Even a man who is pure in heart, and says his prayers by night; May become a wolf when the wolfbane blooms and the autumn moon is bright.

Even a man who is pure in heart, and says his prayers by night; May become a wolf when the wolfbane blooms and the autumn moon is bright.

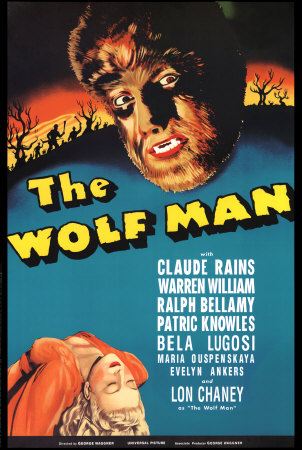

Universal had an impressive catalogue of horror films during the 30s and 40s that integrated gothic and science fiction themes into stories such as Frankenstein, Dracula, and The Invisible Man. The Wolf Man can be considered part of that same dynasty and it established Lon Chaney Jr. much like Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi before him, as a horror film staple. He was the Wolf Man as Karloff was Frankenstein’s Monster and Lugosi was Dracula. That’s how it worked.

What makes many of these films compelling is how they take myth and ground it in a believable reality. Fact and fiction becomes homogenized in a sense and such a world is a wonderful place to draw out horror. Because it can be supernatural, otherwordly, and frightening but it also hits close to home since there is a shred of truth always visible.

In this case, the film opens with the prodigal son, the lumbering, good-natured Larry Talbot (Lon Chaney Jr.) returning to the estate of his well to do father Sir John (Claude Rains). There’s some mention of a dead brother and a hunting accident–some tragic events. This is what brought Larry home and he seems to have patched things up well enough with his dad. As they say, time heals all wounds and it’s easy enough to dismiss it with that.

Anyways, life seems generally good. He’s getting acclimated with the quaint town of Lianwilly and he conveniently spies a girl working in her father’s shop across the way, the pretty ingenue Gwen Conliffe (Evelyn Ankers) who happens to be already engaged. But that doesn’t stop her from wanting to spend time with him because he really is a giant teddy bear with nary a violent bone in his body.

This is the preexisting world that the story develops only to be thrown off its axis by a telling event. It’s the origin of Larry’s troubles and they begin with a visit to a gypsy caravan, ending with him incurring a bite from a killer wolf. But the implications are much more ominous and deep-seated than that.

Because the trauma begins to eat away at him and his father though the local doctor sees his change of state as merely a psychological issue. Something he can be cured of. He’s only misguided–a little wrong in the head. They fail to see the full manifestations of his new sickness which transform him and lead him off into the night seeking after victims.

But if The Wolfman was simply an excuse to see a beast, it’s hard to gather that the film would have resonated with anyone then or now. In fact, this film is very much comparable to the superhero films we are so accustomed to now. The great installments are made that way by compelling characters and solid storytelling.

Curt Siodmak the brother of famed film noir director Robert Siodmak must be commended on his script which in a mere 70 minutes develops a streamlined story line full of a certain moodiness. To his credit, he helped lay the foundation for a whole legend that has become the standard archetype for any narratives involving werewolves.

The very fact the little poem uttered throughout the film is practically omnipresent, conjured up by so many individuals, works as a fitting harbinger of things to come. Meanwhile, the gypsies played by (Bela Lugosi) in an unfortunately relegated role and Maria Ouspenska, while pigeon-holed takes on the role of mystical soothsayers with ease. Throw in silver bullets, silver-headed walking sticks, and pentagrams and you have all the necessary touchstones (except full moons). Apparently that comes later.

Furthermore, the general atmosphere, time lapse effects, and painstaking makeup work of Jack Pierce all contribute to the heady brew. Perhaps because it is precisely these things that will make some disdain the horror genre with scorn that actually imbue a B-picture such as this a surprisingly engaging aura. It’s very much a part of the mythology that has been built around these monster movies and while meeting our expectations in a sense, that’s only a small, albeit integral part of this story.

