I recall in middle school I was giving a current event on the horrible conditions in a hospital for war veterans. The handyman who just happened to be in our classroom overheard my report and was moved to speak. He shared his displeasure not at me but at a system that would so completely fail these people who had sacrificed so much.

As a film, Umberto D. ably tackles many of these same ideas while also suggesting to me how seamlessly Vittorio De Sica can move in documenting varying subsets of humanity. He’s often remembered for his child actors and the numerous untrained performers he put before his camera.

It’s a reminder of how, rather like Robert Bresson, he knew the types he wanted on the screen, “normal” people with features that have now become iconic all these years later. I think of Martin LaSalle in Pickpocket, Anne Wiazemsky, or even Balthazar the donkey.

But whereas Bresson always seemed to be engaged in his actors most specifically for their movements and how he could dispel them down to their most basic entities within the context of his films’ action, De Sica was always a director totally enamored with the contours of his characters as living, breathing human beings who have to go out and make a living like any of us.

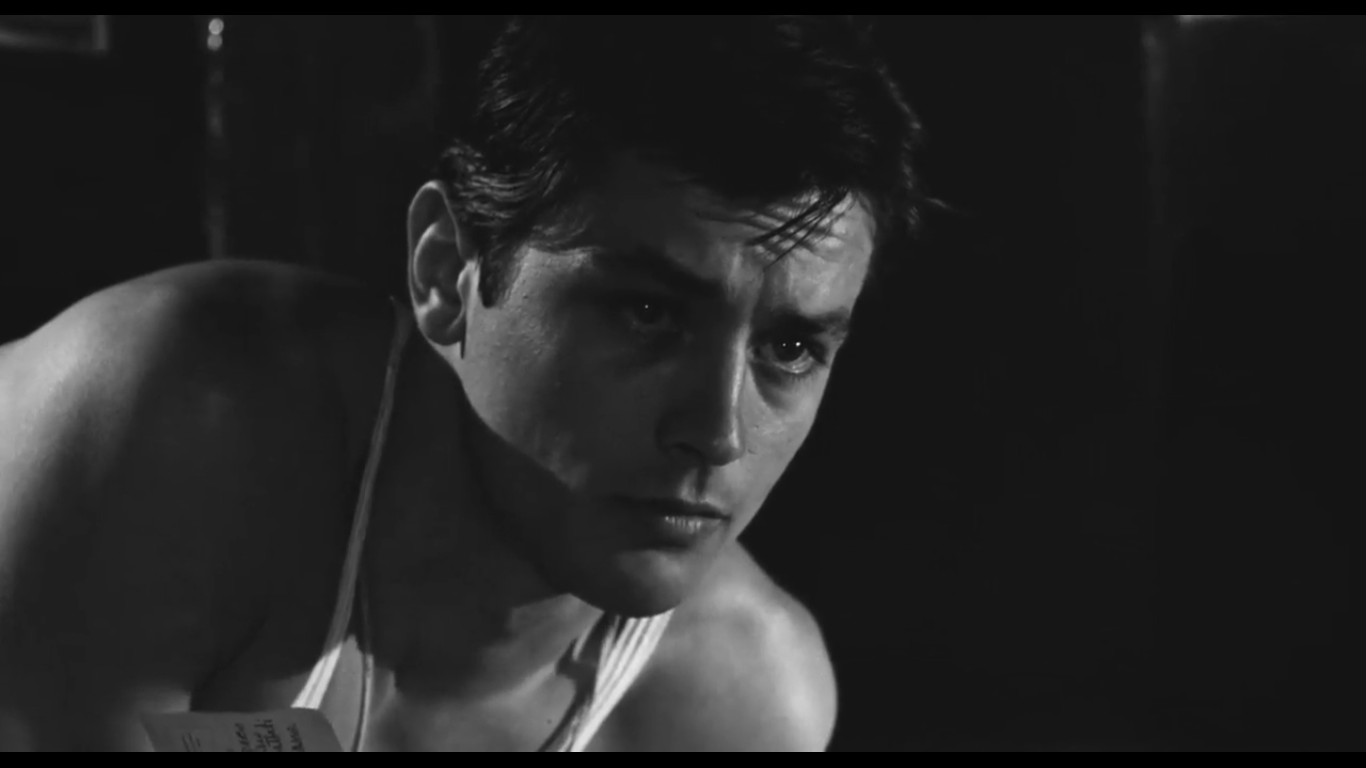

In Umberto D. it’s the eponymous character (Carlo Battisti) and his dog. Part of the magic is how De SIca found people who could inform his faux reality and make it sing with what feels like a deeply honest truth. Carlo Battisti is no longer a college lecturer nor is he an actor. In the confines of this film, he is Umberto Domenico Ferrari.

Although it’s a film dedicated to De Sica’s father, it’s never heavy-handed in its implementation or maudlin in a way to manipulate emotions out of us. The story opens simply with retirement-age marchers protesting in a plaza. They take issue with how low their pensions are especially after having devoted their entire lives to work. Instead of being heard, they are hustled out by local cops in jeeps. They are seen at best as doddering old fools and at worst as a public nuisance.

He must settle instead with taking his dog Flike home to his small domicile. There’s a lovely ordinariness in the full spectrum of his apartment as the camera pans around the room. Umberto settles down to his chair still grumbling about paying rent for such a dump as the young maid gets ready to cut up a chicken.

