The finest compliment that can be paid to Blade Runner 2049 is that it is indubitably the most enigmatic film I have seen in ages. Typically, that’s newspeak for a film that probably deserves multiple viewings, because its intentions, much like Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) are not always clearly laid out. Especially in this day and age when we often expect things to be given to us and our hands to be held as an audience.

The finest compliment that can be paid to Blade Runner 2049 is that it is indubitably the most enigmatic film I have seen in ages. Typically, that’s newspeak for a film that probably deserves multiple viewings, because its intentions, much like Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) are not always clearly laid out. Especially in this day and age when we often expect things to be given to us and our hands to be held as an audience.

For that very reason, those who admired the original will potentially find a worthy successor in Denis Villeneuve’s rendition but this cult franchise might be hard-pressed to convert a new fanbase. Because while the greatest cinematic achievements are often equally artistic endeavors and continually entertaining, Blade Runner is worthy of the former while still lacking the kind of visceral fun that will grab hold of a new generation.

Still, there’s a necessity to draw up a distinction between faulty pacing and a film that is completely comfortable moving at the pace it deems important. The film paints in panoramas and epic strokes that the Ridley Scott’s original simply could not manage. Though perhaps more importantly, it did develop a cyberpunk, tech-noir aesthetic that created a new template for so many future projects.

The veteran cinematographer and Villeneuve favorite, Roger Deakins, produces visual splendors of the first degree with his own brand of photography. They are the kind of immaculate frames where shot after shot can be admired each one on its individual merit as if perusing a vast gallery of paintings. One important key is that oftentimes we are given enough time to take them in without frenetic editing completely cannibalizing the pure joy of a single image.

It can similarly be lauded as not merely a piece of entertainment for thinking people but a piece of visual art and a philosophical exploration. That last point will come up again later.

But it’s also quite easy to liken this installment to George Miller’s Mad Max Fury Road (2015) which was able to provide a facelift to its material by successfully expanding the world that had been built in the original Mad Max trilogy. Likewise, this movie maintains much of the integrity of its predecessor by seeing the return of several cast members, screenwriter Hampton Fancher, and even Ridley Scott to a degree as executive producer.

Our story in this addition begins with a new model of replicants, Nexus-9, who are used as the current force of blade runners as well as other more menial duties. Among their ranks is K (Ryan Gosling) an officer assigned by his boss at the LAPD (Robin Wright) to track down the last remaining rogue models of “skin jobs” still surviving.

Simultaneously the Tyrell Corporation has been replaced by a new organization led by a visionary named Wallace (Jared Leto) who has aspirations to create an even more magnificent android in search of true perfection of the human form. He’s also very much interested in a mysterious discovery that K makes while performing his duties.

Wallace sends out his henchwoman (Sylvia Hoeks) to do his recon for him. Meanwhile, K travels far beyond the metropolis of Los Angeles with its unmistakable imagery full of Coca-Cola ads, Atari game parlors, and countless women walking the streets looking to pick someone up.

It’s comforting to know that my home away from home, San Diego, has been turned into a giant rubbish heap while Las Vegas looks more like the Red Planet than any earthly locale though still strewn with the remnants of the strip’s sleaze. If we ever took for granted that this is an apocalyptic world then we don’t anymore.

In keeping with the integrity of the picture and the curiosity of the viewers, it’s safe to say that Edward James Olmos makes his return as Gaff still partaking in his origami-making ways though his subject matter has changed slightly. And of course, the man everyone has been waiting for, Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) is of crucial importance that becomes at least a little bit more clear as K progresses in his search for concrete answers. The cornerstone of the story is, of course, Deckard’s beloved Rachael and the life of anonymity he has taken up since his retirement as a blade runner.

But until its very last frame Blade Runner 2049 feels cryptic and mesmerizing in a powerful way. The narrative is so expansive and grandiose making it questionable whether or not the film is able to maintain a cohesive core with a singular purpose but some potentially profound ideas are undeniable.

Plenty of spiritual imagery courses through it and hardly by accident. An almost Christ-like birth of a supernatural nature remains at its center and what we can presume to be several very conscious references to the book of Galatians — a letter that not only tackled the so-called “fruits of the spirit” but Gnosticism or the idea that the Creator was a lesser divinity (not unlike Wallace).

Upon reflection, I’m still partial to the original because while both films grapple with the dividing line between the human and the non-human, the first Blade Runner came from a human perspective and that’s even in how it was shot and the technology of the time. It looks like our world, dark, dank, and gritty as it may be.

But in this narrative, while a further extension of that same world much of what we know is in question and it hardly feels like we are taking on a human point of view anymore but we are put in the place of a replicant — an android — even if he has a desire to be human. And again, that lack of humanity reveals itself in the very frames of the film full of unfathomable sights acting at times like a tomb-like mausoleum– so bleak and austere and cavernous.

That is to say that the original even in its darkness still managed to have a soul in the incarnation of Deckard. This picture though trying so desperately to do likewise feels even more detached. It, in some ways, brings to mind Gosling’s Drive character who was very much the same. And yet the other side still deserves some acknowledgment because there is an underlying sense that K does evolve into a more sympathetic individual as time passes. The case can be made that he is the most human.

Going beyond that, it’s also an exploration of how the world is saturated with sex and probably even more so than its predecessor. There’s a particularly unnerving scene where a man tries to combine fantasy with physical intimacy in a way that feels all too prevalent to our future society and consequently it brings up similar themes to Her (2013).

Even in such a future, it’s comforting to know that Presley and Sinatra live on in the hearts and the minds of the populous though that reassuring truth cannot completely overshadow the myriad of issues still to be resolved.

