The film commences brilliantly as Frances Dee can be heard in voiceover with almost fond recollection, matter-of-factly stating, “I Walked with a Zombie.” The way she expresses it immediately debunks anything we might think from an admittedly exploitative title. Producer Val Lewton does not settle for a straightforward slapped together horror flick.

The film commences brilliantly as Frances Dee can be heard in voiceover with almost fond recollection, matter-of-factly stating, “I Walked with a Zombie.” The way she expresses it immediately debunks anything we might think from an admittedly exploitative title. Producer Val Lewton does not settle for a straightforward slapped together horror flick.

His ambitions were always to elevate the concepts he was handed into something indelibly interesting. Our heroine Betsy Cornell (Dee) is a Canadian nurse who applies for a position taking care of a man’s wife. It’s all very mysterious, but she’s eager to work and sets sail for San Sebastian where she will be in the service of Mr. Paul Holland (Tom Conway).

Lewton re-framed the source material into a Jane Eyre tale transplanted to the West Indies. Here Ms. Cornell arrives by boat, immediately struck with a callous first impression of the aloof Mr. Holland. He easily dismisses her childhood fear of the dark, while noting he never should have hired her.

I still contend most children are never afraid of the dark per se but what might come out of it. It’s the fear of an unknown thing lurking out of reach. Meanwhile, his younger brother (James Ellison) is a charming fellow who immediately takes a liking to the new nurse and helps to make her feel welcome. We have polar opposites set up and obvious points in a possible love triangle.

However, in following the plotting of Bronte’s work, the elder half-brother is tortured by a secret, literally locked away. It is, in fact, his mysterious wife, whom Betsy unwittingly meets one night, upon hearing a startling noise. At first, she’s taken aback by this specter of a woman, this ghost, this living dead.

But as her kindly doctor explains, supplying a firm foundation of ethos to this enigma, a portion of the spinal cord is burned out, and it has permanently made her a sleepwalker who can never be awakened. Aside from a potentially dangerous foray into shock therapy — to induce some sort of coma and hope for the best — her future prospects look dim. That is unless there’s an alternate means to bring about healing.

Like the Wolf Man before it, we are introduced to a stylized but nevertheless real locale that thrives by mixing the logical digressions that come from our world with ghostly influences. Screenwriters Curt Siodmak and Ardel Raye create a kind of poetic mythology for a supernatural conclusion to be crafted out of. Whether they meant to or not, they succeeded in canonizing zombies in the same manner werewolves were developed in Siodmak’s earlier script.

What’s lovely is how Betsy foreshadows all sorts of events to come and there are strangely mesmerizing objects to captivate us. The figurehead of a slave ship features Saint Sebastian himself pierced by arrows. It lends this undercurrent of the brutish injustices of the slave trade to the landscape we must come to terms with.

These very same traditions have the same weighty dolefulness but are also imbued with an otherworldly quality of its own. It gives this shading to the African-American characters who seem so happy-go-lucky like other Hollywood creations, and yet there’s an almost unnerving sense about them as if something is working under the surface. It’s hard to put an exact finger to it, but though they look similar, they aren’t quite straightforward stereotypes.

A local club singer chants an island song mixed with family folklore telling of the deep-rooted tragedies of the Holland family. The local populations are also adherents of local voodoo customs, and their nightly drumbeats ring out through the air ominously, picked up by the tropic winds. It’s yet another layer to this continually bewitching atmosphere.

Another character of crucial importance is Mrs. Rand, the deceased patriarch’s widow, and Wesley’s birth mother. Her own station in life, as the wife of a Christian missionary, creates a juxtaposition between a so-called normal religion and a darker, more dubious strain.

Because it cannot help but bump up against the voodoo rituals even as black and white people now exist together. In fact, one might say the religious rituals become nearly intertwined. Betsy begins to realize maybe some powers at be might be capable of lifting the spell that has entranced Ms. Holland, even as she herself falls for the comatose woman’s husband.

As such, it is not horror lingering over the frames but a near mesmerizing catatonia. It carries you up in its grips from start to finish, trying to decipher what to make of such a vision. Enchantment, ugliness, cruelty all apply. And yet it’s difficult to cry out and out evil against the people partaking in these dances or voodoo ceremonies. The acts themselves might be evil, but the people are held in the grips of entrancement. Everyone is, to varying degrees, weighed down with desolateness even before the fateful dead are laid to rest.

We must recall the beginning voiceover once more. The fact Betsy walked with a zombie might hold an inherent element of terror, but more so, it carries with it a despondency that cannot be lifted. It hangs over us and haunts us just as the lurching Carrefour does throughout the picture.

The beauty of most any of the Val Lewton films of the 40s is how the studio and the audience expected one thing — a low budget horror flick with a provocative title — then the producer turned around to make micro-budget gems steeped in shadow and psychology. They have more depth and complexity than they have any right to.