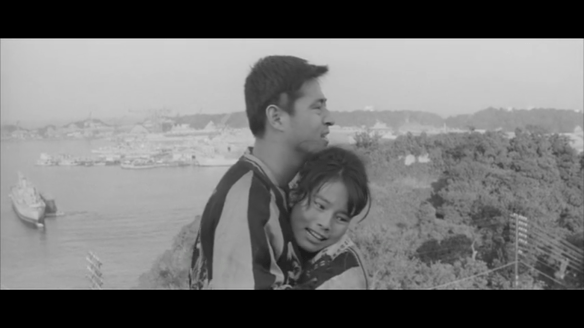

The peppy 15-year-old Maria-Pia Casilio feels perfectly suited for her part like Battisti, and they make a venerable pair. It feels reminiscent of the two co-workers in Ikiru. The disparity in age somehow highlights how they are able to spur one another on, joining their bright-eyed naivete and jaded experience to encourage one another in unknowable ways.

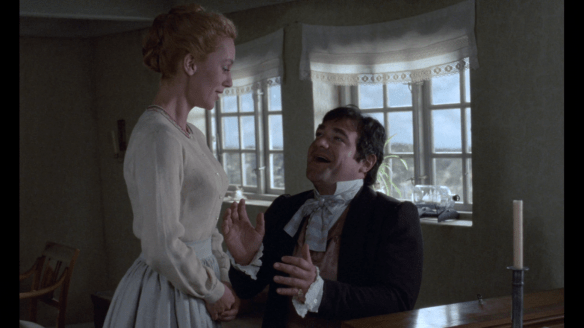

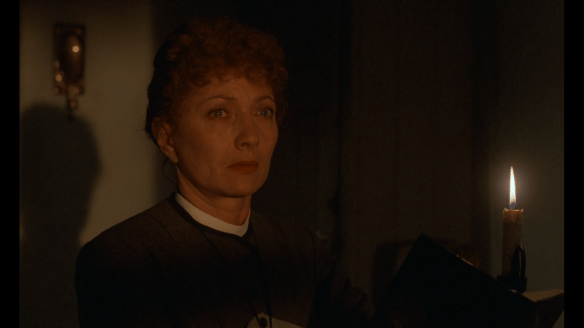

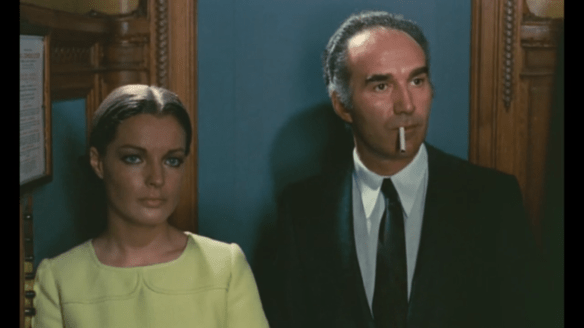

It’s soon apparent his money problems follow him everywhere. His stingy landlady (Lina Gennari) is prepared to evict him by the end of the month if he doesn’t come up with his back rent; she’s making it as difficult for him as possible. It’s very plain she doesn’t what to bargain with him and yet she’s more than willing to make allowances for trysts as long as their money is good.

Umberto is incensed, but he has to manage the best he can, hocking all his belongings while he battles through a fever. If the movie made up of a recurring motif it might be how the old man is systematically belittled and disregarded. The building is getting refurbished with new paint and wallpaper, but the painters have no regard for his space. They have work to do.

A doctor coolly dismisses his tonsillitis because of his age. He’s already lived a decently long life so why bother? Street vendors won’t haggle with him and force him to buy useless stuff that he doesn’t want just to pay a taxi fare. Old work colleagues look at him as a lucky man, free of hassles and living the good life; they fail to notice the signs of his discontent. And finally, there are a husband and wife who mind a household of mutts and strays.

Umberto has ideas of leaving him with a husband and wife who live with a pack of mutts. Again, it’s not stated, but he doesn’t have to. We know this is his final act of love as he dishes out all the money he has left and feigns a trip. It’s all for show, but it would be worth it if Flike was guaranteed a good home.

It’s better than the pound, death in no uncertain terms, but he slowly realizes he cannot bear to do it. It’s not good enough and so he takes his dog away. A little girl’s parents scorn the idea of taking in the cur.

How he knows them and where she came from was only a passing query. Yet again he’s been brutalized. It feels like people are very pointedly rejecting him and he’s helpless. What is he to do?

There are several times throughout the movie it becomes obvious. There’s a glance out a window down to the dizzying cobblestone below. Later Umberto has Flike in a near-chokehold as he disregards the warning bells and totters toward the train tracks. Nothing happens but both instances, first by the direction of our gaze and then by Umberto’s actions, you know he’s thought about doing — ending it all. It would be so easy. But then he thinks of Flike, his best friend, and the one that means more to him than anything.

It never hinges on one singular apex of drama though it does feel like the movie is going increasingly toward the nadir. If I recall The Bicycle Thief — a film with the most crushing of exit points — it’s not simply about poverty at all; it’s about what that does to an individual’s sense of self-worth and dignity. Because De Sica makes us see these people as worthwhile, if only for the mere reason that he takes his time to put them in front of his camera.

However, Umberto D. differs from many of its predecessors because there is no obvious inflection point. We get this full-bodied totally present sense of who he is without a preconceived notion of drama. The picture never goes there, instead, leaning into the sobering sense of desolation and angst.

The fact that De Sica claimed this to be the personal favorite of his film and that it was dedicated to his father seem to be interrelated. I know nothing about the man and if we’ve seen Umberto D. we don’t need to. Not that they’re one and the same; it’s his plight saying so much about how we should treat not only our parents but our elders in general.

I’ve never forgotten that man who came into our classroom because he was right. What a sorry world we live in when the men and women who have served faithfully and put their faith in a system are so rudely cast aside. If I’m to understand this film, it’s not simply a social or political issue, though these play a part; this is about searching out and affirming the worth of other people.

4.5/5 Stars