Yasujiro Ozu has the esteem of being christened “The Most Japanese Filmmaker.” It’s certainly a high honor, but at first, it can feel rather counter-intuitive because after all, such a great master of cinema cannot be considered average or a composite in the scheme of Japanese film history. And I don’t think that is what this title is trying to get at. The fact is that Ozu, over time, really experimented with the conventions written by classical western filmmakers and he built his own unique aesthetic that is quite evident later in his career. That being said, his film’s are very Japanese in the way they interact with and dissect the culture that he comes out of, and I think that is paramount to understanding and ultimately appreciating his work.

Yasujiro Ozu has the esteem of being christened “The Most Japanese Filmmaker.” It’s certainly a high honor, but at first, it can feel rather counter-intuitive because after all, such a great master of cinema cannot be considered average or a composite in the scheme of Japanese film history. And I don’t think that is what this title is trying to get at. The fact is that Ozu, over time, really experimented with the conventions written by classical western filmmakers and he built his own unique aesthetic that is quite evident later in his career. That being said, his film’s are very Japanese in the way they interact with and dissect the culture that he comes out of, and I think that is paramount to understanding and ultimately appreciating his work.

It’s no different with Late Autumn, Ozu’s penultimate film, a social-familial drama that shares a great deal of similarity to some of his earlier work. The fact is, he’s constantly returning to these ideas of marriage, family, generational differences, and the underlying etiquette that is so prevalent in Japan and Asian cultures in general. But of course, much of what he examines is universal and that’s what allows his films to remain timeless.

With Late Autumn, in particular, it’s easy to marvel at how the director frames his space because he seems to have tremendous spatial recognition. He’s confident in his aesthetics which he highlights with colors and axis lines, which are then further embellished with human subjects. Not many directors are brazen enough to show us an empty room, a hallway, or the mundane facade of a building, but Ozu is so self-assured in his composition. They are too long and occur too often to be establishing shots. He wants to continually convey to us the space that his characters inhabit and he’s meticulous. Everything is placed with pinpoint precision just the way he wants. And it shows.

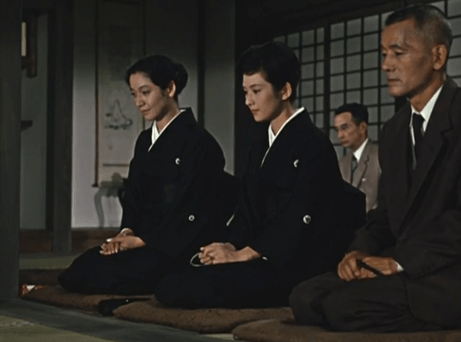

On a basic level, Late Autumn can meld nicely with many of the director’s other works also based around the seasons. In this color installment, three adult men gather for the funeral of one of their mutual childhood friends. It’s a sad occasion as they wistfully remember the good old days when they were young and in love. But as a service to their deceased friend, they agree to find a husband for his sweet sunshine-faced daughter Ayako (Yoko Tsukasa). However, they also worry for his widower Akiko (Setsuko Hara), who is equally beautiful, since the years have been very good to her. What follows is the typical fumbling attempts at matchmaking, trading manners, and so on. When Mr. Mamiya inquires if he should ask for a young man’s picture and resume, we assume it’s a joke, but he’s quite serious.

What makes Autumn different than earlier classics like Late Spring or even Tokyo Story, is that it shows the next generation of young people. The kids embrace the rockability of Elvis while reading Mickey Mouse cartoons. The young adults are folks who have grown up in the specter of WWII. They want to leave behind the world of useless honor and restraint.They speak their minds and show their discontent.

I enjoy the light touches of humor injected into this film because the three chums sit around the bar making observations with a bouncy score that seems more at home in a Tati comedy. Sometimes they’re genuinely trying to be funny, but more often it’s hilarious because they’re actually so dysfunctional. They take on this task of watching over their friend’s family with all seriousness, but they get sidetracked by their own desires and personal concerns. They stir up rumors, make waves, and ultimately cause a lot of trouble. Everything gets muddled and it’s the blunt and frank assertions of young Yuriko (Mariko Okada) that points out their failures. She sees how they have made a mess of things and calls them out for it. Perhaps it feels abrasive, but I think they like her for it and the audience does as well. She’s a reflection of this new generation that’s not looking to mince words or hide behind social etiquette. They’re fed up with that type of lifestyle. In fact, Yuriko is the one who says marriage is the worst. The ideal would be if love and marriage always went together, but they don’t.

