My knowledge of silent cinema is admittedly littered with blindspots. Some of this must be attributed to the sheer number of shorts the era engendered and also the number of extant films which will remain lost if not for some secret cache hidden away in someone’s perfectly insulated basement. The rest falls on pure ignorance.

If you’re like me, you might know Chaplin, then you turn to Keaton, and finally Lloyd. It was famed writer James Agee who might have well propagated this lineage to later viewers when it came to the silent clowns who formed the bedrock for the forthcoming film industry. And it’s true everyone seems to be indebted to these fellows on some account. But the one who rarely gets a mention in the same breath is Harry Langdon and I’ve done this as much as anyone else.

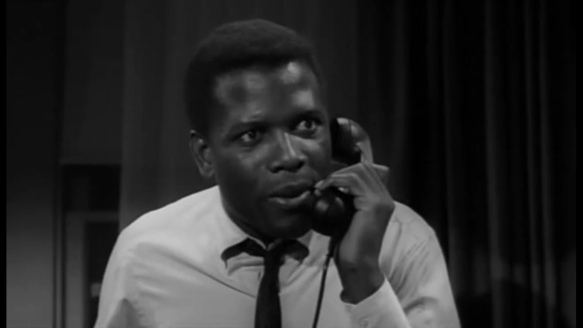

At last, I have rectified the situation and gotten to know the man who developed his own distinct persona from the others, “a Little Elf” built solely out of his meek even child-like affability in all situations.

The Strong Man is arguably his most prominent picture then and now. Worth noting is Frank Capra who made his directorial debut and right from the outset you can see some of his imprint on the story. Harry Langdon is staked out behind a Gatling gun in Europe as a meek Belgium soldier fighting against the enemy. However, he’d much rather use his slingshot, and he’s quite effective in tormenting his burly enemy in the trench only meters away.

This is merely an opening gambit. Soon it becomes an unmistakable immigrant tale with all the iconography most Americans will be familiar with. An ocean linter. That majestic beacon of hope: Lady Liberty. And of course, Ellis Island, that customary weigh station where people stopped off to begin a new life.

By some strange development, the Belgian has joined forces with his former enemy playing sidekick to the severe-looking strong man. However, the big city brings with it a lot of distractions for someone just off the boat and easily targeted.

Standing at a street corner, Paul gets mixed up with an archetypal city woman who only pretends to seduce him so she can retrieve the money she hid on his person. All manner of taxi rides and rendezvous in her apartment leave him quivering with fear. He’s much too timorous and naive to know what to do with himself in such a position.

This is, after all, the source of his charms. It suggests the image of Harry Langdon quite candidly. Not only is he a meek and unassuming hero, there’s this prevailing innocence about him. We could say the Tramp has some of the same, but Harry feels even more forbearing. He could never raise The Kid. He is the kid. In fact, he’s almost manhandled by the city woman as she locks the door and looks to retrieve what’s hers. It plays as a fairly comical power dynamic. This is only one bit.

The latter half of the picture feels much more Capraesque considering themes of graft and corruption in the face of common decency. There are precursors to his Miracle Woman where a barn becomes a clearinghouse for the local town’s vices, whether it be gambling, carousing, showgirls, beer, or pugilism.

The lines are drawn fairly clearly when Cloverfield’s corrupt kingpin sits down with the local parson trying to literally buy him out. He tells the old saint to name his price, and he’s absolutely indignant at the offer. We read his retort: “The House of God is founded on rock. For the miseries you have caused, the Master will destroy you!”

It’s not quite fire and brimstone, but it is very close. His congregation piles onto the lawn in front of his house as he rallies them with the story of Jericho and the exploits of Joshua where the God of Israel caused the walls of the great city to come tumbling down in His divine timing.

What I can only imagine is a rousing round of “Onward Christian Soldiers” leads them into battle as they begin their crusade around the Palace. This might be the time to insert that the looped scoring is a bit nauseating and as with many such silent pictures, it doesn’t seem to do the movie justice.

But we’ve failed to talk about the Belgian. Rest assured, he’s still relevant as he was once pen pals with the preacher’s daughter: Mary Brown, and of course, to make her all the more sympathetic, she’s blind. He doesn’t actually know she’s in town. He’s there as a part of a show on the lascivious stage. And he’s thrown to the wolves when his boss gets drunk.

He becomes the strong man. It’s another pitiful setup. But it’s the heart of the movie and a Capra moment of David vs. Goliath exploits. The little guy standing up against the masses in this case, literally holding them off with a makeshift cannon as their temple of sin topples all around them, and they flee into the streets.

If he’s partially David, then he’s part Samson crossed with a flying trapeze artist. Far from being a piece of irony, if we are to recall the preacher’s scriptures, “When I am weak, then I am strong” never sounded more pertinent.

His final stand is ample enough to save the town and bring about a newfound tranquility where he is a beacon of law & order while still taking a helping hand from Mary Brown. Per convention, they walk off into the sunset together a very happy couple and all is right with the world.

Harry Langdon is not talked about that often amid conversations of silent cinema. Part of the reason might be because he doesn’t have a row of feature-length films that are easy enough to lay claim to as his personal masterpieces. The Strong Man is as close as he came and with the fledgling name of Frank Capra — directing his first feature, no less — it has the benefit of some added name recognition.

Langdon is a relentlessly amicable hero, but that might be part of the issue. What you see is what you get, and it doesn’t add up to anything more. His understated persona is highly palatable but rather blase even in comparison to a few of his contemporaries. At the end of the day, The Strong Man can be viewed as a stepping stone in Capra’s own illustrious career — a step forward in his maturation of a filmmaker. It might be for someone else to make the case for Harry Langdon and resurrect him for the modern generations.

3.5/5 Stars