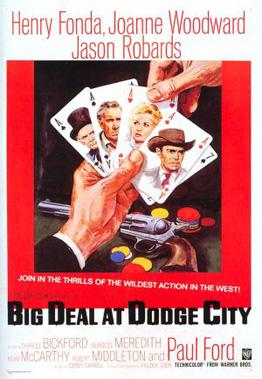

A Big Hand for The Little Lady is not something we see anymore: It’s a big, sprawling western brimming with comedy and a dash of intrigue. There’s a romping score from David Raksin and a frenzied opening as we watch the assembling of our secondary stars. And they are quite formidable from the grizzled Charles Bickford, Kevin McCarthy as a rapscallion with a glint in his eye, and the always irascible Jason Robards. They’re coming together, not for a showdown or a hanging, but for something far more momentous: a once-a-year poker game with astronomical stakes.

A Big Hand for The Little Lady is not something we see anymore: It’s a big, sprawling western brimming with comedy and a dash of intrigue. There’s a romping score from David Raksin and a frenzied opening as we watch the assembling of our secondary stars. And they are quite formidable from the grizzled Charles Bickford, Kevin McCarthy as a rapscallion with a glint in his eye, and the always irascible Jason Robards. They’re coming together, not for a showdown or a hanging, but for something far more momentous: a once-a-year poker game with astronomical stakes.

It’s mostly a contained western within the town and not just within the town, but within the local hotel and the backroom where only the richest and wealthiest are allowed a seat at the table. There’s little doubt that they could hold down a movie themselves, but they feel more like the entrée than the primary attraction.

For a time as an audience we are kept outside just wondering what’s happening between these rarefied few and then Henry Fonda, Joanne Woodward, and their son enter the scene.

Coming out as it did in 1966, A Big Hand for The Little Lady is one of those films that so easily melds with the TV age because it feels like a family movie and it was something that came of age originally on the stage courtesy of Fielder Cook.

What sets it apart as a movie are these stars, and they dole out. Fonda is his late period affable self and all his roles come off so seamlessly. Joanne Woodward may have been superseded finally by her super star husband Paul Newman, but this picture is a fine reminder of what a jubilant talent she was.

They come into town on their way to 40 acres of farm. They need some repairs on their wagon and they look to spend the night before heading on their way. It’s simple enough. Bu there must always be complications. Meredith (Fonda) proves himself to be a reformed gambler, but the temptation of a poker game is too great for him.

Kevin McCarthy has eyes for his radiant wife or sees a walking stooge before him. For whatever reason he vouches for the man and allows him in despite the remonstrations of his compatriots. They’re not accustomed to such interruptions to their yearly ritual.

Based on the facts that rules have never been bent for anyone, all of this feels like a very unprecedented development — not to mention a compromising of the rules. But Fonda goes to his hotel room to retrieve some of their life savings to front the $1,000 needed to just sit at the table.

What follows is a bizarre even absurd scenario as Fonda gets in too deep with all their funds, and he’s not left with enough collateral to stay in the game. They’ve bullied him out even as he has a killer hand of cards.

He proceeds to keel over on the spot into the loving arms of his wife, only for her to take up his mantle at the poker table as he gets attention from the local doc (Burgess Meredith). This, again, is highly irregular. They look down their noses at womenfolk, especially ones who have never played before.

After she learns the general premise of the game, she vows to put it on hold as she speaks with the bank manager. They go traipsing to the bank single file to meet Mr. Ballinger (Paul Ford), another irregular turn. While he won’t initially give her any help, once seeing her hand (another dubious red flag), he agrees to back her. What follows next is not something that needs writing about.

I’m not much for playing poker, but as a narrative device it’s one of my favorites because there’s always two levels to the game. It provides a concrete reason for a varied assortment of characters to sit down together — The Odd Couple is a favorite example — and there are usually stakes of another kind too.

However, here the movie almost feels like it reaches a premature climax with Joanne Woodward carrying a sway with the men that she hardly has time to build since most of the minutes beforehand she was away watching their wagon.

The film’s saving grace is it’s final abrupt revelation — I’m not sure if there are warning signs of any kind — but it’s a twist nonetheless. It’s also difficult not to see how Woodward’s acumen presages Paul Newman’s first-class showing and antics trying to agitate Robert Shaw in cards during The Sting.

The beauty of this movie is how it gives the actress the reins, and she proves herself to be the consummate performer. What’s more the cast is loaded with old pros who all seem game for a good time.

3/5 Stars