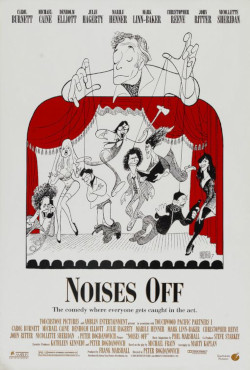

In the olden days, a stage production — or shall we say “the theater” — was blessed with a certain cultural cachet not extended to moving pictures. While this dichotomy hasn’t totally eroded, given the directions movies have gone, Noises Off…is buoyed by the stage for another reason.

Rarely have I witnessed something that totally blurs the line between performance and reality in such a self-reflexive manner. Noises Off… began as a highly successful play about a stage production going off the rails due to inadequate rehearsal times and the backstage histrionics of an amorous cast of characters. In other words, the original form fits the function.

Just by merit of the medium of film, it cannot be as intimate as the stage nor is it performance art in quite the same manner, though the director tries to stretch out sequences as long as they will contort to maintain the pace.

But the stage, because it is live, requires actors who are able to keep up with the utter mayhem of the material like trained athletes. Both the controlled and wildly chaotic nature interpolate into one storyline. So you obviously lose some of that instant spontaneity acquired by no other means.

If anyone knows that fact it’s Peter Bogdanovich, an avowed theater aficionado. He doesn’t let the story sag; it’s always zooming along, and it still manages something almost palpable. The trick is not fiddling too much with the concept nor trying to contort it in some grandiloquent way to fit the cinema.

The structure of the story itself is just as crucial in developing this cumulative impact. The Three Act Structure begins with the frantic rehearsal hours before they are set to perform. The long-suffering director (Michael Caine,) who might be on the edge of a nervous breakdown, is running out of time and dealing with temperamental actors asking for motivations or just absent-mindedly showing up late to set. He’s also romancing his leading lady (Nicolette Sheridan). The issues are there for comedic effect, but we have yet to reach impact — that requires a theater full of people.

Next, we follow the show from behind the curtain. The preparations are frantic, actors are missing, and the backstage crew, Julie Haggerty and Mark Linn-Baker, run around like two stage chickens with their heads cut off. It doesn’t change when the performance begins either because the whole story is based on timing — cues and a bustling scenario with slamming doors and traded props. It’s everything we’ve already seen, albeit from the inside out, ignited by male feuds (John Ritter gives Christopher Reeve a bloody nose) and private lover’s quarrels filled with bitter malice.

The show from the cheap seats is the worst (or best) of all as this mounting discontentment disrupts the foregone storyline with all kinds of private barbs and acts of pettiness played out on the stage. The key is how the fictional audience eats it all up because each absurd miscue feels like the next great flashpoint of brilliant comedy. It’s the height of farce.

One of my few reference points is Hellzapoppin’ even as the earlier film was often about the endless possibilities of non sequiturs. What they have in common is this almost Vaudevillian sense of gags and payoffs — where each character has a shtick that can be called upon at any given moment. This isn’t method acting so objects don a different meaning as tokens to carry out gags, and Noises Off… brings them to a fever pitch. Sardines and telephones, flowers and bottles of bourbon. A pickaxe bandied about by all, each carrying varying attentions.

They effectively blend the space where two planes of existence bleed into one because these same tokens are exchanged and traded both on the stage and behind the stage. I joined the fictional audience in laughter even more heartily because, in many ways, we get to see the interworking of the beast in all its comedic underpinnings.

If we’re observant and stay with them, we see where the story has gone off the rails and the “unscripted” chaos that exerts itself on the storyline. The so-called “audience” snarks at each snafu because it’s a hilarious faux pas — the pratfalls are even better because they are “real.” And here you have the joy of Noises Off where it brings out these double-meanings or double realities and fictions.

We get the benefit of being both an audience member and a backstage observer. Because we know that all this world’s a stage and all these people merely players. Like Hamlet, it is only a play within a play, but it broaches into our space with startling verve and a raucous sense of precision.

I am reminded of the security guard; he sits in the wings watching all the madness quizzically with a raised eyebrow. What a crucial insert he proves to be because comedy is so much about the reactions to the stimuli. He reminds us how zany all this fracas is just in case we need a point of reference — a threshold to ground us back in reality.

Since they cannot help being in a cinematic space, the cast is tip-top including some faces I’m often quick to forget about and others who I miss dearly. John Ritter and Christopher Reeve are a joy even if this is hardly remembered compared to their greatest exploits. Carol Burnett is a comedic jewel. Bless her. Marilu Henner brings back all those fine memories of Taxi reruns. Denholm Elliot had such a long and illustrious career, but a doddering part such as this made me appreciate him even more.

The transition from stage to screen would not work as whole-heartedly without its cast, and I love them all in spite of their doltishness. In fact, it’s probably precisely because of this the movie works. Noises Off...would have been quite the sight to behold on stage, but it doesn’t lose all its merits in the hands of Bogdanovich, who makes it still a worthwhile and totally jocular experience. My primary barometer was my own personal reservoir of laughter. I couldn’t control it, and that speaks volumes enough for me.

3.5/5 Stars

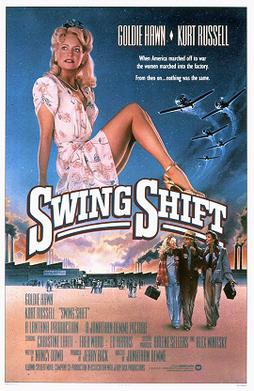

Aside from films actually produced during the war years, I’m not sure if I can think of a film that highlights the homefront to the degree of Swing Shift. The soundtrack is also perfectly antiquated (sans Carly Simon) fitting the era and mood to add another definite dimension. It effectively takes us back with the auditory cues of Glenn Miller, Hoagy Carmichael, and the rest.

Aside from films actually produced during the war years, I’m not sure if I can think of a film that highlights the homefront to the degree of Swing Shift. The soundtrack is also perfectly antiquated (sans Carly Simon) fitting the era and mood to add another definite dimension. It effectively takes us back with the auditory cues of Glenn Miller, Hoagy Carmichael, and the rest. There’s something apropos about baseball having such a central spot in the storyline of Parenthood because this is a movie wrapped up in the American experience from a very particular era. Yes, the euphoric joys and manifold stressors of parenting are in some form universal, but Ron Howard’s ode to the art of childrearing is also wonderfully indicative of its time.

There’s something apropos about baseball having such a central spot in the storyline of Parenthood because this is a movie wrapped up in the American experience from a very particular era. Yes, the euphoric joys and manifold stressors of parenting are in some form universal, but Ron Howard’s ode to the art of childrearing is also wonderfully indicative of its time.