It’s nearly ubiquitous for all the old war movies to open with an instructive title card supplying some context and placing us in the scenario at hand. While not the apex of visual storytelling, it does serve a concrete purpose. Objective Burma is, of course, about the Burma campaigns — the toughest road — opening a corridor that had to be opened. It proved to be a combined operation across the spectrum of Allied forces, and the first ones to go in were the paratroopers.

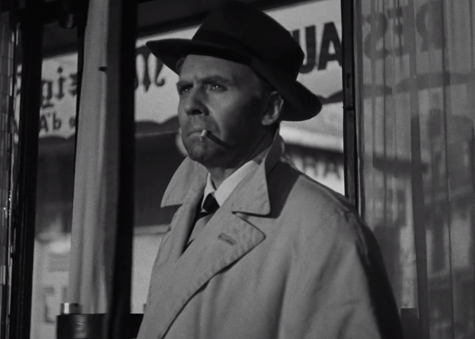

This is where our specific story begins. It must be noted the events have been conveniently recast and, therefore, the history books were rewritten for the sake of Hollywood convenience. At first, you assume Errol Flynn might be a Brit until you realize all his crewmembers are tried and true Americans. And he’s one too.

From then on, we know where our picture stands. In fact, everyone else — aside from a Chinese ally and their native guide — American. Two personal favorites would be the ever-wise-cracking Richard Erdman (who passed away in 2019) and George Tobias, always good for a couple of jabs at his mother-in-law. Look close enough and you’ll even pick out a young Hugh Beaumont while veteran actor Henry Hull plays an Ernie Pyle war correspondent-type.

I find the script, penned by Ranald MacDougall and loaded with witticisms, useful in building unique voices all throughout the company, even offsetting all the typical wartime shop talk. The idiolect of each is conveniently differentiated so even in the melange of personalities, we get a flavor instead of a muddy amalgam of white noise. It serves the picture well, especially due to its substantial running time.

The terrain is fittingly immersive, but sometimes it feels that instead of finding the action within the environment, the story is content in simply being a nature tour, moment by moment. It remains some small comfort having James Wong Howe. His work in transforming Los Angeles County Arboretum and Botanic Garden into the miry underbrush of East Asia is quite the feat. One is reminded how Sam Fuller turned another section of Los Angeles — the grounds of The Griffith Observatory — into Korea for The Steel Helmet. In both cases, it works.

Their first task is to take out an enemy radar tower, and it couldn’t be easier. They quite literally catch the Japanese out to lunch and calmly mow them down after their forces have fanned out into position. It’s a bit like a video game, if not like shooting fish in a barrel.

Surely the rest of the movie cannot be this easy even as it remains flippant toward the enemy, continually referred to pejoratively as “Japs” or “Monkeys. It’s too true. Their subsequent air pickup has to be aborted due to imminent enemy forces, and Captain Nelson (Flynn) splits his unit up to find a new checkpoint. Though disoriented, his command is held together. The other contingent is not so lucky with only a few stragglers making it back unscathed.

One of the mortally wounded, cradled in the arms of his buddy, says he’s never seen anything like it. It was a slaughterhouse. The Japanese were waiting for them in a clearing and mowed them down. Later, when the remnant tries to recover the rest of the dead, they realize the maimed bodies of their comrades carved to pieces, all but unrecognizable, if not for their dog tags.

It’s this brand of sadism that makes antipathy toward the Japanese enemy that much easier. It’s not an out and out lie. We know these types of despicable practices took place in service to the radicalized nationalist ideology. When men become so arrogant and callous, their capability for evil only intensifies.

What is problematic is not that the enemy is all but faceless; it comes down to the same issue of mowing down the Japanese earlier. There is a double standard we often hold ourselves to. It’s another incongruity. Consider the fact that, in real life, prisoners taken by the Allies would have been executed in order to move forward with the operation. It makes pragmatic sense. In the film, they’re conveniently killed off in the opening skirmish so there’s no need to show the messy business. To be clear, it’s not a matter of making allowances for the enemy but realizing the shades of gray in our own conduct.

At the midpoint, one cannot repudiate the fact our covert operatives are no longer the chipper aggressors soaring toward victory. Their ambitions are now forced to become even more elemental. Somewhere around this juncture, Objective Burma ceases to be a war movie and becomes a fraught survival story.

The straits are dire. They’re all but trapped, surrounded by enemy forces patrolling on all sides, and the grind — not to mention the loss of their comrades — is grating on them. Morale begins to crumble as fatigue sets in. The bottom line is that they never cave completely in either regard, despite the hardships in the jungle.

One might chalk it up to their leader, and it’s true Flynn commands with a strong yet compassionate fortitude. He cares deeply about the well-being of his men, even as he stands unswervingly by the orders they’ve been designated with. Upon receiving word to disregard all previous orders, they get ambushed in a clearing over a supply drop and vaguely chart a course north to a destination they don’t know. They’re following orders, clinging to the hope of some deliverance. But even if there is help coming, the enemy knows their position.

In one final stand, they entrench themselves on a hilltop, sweating it out into the wee hours, surrounded by a maze of tripwires to keep the Japanese at bay. They are outnumbered, the enemy cloaked in darkness, looking to overtake their position. I cannot think of anything more terrifying.

Their triumphant stand is made in an instance of clarity, thanks to a flare lighting up the night sky, and a barrage of grenades they’re able to lob at their retreating enemies. The film see-saws back toward one side decimating the other. It’s a pulse-pounding final setpiece still underlined by this sense that the “good guys” won so all is well. Understandably, in 1945, there need not be any ambiguity to the moral gradient.

The story of why Flynn found himself only playing soldiers and never actually being one is a subject of some personal mortification. His laundry list of ailments went beyond his bad heart to purportedly include tuberculosis, malaria, and back problems. True to form, the studio kept it all conveniently on the down-low — quelling any leakage as to maintain the image of their masculine star. Of course, it created a bit of dissonance in the wartime years.

One of the curious results was the observation Flynn was never more malleable and easier to work with than during his wartime cycle of films. Whether it was his embarrassment in not being able to fight himself or his drive to do his part in Hollywood’s propaganda machine is not clear; although it may have been some of both.

Because, in 1945, I hesitate to say Errol Flynn was on the way out, but certainly with the end of WWI,I and the beginning of the post-war years, it was a time meant for a more youthful batch of matinee idols and stagy rebels meant to reflect changing times.

By 1959 Flynn would be dead, his career plummeting to its conclusion due to hard drink and hard living. For now, he still fit the ideals of the generation but even that had to be doctored by Tinsletown to hold onto the last vestiges of one of the 1930s preeminent action icons. The war changed everyone. Even Errol Flynn.

3.5/5 Stars