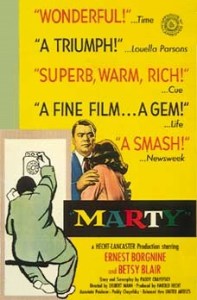

To my mind, Marty is the only movie adapted from TV to win an Oscar and certainly to get as much publicity as it did. During the surge of the Golden Age of Television, Paddy Chayefsky was king and Marty became a pinnacle of what could be accomplished by a writer with a singular voice.

To my mind, Marty is the only movie adapted from TV to win an Oscar and certainly to get as much publicity as it did. During the surge of the Golden Age of Television, Paddy Chayefsky was king and Marty became a pinnacle of what could be accomplished by a writer with a singular voice.

It’s a triumph of the small screen brought to the large, breaking down the boundaries and some of the prejudices that come with it thanks to the particular story it chooses to tell.

Marty is easy enough to place. He takes up residence in the territory Chayefsky would canvass in many of his stories including later efforts like The Catered Affair or Middle of The Night. There’s a “write what you know” imperative to his work. If it’s not quite realism — the words are too precise in their cadence and meter — then it certainly makes for unadorned cinema away from the normally watchful eyes of Hollywood.

Marty is a butcher and an unmarried man who lives with his mother. He’s kindly enough cutting up meat as the ladies of the neighborhood chide him that he should be getting married. All his siblings are hitched, and he’s the eldest and still alone.

It’s the earnest simplicity of the story that always appealed to me in the past. But as I grow older Marty speaks to me more and more. Because you begin to see it differently in light of new experiences and the kind of tensions that come with familial relationships and adulthood in general.

As I’ve gotten older and recall periods of singleness in my life and the lives of others, I’m all the more moved by Ernest Borgnine’s performance. He was always relegated to heavies. Like Raymond Burr, the only way to play the hero was on the small screen. Burr got Perry Mason and Borgnine got, well, McHale’s Navy. But before that, there was Marty (1955), and it was an unassuming film that proved to be a stirring success. It’s an underdog story in an industry predicated on prestige, star power, and publicity. Borgnine plays it beautifully.

On a Saturday night, he and his best bud Angie (Joe Mantell) drink beer together perusing the newspaper and quibbling over what they’ll do for the evening like a pair of vultures out of The Jungle Book.

At his mother’s behest, they make their way to the Stardust Ballroom to hopefully meet a couple of “tomatoes.” It feels a bit like a watering hole with dancing and fast music. All the various enclaves stand around looking for mates and finally stirring up the courage to meet someone. It’s a space where everyone gives everyone else the once-over before making a decision.

Social psychologists tell us that certain traits like facial symmetry, height in men, or hip-to-waist ratio in women have been the unconscious cues throughout the history of humankind. We’ve progressed toward swipes and likes and what have you, from the dance hall circuit, but it’s not too dissimilar. Just less personal and more commoditized.

It’s all still founded on the same premise of surface-level attraction. Obviously, there’s something to this. But whatever generation you hail from, it’s still a game of wooing and putting the best version of yourself out there.

Flaws and vulnerability might come but far later down the line when you know someone and can let your guard down. What makes Marty is how this butcher, who feels chewed up and spit out by the world’s mating game, finds someone to connect with on a far less superficial level. It begins with an observation.

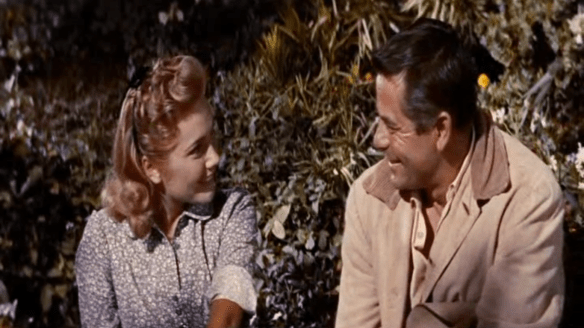

He notices someone else’s humiliation and reaches out to her because he knows what it is to be looked down upon and disregarded. And just like that Marty and Clara (Betsy Blair) are brought together into one another’s orbits. They start to share about their livesb and we learn she’s a school teacher who still lives with her parents. Marty gets so comfortable in her presence and starts babbling incessantly — it’s over the top — but it’s also lovable.

Borgnine and Blair are cast so well together, and it’s not because ’50s Hollywood assumed them to be plain. There’s such a sincere candor about them that comes out on the screen, and the movie requires this for their chemistry to work and for the sake of the story. We like them because they feel like us.

Marty admits, “Dogs like us, we’re not really as bad as we think we are.” He’s internalized the language of the culture at-large, but in the presence of a kindred spirit, he feels happy and more like himself, totally at ease in her presence. It makes me think of the advice that you should enjoy talking with your future spouse because contrary to popular belief, that’s probably what you’ll be spending most of your life doing together. Spending mundane moments in one another’s company.

They have a bit of a bubble for themselves of near-delirious happiness; the drama comes from all the outside forces weighing on them. The guys like Angie and that crowd are gruff and crude. They try and set Marty up with other girls and tell him Clara’s not attractive. Meanwhile, their conversations are full of vulgarities involving Mickey Spillane novels and magazine centerfolds.

But this is not the only criticism. Marty also hears from his mother, a deeply devout Catholic and Italian mother who cares about her family and her boys. She does not want to be discarded as an old maid and worries her son’s new, non-Italian girl will cause a rift between them like she’s already seen in their extended family.

It’s almost too much for him. Marty lives under the lie that he must conform and listen to what others speak into his life, and certainly there is some truth in considering the counsel of those around you.

However, sometimes it can also be pernicious and he realizes amid this sea of tedium and insecurity being projected onto him, he has something worth pursuing. Why would he ever consider giving that up? And so he gives up everything miserable, lonely, and stupid in pursuit of a priceless gift. In his relationship with Clara, Marty is a richer man than most.

4/5 Stars