The world of blue-collar workers is immediately spelled out through a visual shorthand of hard hats, bulldozers, and oil rigs. At the center of Carole Eastman’s story is Bobby (Jack Nicholson) a young man who works alongside his buddy Elton and lives with his sometime girlfriend Rayette (Karen Black).

She’s pretty and nice enough, but there’s a sense Bobby feels like she’s somehow beneath him. Sure, she’s not the smartest girl — working as a local waitress — but she means well and seeks love like any normal human being. Still, it’s the kind of lifestyle perfectly summarized by the sounds of Tammy Wynette singing about heartbreak, songs like D-I-V-O-R-C-E, and the like.

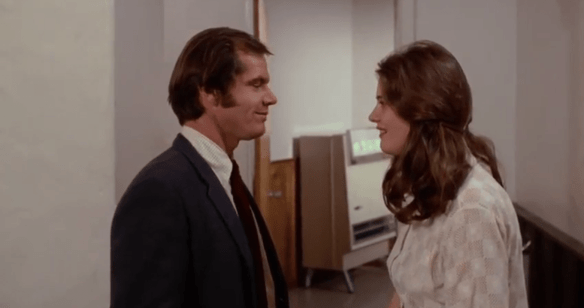

Upon closer observation, it would appear Jack Nicholson is entering his prime — his snide, derisive years — as a seminal antihero of New Hollywood. The only difference, here he’s found in the bowling alley playing a round with his friends. He comes off as a jerk berating his girlfriend for being such a crummy player. So she can’t bowl, but Bobby makes it personal, bringing her to tears. It’s indicative of the toxic cycles that they go through together. He belittles her, pushes her away, and then asks her to come back. He’s never willing to commit. Never able to say I love you. And yet he can’t be without her.

The first third of the movie is mostly about slotting his character. Soon we learn a little more about him. His sister (Lois Smith) is a classically trained pianist. In fact, it runs in their family. Bobby was a bit of a prodigy himself, though he turned his back on the family obsession. Now he learns his father is dying. He doesn’t want to see him — it’s easy enough to tell — because they weren’t exactly on pleasant terms, but the supplications of his sister have an effect and he acquiesces.

The arc of the story is simple and Bob Rafelson’s picture is built out of the framework of the performances more than anything else. I think this is what I missed the first time I watched Five Easy Pieces. I was waiting for something to happen when all the time it was happening right in front of me.

Bobby’s prepared to go it alone and at the very last minute reconciles with Rayette yet again so they head up together. They also pick up a pair of lady hitchhikers making their way up to Alaska because it’s a destination not full of crap like everywhere else. They bemoan a pessimistic world full of maggots and riots; Bobby doesn’t want to hear it because he’s a bit of a misanthrope himself. He takes no pleasure in the trip he is making and they’re not helping.

Again, the prevailing mood of the picture is this kind of rustic, blue-collar atmosphere exemplified by that Tammy Wynette soundtrack and the bowling alley milieu. It plays as the complete antithesis of classical music on the piano and the family’s cozy residence tucked away in idyllic Washington state. It’s the music and change in scenery acting as the main signifier of Bobby’s quaintly middle-class upbringing. Tammy might be great in her own right, but she’s not exactly Mozart or Beethoven.

When Bobby makes his fateful return, he finds his father now is catatonic and looked after by a burly caregiver. His brother Carl (Ralph Waite) is a loquacious eccentric who walks like a duck and wears a neck brace after a recent injury. Parita (Smith) is the most likable but still a creature of this insular and totally pretentious ecosystem. She doesn’t know any better.

It might say more about my own affinities rather than any fault of this film, but I never feel any amount of investment or emotional exchange going on. However, this is exactly the point. We understand the drudgery Bobby associates with his familial life and everything it entails. It’s better to be poor and free than to be trapped by expectations and crowded by pompous self-entitled armchair analysts trying to outdo one another.

Bobby at the same time is self-conscious of Rayette and protective of her because, in her own unadorned, simple manner, she’s a whole lot more real than any of these other imposters. At first, he puts her up in a hotel, and then she shows up unannounced willfully chafing against the propriety around her simply by being herself.

There is one person who does captivate Bobby. It’s his brother’s wife-to-be, another pianist named Catherine (Susan Anspach). The attraction between them is evident though he cannot figure out how she is so contented with the life he has run away from. In observing his condition, she notes he’s a person with no love for himself, no respect for himself, no love of friends, family, work. It strikes a little too close as he strives listlessly after some semblance of happiness.

I will say that Jack’s scene with his father, now crippled and silenced by a stroke, makes me appreciate his individual talents as a performer on their own merit. It’s not about any amount of trickery or charisma as much as we are privy to his acting process. We see him at work evoking a brokenness and a transparency of character I don’t often attribute to him.

Here he is before us laying it bear and crying out. It’s a release if not a total resolution. The film’s ending is another telling evolution in his ongoing saga of discontentment. We watch him as he ditches his car, his girl, his coat, and grabs a ride on a big rig up north. The destination is uncertain. Could it be Canada maybe Alaska? It doesn’t really matter.

What we do know is that he’s incorrigible, and yet it’s only a symptom of a broader problem. I’m can’t personally speak to whether this is true, but there is a sense Bobby is indicative of a broader social enigma. An entire generation of people lost and searching for something in the landscape of the 1970s — the dawn of a new decade — and still weighed down by the baggage of the past. This isn’t a new phenomenon and it’s universal. Because we realize over 50 years later there’s still something relatable by this unabating restlessness.

4/5 Stars