The final irony remains, the problems do not begin with the replicants themselves but in the hearts and souls of mankind. I see that central complexity of the film very clearly reflected in the two iconic objects. One an origami unicorn, the other a wooden horse.

Because we can read into the first if we want to as an indication that Deckard is a replicant and we can see the latter as confirmation that K is, in fact, human and yet on both those accounts we might be gravely mistaken. It comes downs to our own personal perceptions. Whether these beings were “born not made” or vice versa.

It gives more credence to the assertion that the eyes remain the window to the soul. That is never truer than in Blade Runner a film that fittingly opens with a closeup of an eye — the ambiguity established in the first shot. As K notes later, he’s never retired something that was born. Because “to be born means you have a soul.”

Of course, that razor-thin dividing line can be very difficult to dissect completely and that’s Blade Runner 2049 stripped down to arguably its most perplexing issue. Could it be true that an android could act with far more humanity than any human? The verdict might well be out far longer than 2049.

4/5 Stars

“A picture with a smile — and perhaps, a tear…”

“A picture with a smile — and perhaps, a tear…”

Though it’s easy to be a proponent of

Though it’s easy to be a proponent of  “Doesn’t it ever enter a man’s head that a woman can do without him?” ~ Ida Lupino as Lily Stevens

“Doesn’t it ever enter a man’s head that a woman can do without him?” ~ Ida Lupino as Lily Stevens

In Manchester by the Sea, you can distinctly see Kenneth Lonergan once more translating some of his skills as a playwright and stage director into his film. There’s a very inherent understanding of two-dimensional space and how images can be framed in a very linear way as they would be seen by an audience taking in a stage production. But even more noteworthy than that is his dialogue which functions in remarkably realistic ways. Some will easily write this film off as the sheer doldrums because it’s fairly fearless in its pacing.

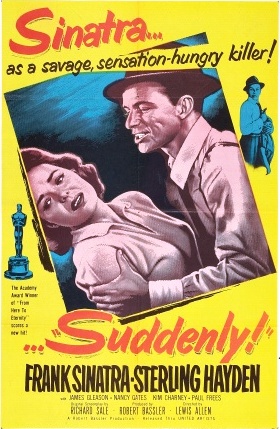

In Manchester by the Sea, you can distinctly see Kenneth Lonergan once more translating some of his skills as a playwright and stage director into his film. There’s a very inherent understanding of two-dimensional space and how images can be framed in a very linear way as they would be seen by an audience taking in a stage production. But even more noteworthy than that is his dialogue which functions in remarkably realistic ways. Some will easily write this film off as the sheer doldrums because it’s fairly fearless in its pacing. In some ways, the sleepy town of Suddenly feels like it could have easily been the prototype for Mayberry (Willis Bouchey’s appearance acting as the one actual tie-in to The Andy Griffith Show). The sheriff wanders around lazily. He knows everyone by name and they probably haven’t had anything exciting actually happen for 20 or 30 years at least. But then they go and have something bigger than Mayberry ever dreamed. No filling station robberies, or shipments of gold, or even a group of out of towners trying to case the bank. This is big. It involves the President of the United States and Frank Sinatra or rather Johnny Baron, the man who`s looking for a big payday from assassinating the commander in chief. But people generally liked Ike and so the Secret Service roll in to take the necessary precautions including cueing in the local sheriff on the particulars and shutting down the town.

In some ways, the sleepy town of Suddenly feels like it could have easily been the prototype for Mayberry (Willis Bouchey’s appearance acting as the one actual tie-in to The Andy Griffith Show). The sheriff wanders around lazily. He knows everyone by name and they probably haven’t had anything exciting actually happen for 20 or 30 years at least. But then they go and have something bigger than Mayberry ever dreamed. No filling station robberies, or shipments of gold, or even a group of out of towners trying to case the bank. This is big. It involves the President of the United States and Frank Sinatra or rather Johnny Baron, the man who`s looking for a big payday from assassinating the commander in chief. But people generally liked Ike and so the Secret Service roll in to take the necessary precautions including cueing in the local sheriff on the particulars and shutting down the town. The finest compliment that can be paid to Blade Runner 2049 is that it is indubitably the most enigmatic film I have seen in ages. Typically, that’s newspeak for a film that probably deserves multiple viewings, because its intentions, much like Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) are not always clearly laid out. Especially in this day and age when we often expect things to be given to us and our hands to be held as an audience.

The finest compliment that can be paid to Blade Runner 2049 is that it is indubitably the most enigmatic film I have seen in ages. Typically, that’s newspeak for a film that probably deserves multiple viewings, because its intentions, much like Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) are not always clearly laid out. Especially in this day and age when we often expect things to be given to us and our hands to be held as an audience. Upon watching A Few Good Men for the first time, it was hard not to draw parallels with An Officer and a Gentlemen for some reason and it went beyond some cursory elements such as both films involving branches of the military. Perhaps more so than that is the intensity that manages to surge through the plot despite the potentially stagnant battleground like Cadet Schools, Courtrooms, and the like. And that can in both cases is a testament to the stellar performances in front of the camera.

Upon watching A Few Good Men for the first time, it was hard not to draw parallels with An Officer and a Gentlemen for some reason and it went beyond some cursory elements such as both films involving branches of the military. Perhaps more so than that is the intensity that manages to surge through the plot despite the potentially stagnant battleground like Cadet Schools, Courtrooms, and the like. And that can in both cases is a testament to the stellar performances in front of the camera.