While a less heralded picture, this Billy Wilder film is a minor classic built around a contrived comedic situation. Dean Martin opens playing a parodied version of himself as Dino the boozing, womanizing, but altogether good-natured playboy who makes a short pit stop in the gas station of the small town of Climax, Nevada following his latest Las Vegas circuit.

While a less heralded picture, this Billy Wilder film is a minor classic built around a contrived comedic situation. Dean Martin opens playing a parodied version of himself as Dino the boozing, womanizing, but altogether good-natured playboy who makes a short pit stop in the gas station of the small town of Climax, Nevada following his latest Las Vegas circuit.

The beauty of his performance, though it may be exaggerated, there is no sense that this is a thinly veiled caricature. It’s blatantly obvious that “Dino” as he is called in the film is really only playing his “Rat Pack” persona that was known the world over.

That sets the groundwork for the film’s self-reflexive nature that is keenly aware of its cultural moment and the preoccupations of the general public as with many of Wilder and I.A.L. Diamond’s best scripts.

Truthfully I’ve always been fond of Ray Walston ever since my first viewing of My Favorite Martian and before this picture, he cropped up in Billy Wilder’s The Apartment (1960). Although I do adore Peter Sellers (who had to bow out due to a heart attack) and he’s often an ad-libbing genius, somehow Walston seems to more aptly fit the bill here.

That doesn’t mean I don’t regret that Jack Lemmon couldn’t take the role because he really was Billy Wilder’s greatest comedic counterpart, portraying every bit of neuroses that manifests itself in the middle-class everyman. He just gets it and putting him opposite his real-life wife in Felicia Farr would have been another delightful ironic layer to this comedy with its roots in infidelity.

No matter. It was not to be and what we are left with is still some fairly hefty star power. Walston audaciously takes center stage as Orville Spooner, a small town piano teacher with a paranoid fit of jealousy in relation to his gorgeous wife (Felicia Farr). He believes everyone from his teenage pupil to the local milkman is out to pluck his bright-eyed, loving bride away from him.

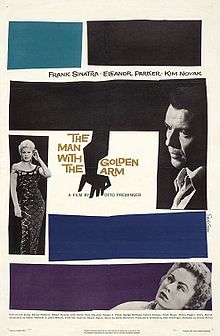

That’s of the utmost importance when his buddy (Cliff Osmond) dreams up a plan to get themselves a contract deal with Dino. It involves hosting the conveniently laid up pop singer, getting rid of Orville’s wife, and employing the services of one of the main attractions at the local watering hole The Belly Button — the one and only Polly the Pistol (Kim Novak). It seems simple enough to get her to masquerade as Orville’s wife just for the evening so she can make Dino feel at home.

You can see already that the narrative is entangled with bits and pieces of The Apartment (1960) and The Seven Year Itch (1957). Miscommunication and four parties involved means all sorts of foreseeable consequences. Kiss Me, Stupid is also fully aware of the contemporary Hollywood framework much in the same way of Sunset Blvd. Thus, it’s not above satirizing the ways of the entertainment industry — especially the movie stars — with the Rat Pack placed front and center thanks to Martin.

The small-time piano man and gas station attendant also have dreams of being the next Henry Mancini & Johnny Mercer dynamic duo with aspirations for The Ed Sullivan Show no doubt.

Even in its throwaway lines about churchgoers, there’s something starkly sobering being acknowledged as there are in many of the things that Wilder finds time to take a jab at. The owner of the Belly Button, Big Bertha, has all her girls attend the local church because she thinks it’s good for public relations.

It passes like a blip but the suggestion seems to be that these lines of dialogue and what we see on screen might point out some kind of hypocrisy and although it’s played for comedy, instead what I see is the inherent brokenness.

The film spins in such a way that the infidelity somehow ends in a kind of loving understanding that feels like utter absurdity but maybe Wilder has done that on purpose. Still, in spite of myself, I found some humor in this film in ways that I never could in The Seven Year Itch or The Apartment.

The first was too empty with little to offer of substance and the second is often too stark and morose to be funny. This film is raucous and utterly insane in a sense but that’s the way Wilder likes it from Some Like it Hot (1959) to One, Two, Three (1961). Kiss Me Stupid isn’t such a spectacular comedy with some misfires but there’s no doubt that Wilder still has his stuff.

He always seemed to take a very basic concept that was wacky and far from allowing it to fizzle out, he sees it to completion, finding an ending that derives laughs while simultaneously providing wry commentary.

In another screenwriter’s hands or another director for that matter, the romantic comedy aspects would be endangered of becoming trite and uninspired but no such issue here. Wilder would never allow it.

The punchline of Kiss Me, Stupid is that both spouses were deceptive and unfaithful but they do it out of love — that final touch of trenchant Wilder wit. Ultimately, the film’s title is reminiscent of the famed quip in The Apartment (1960), “Shut up and deal.” You get the same sense of the relationship.

The men are essentially cads — spineless at times — and lacking much of a moral makeup (even if Orville plays the organ at church) but their women seem to give them some substance whether they be barmaids or plucky housewives. It’s still slightly mindboggling that Wilder pulled this movie off and got away with it no less.

3.5/5 Stars

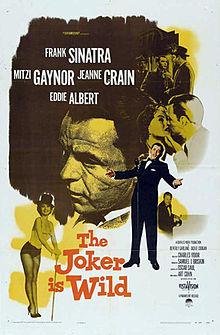

It required quite the journey to make it to this film, starting out with a different joker entirely. My introduction to comedian Joe E. Lewis happened because of the late, great Jerry Lewis. Revisiting his life and work I made the discovery that the comedian changed his name to avoid confusion with two men. First, Joe Louis the stellar boxer of the 1930s and then Joe E. Lewis the comedian.

It required quite the journey to make it to this film, starting out with a different joker entirely. My introduction to comedian Joe E. Lewis happened because of the late, great Jerry Lewis. Revisiting his life and work I made the discovery that the comedian changed his name to avoid confusion with two men. First, Joe Louis the stellar boxer of the 1930s and then Joe E. Lewis the comedian.

Hacksaw Ridge is not for the squeamish, its greatest irony being that for a film about a man who took on the mantle of a conscientious objector and would not brandish firearms, it is a very violent film, even aggressively so. But Mel Gibson, after all, is the man who brought us Braveheart (1995) and The Passion of the Christ (2004) while starring in The Mad Max and Lethal Weapon franchises.

Hacksaw Ridge is not for the squeamish, its greatest irony being that for a film about a man who took on the mantle of a conscientious objector and would not brandish firearms, it is a very violent film, even aggressively so. But Mel Gibson, after all, is the man who brought us Braveheart (1995) and The Passion of the Christ (2004) while starring in The Mad Max and Lethal Weapon franchises.