May 25th, 1945. That’s when The Clock was originally released. To save you doing all the mental calculations V-E Day was on Tuesday, May 8th and the folks at home were ready for the war to be over. So in such an environment, this is hardly a war film and it can’t even claim to be a post-war picture like The Best Years of Our Lives (1946). It’s floating in limbo.

This is the story of a fresh-faced soldier boy in the big city (Robert Walker) constantly craning his neck in awe of skyscrapers and cowering a little bit under the weight of them all. As such he’s constantly being bumped into, like a tourist perpetually lost. From such a moment springs an almost unforgivable meet-cute we can spy from a mile away. She trips over him and loses a heel.

But our stars are winsome and their persons genuine in nature in the days when that was unequivocally so. Corporal Joe Allen (Walker) proves to be to New York City what Mr. Smith was to Washington D.C. He even rides the very same sightseeing bus. He’s also a bit of an idealistic builder not unlike George Bailey.

The soldier and the gal he asks to follow a piece, end up taking a Central Park stroll together followed by a tour of the local art museum, taking a load off, butt up against an Egyptian sphinx. There’s something inherently refreshing about its meandering wanderings through New York City. It gives this illusion of circumstance where there is no clear-cut agenda. In a moment of decision, he goes pell-mell chasing after her bus because he knows something special is onboard and he sets up a date just like that.

Vincente Minnelli is looking out for his heroine as Judy Garland was his own new romantic interest but his camera setups also reflect a stewardship over the contents of the film with his usual array of fluid shots. Far from just taking care of Garland you always get a sense Minnelli is watching out for all his actors with his camera often walking alongside them. She proves to be a fine performer sans singing and although long remembered for Strangers on a Train (1951) and his tumultuous personal life, Robert Walker undoubtedly exudes a naive candor of his own.

It’s always striking how Hollywood was able to cast a certain vision of the every day while reality was oftentimes so different. One aspect of that was the wartime shortages which made shooting on location highly impractical so everything from train stations to exteriors were created on the MGM lot to closely mirror their real-life counterparts and it, for the most part, takes very well. We feel like we are traveling through the big city with a soldier and a gal. At any rate, the city crowds feel realistically suffocating.

But beyond the simple (or not so simple) realm of sound stages and set design it also extends to the actors themselves. Robert Walker who played opposite his wife in the epic home front drama Since You Went Away (1944), had a horrid time getting through the picture as their marriage was on the rocks.

By the time he got to The Clock he had been overtaken by alcohol addiction and Jennifer Jones was all but on the way to marrying executive David O. Selznick. Judy Garland on her part, that shining beacon of traditional Americana was struggling with an addiction of her own and after some creative differences with Fred Zinnemann, she had her soon-to-be husband Vincente Minnelli brought on to revitalize the production.

In these ways, it becomes obvious how there’s almost a conflicting double life going on in front of and behind the camera and yet there’s no doubting that this picture is brimming with sincerity whether partially made up or perfectly simulated. It still works.

You can undoubtedly see the same fascination with the very conversations and interactions that make up a relationship in everyday environments. The walking and talking we do when we share time together. The silly things we get caught up on or pop into our heads on a whim. And yes, there is a bit of Before Sunrise (1995) and Before Sunset (2004) in Minnelli’s picture for those who wish to draw the parallels but the beauty of it is The Clock is obviously not trying to be anything else. It takes simple joy in its story and the characters it holds in its stead.

It’s a film that dares have a scene where our two leads sit in a park, silent for a solitary moment as they listen to the street noise emanating from the city center and breaking into their tranquility. Take another extended sequence where the two lovebirds catch a ride on a midnight milk wagon driven by that perennial favorite James Gleason.

He’s the local milkman waiting impatiently for his request on the late night radio station and intent on some company along the route. But a flat tire puts him out of commission only to bring about another inspired piece of casting. Keenan Wynn as a drunk appears for mere minutes and earns high billing in the picture. It’s worth it. When our stars are allowed to sink into the periphery, the accents of the real world come into focus.

It’s equally true that those are the exact moments where you see the extent of another person’s character. Because it’s not simply the two of you but you get the opportunity to see them in a context with other people and that’s often very telling about who they are. Depending on the perceptions it can make you fall even more in love with someone and seeing as these two individuals help their new friend with his milk run, you can just imagine what it does for their relationship.