Because, everything must ultimately return back to Lon Chaney’s performance as the genial giant Larry Talbot. He’s the complete antithesis of a monster. It’s not what he wants to be and he proves to have such a strong capacity for love. He keeps short accounts and he has a tremendous urge to protect others from harm. It’s innate in him. That’s what makes his ghastly transformation so devastating. Literally no one sees it coming (except Maleva) and you can attribute that to pure ignorance or you could go out on a limb and say it’s because Larry comes off as a genuinely good human being. By the film’s conclusion we feel truly sorry for him and that’s the key

But if we dare take the metaphor further still, I suppose we could say that his curse was a physical manifestation–reflecting the animalistic evil that can be inside of any person. The stuff that’s churning inside of our being at any given time. That cauldron of dark desires bubbling up. That’s what makes the dividing line between the physical and psychological so interesting in The Wolf Man. Normally they exist in separate spheres but in some ways this film makes them one in the same.

4/5 Stars

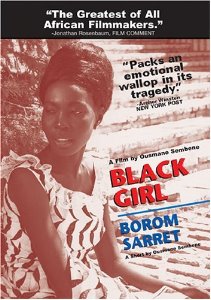

What’s fascinating about this film is how it manages to give voice to those who are normally silenced and even in her subservience this narrative powerfully lends agency to a young Senegalese woman’s perspective. Because even when she is silent and words are not coming out of her mouth and her status ultimately makes her powerless, the very fact that her mind is constantly thinking, her eyes observing and so on mean something. Inherently there’s a great empowerment found there even if it’s only known by her and seen by the outside observer peering into her life. That’s part of her. We are given a view into what she sees. We can begin to understand her helplessness and isolation. Where she came from and the life she left behind. Giving up the master narrative of the entitled and shown the flip side of the world for once.

What’s fascinating about this film is how it manages to give voice to those who are normally silenced and even in her subservience this narrative powerfully lends agency to a young Senegalese woman’s perspective. Because even when she is silent and words are not coming out of her mouth and her status ultimately makes her powerless, the very fact that her mind is constantly thinking, her eyes observing and so on mean something. Inherently there’s a great empowerment found there even if it’s only known by her and seen by the outside observer peering into her life. That’s part of her. We are given a view into what she sees. We can begin to understand her helplessness and isolation. Where she came from and the life she left behind. Giving up the master narrative of the entitled and shown the flip side of the world for once. Prior to the making and release of Monsieur Verdoux Charlie Chaplin had undoubtedly hit the most turbulent patch in his historic career and not even he could come out of scandal and political upheaval unscathed. To put it lightly his stock in the United States plummeted.

Prior to the making and release of Monsieur Verdoux Charlie Chaplin had undoubtedly hit the most turbulent patch in his historic career and not even he could come out of scandal and political upheaval unscathed. To put it lightly his stock in the United States plummeted. The glamour of limelight, from which age must pass as youth centers

The glamour of limelight, from which age must pass as youth centers  But now no one’s there. The seats are empty, the aisles quiet, and he sits with a dazed look in his flat the only recourse but to go back to bed. It’s as if the poster on the wall reading Calvero – Tramp Comedian is paying a bit of homage to his own legend but also the very reality of his waning, or at the very least, scandalized stardom. It adds insult to injury.

But now no one’s there. The seats are empty, the aisles quiet, and he sits with a dazed look in his flat the only recourse but to go back to bed. It’s as if the poster on the wall reading Calvero – Tramp Comedian is paying a bit of homage to his own legend but also the very reality of his waning, or at the very least, scandalized stardom. It adds insult to injury. It’s important to know that he writes off such an assertion as nonsense and one can question whether this is Chaplin’s chance at revisionist history or more so an affirmation of his life’s actual trajectory–working through his current reality that the world questions (IE. Marrying a woman much younger than himself in Oona O’Neil who he nevertheless dearly loved).

It’s important to know that he writes off such an assertion as nonsense and one can question whether this is Chaplin’s chance at revisionist history or more so an affirmation of his life’s actual trajectory–working through his current reality that the world questions (IE. Marrying a woman much younger than himself in Oona O’Neil who he nevertheless dearly loved).

There might be an initial predilection to call The Soft Skin Francois Truffaut’s most conventional film to date, but for me, it shows at this fairly early point in his career he seems to have grasped the main tenets of traditional filmmaking. Because his first films are full of life, energy, and idiosyncratic verve that easily charm their audience but here we see a film that in most ways looks like other classic works, well constructed and still quite engaging. Because within this very framework Truffaut is able to play around with issues that in themselves are still quite compelling. Love, intimacy, infidelity, and the like. Even with familiar names like Truffaut and Raoul Coutard, it feels very un-Nouvelle Vague. And that’s okay.