Each entry boasts sumptuous visuals hiding weaknesses in the budget department to fully develop, not necessarily a world, but the impression of a world. One might contend the latter is far more powerful in an expressionistic capacity. Arguably, Lewton had no more formidable collaborator than director Jacques Tourneur who had an established knack for conjuring up the most splendid atmospherics.

This time he is aided by the black and white photography of Roy Hunt. In their hands, every character has a doppelganger in the form of shadows creeping along the walls with their human counterparts. It’s developed with the utmost efficiency, which seems all but a lost art these days.

But the astounding economy is matched only by a ceaseless ingenuity. Because the artfulness they managed to accomplish on the very same shoestring budget, is part of what makes them marvels even today. If you willingly invest your time in one of these RKO pictures, it’s very likely you’ll be met with a lasting impression. The dividends, as far as cinematic capital is concerned, are enormous.

4/5 Stars

The western is founded on certain unifying archetypes, from drifters to revenge stories, showdowns and the westward progress of civilization butting up against the lawless wilderness. It always proved a fitting genre for morality plays and deeply thematic ideas. The tradition of the bank robbery goes back to Edwin S. Porter and The Great Train Robbery, and it plays an important role in The Naked Dawn.

The western is founded on certain unifying archetypes, from drifters to revenge stories, showdowns and the westward progress of civilization butting up against the lawless wilderness. It always proved a fitting genre for morality plays and deeply thematic ideas. The tradition of the bank robbery goes back to Edwin S. Porter and The Great Train Robbery, and it plays an important role in The Naked Dawn.

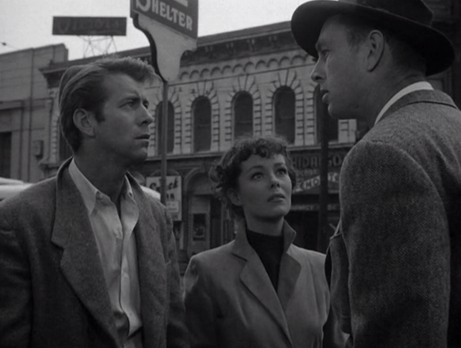

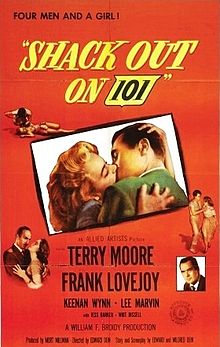

Like a Cry Danger (1951) or a Private Hell 36 (1954), this low budget film noir flick is such a joy to watch because it wears what it is right on its sleeve, clear out in the open. What we get is an utterly absurd paranoia thriller that also happens to be a heaping plate of B-noir fun.

Like a Cry Danger (1951) or a Private Hell 36 (1954), this low budget film noir flick is such a joy to watch because it wears what it is right on its sleeve, clear out in the open. What we get is an utterly absurd paranoia thriller that also happens to be a heaping plate of B-noir fun. It looks like we’re staring into a black hole. Disorienting. Dark. Swirling around us. Our eyes adjust as our narrator begins his voiceover that will cover the majority of the film’s canvas. In this moment he talks about that initial spark, that moment of birth when humans leave the womb behind and see the light of day for the first time. In that same instance, we burst into the open air and realize that what we were looking at all along was the long dark tunnel from a moving train.

It looks like we’re staring into a black hole. Disorienting. Dark. Swirling around us. Our eyes adjust as our narrator begins his voiceover that will cover the majority of the film’s canvas. In this moment he talks about that initial spark, that moment of birth when humans leave the womb behind and see the light of day for the first time. In that same instance, we burst into the open air and realize that what we were looking at all along was the long dark tunnel from a moving train. The rain is pouring down. A group of men sits in silence in truck cabs their heads full of all sorts of thoughts. Two more sit in the rear hoping the explosives sitting in their stead don’t decide to go Kablooie over the next bump. Nary a word is spoken, the entire sequence playing out in silence except for the inner monologues of each man.

The rain is pouring down. A group of men sits in silence in truck cabs their heads full of all sorts of thoughts. Two more sit in the rear hoping the explosives sitting in their stead don’t decide to go Kablooie over the next bump. Nary a word is spoken, the entire sequence playing out in silence except for the inner monologues of each man. B-films have little time to waste and this one jumps right into the action. In a matter of moments, a man is shot, another man has killed him and a third witness gets away into the night. Although Frank Johnson (Ross Elliot) is rounded up by the police to be a witness he gives them the slip for an undisclosed reason and they must spend every waking hour trying to track him down.

B-films have little time to waste and this one jumps right into the action. In a matter of moments, a man is shot, another man has killed him and a third witness gets away into the night. Although Frank Johnson (Ross Elliot) is rounded up by the police to be a witness he gives them the slip for an undisclosed reason and they must spend every waking hour trying to track him down.