As for James Gleason and Lucille Gleason, they make the quintessential cute old couple and that’s because they truly are spinning their wisdom and bickering like only the most steadfast wedded folks do. The last leg of the film is when it goes for drama turning into a literal race against the clock bookended by one of the most distinct courthouse weddings ever captured. But even this picture doesn’t end there. Further still, it sinks back into this odd shadowland between the drama and the happy ending.

We could venture a guess it settles in on a realistic denouement where life isn’t always as we would like it but we can still love people deeply and do not regret the decisions we have made. As we walk off into the crowd with Judy Garland there is little to no regret only a faint hope for a future and assurance in the institution of marriage as something worth pursuing.

They are traditional values and yet, in this context, there’s something comforting about them. Minnelli has spun his magic on us even as the cinematic in its so-called reality slowly drifts away from the Hollywood marital standards of its stars. It’s both an idealized vision and a genuine one.

4/5 Stars

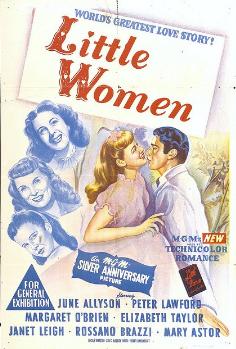

In the recent days, I gained a new appreciation of June Allyson as a screen talent and in her own way she pulls off Jo March quite well though it’s needlessly difficult to begin comparing her with Katharine Hepburn or Winona Ryder.

In the recent days, I gained a new appreciation of June Allyson as a screen talent and in her own way she pulls off Jo March quite well though it’s needlessly difficult to begin comparing her with Katharine Hepburn or Winona Ryder.

We’re all part monsters in our subconscious. ~ Leslie Nielsen as Commander Adams

We’re all part monsters in our subconscious. ~ Leslie Nielsen as Commander Adams Previously, whenever I thought of Elvis and films, my first inclination was to think musical and then secondly because, by some form of osmosis the culture had taught me this, Elvis went with Ann-Margret. In truth, they were astoundingly only ever in this one picture together but what a picture for them to be in. It left an indelible impact on both stars as much as it did their audience.

Previously, whenever I thought of Elvis and films, my first inclination was to think musical and then secondly because, by some form of osmosis the culture had taught me this, Elvis went with Ann-Margret. In truth, they were astoundingly only ever in this one picture together but what a picture for them to be in. It left an indelible impact on both stars as much as it did their audience.

Our introduction to The Mortal Storm feels rather flat. Bright and bland in more ways than one as we become accustomed to our main storyline. Professor Viktor Roth (Frank Morgan) is held in high regard all throughout the community as a prominent lecturer at the local university and beloved by his colleagues and family. The year is 1933 and the Bavarian Alps are still a merry and gay place to live. That’s our understanding early on as the Professor celebrates his 60th birthday with much fanfare and receives a commemorative memento from his class.

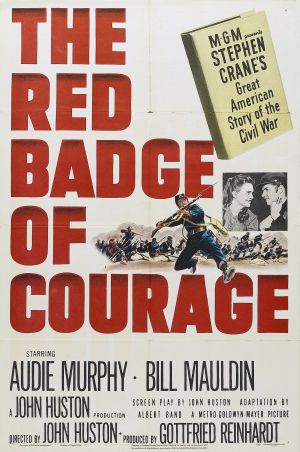

Our introduction to The Mortal Storm feels rather flat. Bright and bland in more ways than one as we become accustomed to our main storyline. Professor Viktor Roth (Frank Morgan) is held in high regard all throughout the community as a prominent lecturer at the local university and beloved by his colleagues and family. The year is 1933 and the Bavarian Alps are still a merry and gay place to live. That’s our understanding early on as the Professor celebrates his 60th birthday with much fanfare and receives a commemorative memento from his class. Stephen Crane’s seminal Civil War novel was made to be gripping film material and although my knowledge of the particulars is limited John Huston’s story while streamlined and truncated feels like a fairly faithful adaptation that even takes some effort to pull passages directly from the original text.

Stephen Crane’s seminal Civil War novel was made to be gripping film material and although my knowledge of the particulars is limited John Huston’s story while streamlined and truncated feels like a fairly faithful adaptation that even takes some effort to pull passages directly from the original text.