There might be an initial predilection to call The Soft Skin Francois Truffaut’s most conventional film to date, but for me, it shows at this fairly early point in his career he seems to have grasped the main tenets of traditional filmmaking. Because his first films are full of life, energy, and idiosyncratic verve that easily charm their audience but here we see a film that in most ways looks like other classic works, well constructed and still quite engaging. Because within this very framework Truffaut is able to play around with issues that in themselves are still quite compelling. Love, intimacy, infidelity, and the like. Even with familiar names like Truffaut and Raoul Coutard, it feels very un-Nouvelle Vague. And that’s okay. Blanche Dubois and Stanley Kowalski. They’re both so iconic not simply in the lore of cinema history but literature and American culture in general. It’s difficult to know exactly what to do with them. Stanley Kowalski the archetypical chauvinistic beast. Driven by anger, prone to abuse, and a mega slob in a bulging t-shirt who also happens to be a hardline adherent to the Napoleonic Codes. But then there’s Blanche, the fragile, flittering, self-conscious southern belle driven to the brink of insanity by her own efforts to maintain her epicurean facade. They’re larger than life figures.

Blanche Dubois and Stanley Kowalski. They’re both so iconic not simply in the lore of cinema history but literature and American culture in general. It’s difficult to know exactly what to do with them. Stanley Kowalski the archetypical chauvinistic beast. Driven by anger, prone to abuse, and a mega slob in a bulging t-shirt who also happens to be a hardline adherent to the Napoleonic Codes. But then there’s Blanche, the fragile, flittering, self-conscious southern belle driven to the brink of insanity by her own efforts to maintain her epicurean facade. They’re larger than life figures. Cat People has one of those sensationalized B-picture premises and there are moments when its meager aspects let slip that this is a low-budget effort, but within those restrictions, it moves with a certain purpose and chilliness. It’s true that producer Val Lewton had a B-movie renaissance going on at RKO Studios and Cat People is one of his treasures.

Cat People has one of those sensationalized B-picture premises and there are moments when its meager aspects let slip that this is a low-budget effort, but within those restrictions, it moves with a certain purpose and chilliness. It’s true that producer Val Lewton had a B-movie renaissance going on at RKO Studios and Cat People is one of his treasures. At Oliver’s work, talk around the water cooler is made compelling in that his best pal and colleague is the sensible Alice (Jane Alexander) always ready to lend a listening ear. She’s genuine in accepting Irena for who she is because she can tell that Oliver earnestly loves her. But at the same time, she serves as a contrasting figure — someone who is completely different than this enigmatic creature.

At Oliver’s work, talk around the water cooler is made compelling in that his best pal and colleague is the sensible Alice (Jane Alexander) always ready to lend a listening ear. She’s genuine in accepting Irena for who she is because she can tell that Oliver earnestly loves her. But at the same time, she serves as a contrasting figure — someone who is completely different than this enigmatic creature. Themla & Louise hardly feels like typical Ridley Scott fare but then again, neither is this a typical movie. It pulls from numerous genres that have been depicted countless times before from buddy movies to caper comedies, road films, and the like. But perhaps the intrigue begins with the two leads.

Themla & Louise hardly feels like typical Ridley Scott fare but then again, neither is this a typical movie. It pulls from numerous genres that have been depicted countless times before from buddy movies to caper comedies, road films, and the like. But perhaps the intrigue begins with the two leads. The last time I saw Hoosiers it was on VHS and I was only a boy and I hardly remember anything. Gene Hackman yelling. Dennis Hopper as a drunk. Jimmy the boy wonder, “The Picket Fence”, and of course Indiana basketball at its finest. But in those opening moments, as he drives into town and walks through the halls of his new home, I realized just how much I miss Gene Hackman. Yes, he’s still with us but the moment he decided to step out of the limelight and retire from his illustrious career as an actor, films got a little less exciting. His passionate often fiery charisma is dearly missed.

The last time I saw Hoosiers it was on VHS and I was only a boy and I hardly remember anything. Gene Hackman yelling. Dennis Hopper as a drunk. Jimmy the boy wonder, “The Picket Fence”, and of course Indiana basketball at its finest. But in those opening moments, as he drives into town and walks through the halls of his new home, I realized just how much I miss Gene Hackman. Yes, he’s still with us but the moment he decided to step out of the limelight and retire from his illustrious career as an actor, films got a little less exciting. His passionate often fiery charisma is dearly missed.