiness. With both films you would be partially correct with such an unsolicited presumption, except for all those things to be true, there must be a counterpoint to that.

Inherent in a film with this title, much like It’s a Wonderful Life, is the assumption that it is a generally joyous tale full of family, life, liberty, and the general pursuit of happiness. With both films you would be partially correct with such an unsolicited presumption, except for all those things to be true, there must be a counterpoint to that.