I enjoy the light touches of humor injected into this film because the three chums sit around the bar making observations with a bouncy score that seems more at home in a Tati comedy. Sometimes they’re genuinely trying to be funny, but more often it’s hilarious because they’re actually so dysfunctional. They take on this task of watching over their friend’s family with all seriousness, but they get sidetracked by their own desires and personal concerns. They stir up rumors, make waves, and ultimately cause a lot of trouble. Everything gets muddled and it’s the blunt and frank assertions of young Yuriko (Mariko Okada) that points out their failures. She sees how they have made a mess of things and calls them out for it. Perhaps it feels abrasive, but I think they like her for it and the audience does as well. She’s a reflection of this new generation that’s not looking to mince words or hide behind social etiquette. They’re fed up with that type of lifestyle. In fact, Yuriko is the one who says marriage is the worst. The ideal would be if love and marriage always went together, but they don’t.

Thus, although the relationship between Ayako and her mother takes center stage as the film progresses, Yuriko is extremely pivotal. It’s the lives of the first two women that are affected by the unintentional bungling of these men, but it is Yuriko, who signifies change for the better. In many ways, this story feels very similar to Late Spring in particular, but the interest is not so much in original ideas as it is in re-imagining ideas. It’s a film for the 1960s where men are slowly losing their vice-like grip and societal norms are changing as women move to the forefront. But what remains are the suggestion that it’s alright to push back against societal pressures, and interpersonal relationships are delicate flowers that must be cultivated with care. So easily they can be trampled and destroyed. It takes a certain type of person to acknowledge their own faults while persistently loving those around them.

Thus, although the relationship between Ayako and her mother takes center stage as the film progresses, Yuriko is extremely pivotal. It’s the lives of the first two women that are affected by the unintentional bungling of these men, but it is Yuriko, who signifies change for the better. In many ways, this story feels very similar to Late Spring in particular, but the interest is not so much in original ideas as it is in re-imagining ideas. It’s a film for the 1960s where men are slowly losing their vice-like grip and societal norms are changing as women move to the forefront. But what remains are the suggestion that it’s alright to push back against societal pressures, and interpersonal relationships are delicate flowers that must be cultivated with care. So easily they can be trampled and destroyed. It takes a certain type of person to acknowledge their own faults while persistently loving those around them.

This is the utmost compliment, but in many ways, Setsuko Hara reminds me a great deal of my own grandmother, a woman who radiated a genuine kindness that was apparent to everyone who walked through life alongside her. Bless their souls. Both of them.

4.5/5 Stars

Disney is, by now, a gargantuan media empire of parks, merchandise, and movie magic. It’s easy to forget that there were days when the studio was in desperate need of a hit. 101 Dalmatians proved to be just what the vet ordered.

Disney is, by now, a gargantuan media empire of parks, merchandise, and movie magic. It’s easy to forget that there were days when the studio was in desperate need of a hit. 101 Dalmatians proved to be just what the vet ordered. Supposedly Robert Altman’s inspiration for 3 Women came from a dream he had, as with many of the most original ideas out there. Admittedly, in some ways, the resulting project feels like his rendition of a European art-film. It has some roots in Bergman and Polanski while transposing the action to his usual locales that are inbred into the fabric of America — places like the California deserts and Texas.

Supposedly Robert Altman’s inspiration for 3 Women came from a dream he had, as with many of the most original ideas out there. Admittedly, in some ways, the resulting project feels like his rendition of a European art-film. It has some roots in Bergman and Polanski while transposing the action to his usual locales that are inbred into the fabric of America — places like the California deserts and Texas. There’s not a mean bone in Ronald Colman’s body. He’s the perfect gentleman and Greer Garson is his perfect counterpart. Theirs is the story of Paula Ridgeway and Smithy, or Charles Rainier and Margaret Hanson, or closer yet, both of these stories together. But there’s need for some explanation.

There’s not a mean bone in Ronald Colman’s body. He’s the perfect gentleman and Greer Garson is his perfect counterpart. Theirs is the story of Paula Ridgeway and Smithy, or Charles Rainier and Margaret Hanson, or closer yet, both of these stories together. But there’s need for some explanation.