Are you always drawn to the loveless and unfriended? ~ Edward Rochester

Are you always drawn to the loveless and unfriended? ~ Edward Rochester

When it’s deserved. ~ Jane Eyre

I can still recall visiting the Bronte Parsonage, marveling at the fact that these sisters were able to have such a lasting impact on the world of literature — a world so often dominated by men at that time — and I simultaneously rued the fact that I had yet to crack open any of their works. Now several years down the road, I still have not opened up Wuthering Heights or Jane Eyre by Emily and Charlotte Bronte and so I can only come into this 20th-century adaptation with certain expectations.

I realize that no film can wholly represent every page of a novel — especially of great length — because in a practical sense it’s simply not theatrically possible. But my hope is that at the very least this version of Jane Eyre maintains the essence of the source material and if nothing else I can revel in the fact that it is a thoroughly engrossing film from director Robert Stevenson.

It feels like some sort of intriguing marriage between Orson Welles’ Mercury Theatre and the recent craze of gothic fiction adaptations — the most noted of course being Hitchcock’s Rebecca only a few years prior — that by some strange happenstance had input from Aldous Huxley. Here we have the ever timid beauty Joan Fontaine starring once more, this time opposite Welles. But the story starts at a much earlier point in the life of Jane Eyre.

Her life is a desolate and horrible affair as we soon find out, due in part to a caustic culture that uses their religion to ostracize others instead of bringing them into the fold of society.

In fact, most of those who hold a Christian belief system are puritanical and more problematic still, hard-hearted. Ironically, there’s no room for grace in the Christian faith that they practice. Foremost among this crowd is Mr. Brocklehurst (Henry Daniel) who runs the Lowood Institution for Girls.

It’s in this very issue revealed early on where the film finds much of its substance. Because thematically all throughout the narrative the audience is forced to grapple with various characters who are subjugated to the fringes of society and for various reasons are labeled as outcasts.

This is how Jane is seen first by her unfeeling aunt (Agnes Moorehead), then by the narrow-minded reverend. They seem absolutely incapable of compassion sitting atop their high horses of proclaimed humility and charity. In reality, they have very little of either to offer. A few do show her kindness including Dr. Rivers (John Sutton) and the cook Bessie (Sarah Allgood) but such behavior is the exception and not the norm.

Still, Jane the very person who has been relegated to a wretched and lesser state is for that very reason ready and willing to reach out to those around her who are treated likewise. The very fact that she has been marginalized allows her to see it in others and be compelled to move toward them when others move away. She cares deeply for the outsider.

The most galvanizing experience involves her closest friend as a young girl (played by a child who still is very unmistakably Elizabeth Taylor). Then as she grows up and chooses to move away from the oppression of her surrogate home, it is the role of a governess in a gothic manor that once more allows her the opportunity to extend her graces to others. First in the form of the precocious ballerina extraordinaire (Margaret O’Brien) and then the brusque but obviously tortured man of the house (Orson Welles).

She sees in him something that runs deeper than the surface. He’s far from a bad man. In fact, she grows to love and cherish him because she sees the good that dwells in his conflicted soul. Burdened as he is with guilt and a past that still haunts him to the present moment. The film exhibits a bit of a love triangle as Rochester invites many guests to his estate among them the well-to-do Blanche Ingram (Hillary Brooke).

But the film pulling from its source material goes a step further still. It digs into the dark recesses, involving itself with the less than pleasant realities, namely an unseen person who hangs over the storyline like a specter. In those very designs, whether they are simply employing the rhythms of Bronte’s book or not, there’s another evident parallel there with the 1940 adaptation of du Maurier’s Rebecca.

Gothic tones matched with an impending sense of foreboding with the demure Fontaine similarly relating the action through voiceover even reading verbatim off the page as if from a diary. And once again it works. While there is no Mrs. Danvers, Welles has the same Shakespearian gravitas of an Olivier that accentuates the very modesty of many of Fontaine’s performances. Their exchanges reflect the sensibilities of the time but furthermore help draw up the very differences of their characters. However, as much as that juxtaposition would seem to draw them apart it even more passionately brings them together.

Some might find this rendition of Jane Eyre too stark, too much of a studio production, even too abrupt, but with Welles and Fontaine opposite each other, it’s a frequently enjoyable gothic romance. As much as gothic romances can possibly be enjoyable.

4/5 Stars

Like the fella says, in Italy for 30 years under the Borgias they had warfare, terror, murder, and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and the Renaissance. In Switzerland they had brotherly love – they had 500 years of democracy and peace, and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.

Like the fella says, in Italy for 30 years under the Borgias they had warfare, terror, murder, and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and the Renaissance. In Switzerland they had brotherly love – they had 500 years of democracy and peace, and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.  Joseph Cotten is surprisingly compelling as the poor, unfortunate stiff and it’s hard not to feel sorry for him in his ignorance because we can relate with him. Alida Valli is striking as the aloof beauty who nevertheless has an unswerving affection for her former love that remains the only joyous thing in her current existence. Then, of course, there’s Orson Welles as the charismatic myth of a man–arguably the most intriguing supporting character there ever was even if it’s mostly thanks to the legend created by those who knew him.

Joseph Cotten is surprisingly compelling as the poor, unfortunate stiff and it’s hard not to feel sorry for him in his ignorance because we can relate with him. Alida Valli is striking as the aloof beauty who nevertheless has an unswerving affection for her former love that remains the only joyous thing in her current existence. Then, of course, there’s Orson Welles as the charismatic myth of a man–arguably the most intriguing supporting character there ever was even if it’s mostly thanks to the legend created by those who knew him. “There live not three good men unhanged in England. And one of them is fat and grows old.”

“There live not three good men unhanged in England. And one of them is fat and grows old.” The triangle with Prince Hal (Keith Baxter) vying for the affection of his father King Henry IV (John Gielgud), while simultaneously holding onto his relationship with Falstaff is an integral element of what this film is digging around at. But there’s so much more there for eager eyes.

The triangle with Prince Hal (Keith Baxter) vying for the affection of his father King Henry IV (John Gielgud), while simultaneously holding onto his relationship with Falstaff is an integral element of what this film is digging around at. But there’s so much more there for eager eyes. And it’s only one high point. Aside from Welles’s towering performance, Jeanne Moreau stands out in her integral role as Doll Tearsheet, the aged knight’s bipolar lover who clings to him faithfully. The cast is rounded out by other notable individuals like John Gielgud, Margaret Rutherford, and Fernando Rey.

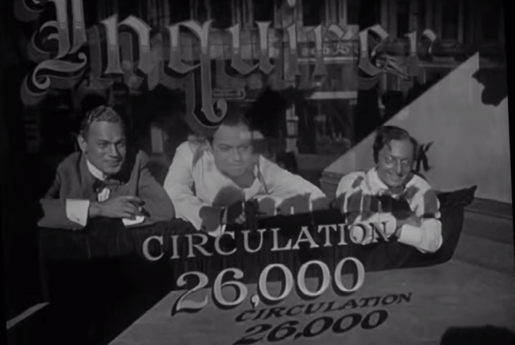

And it’s only one high point. Aside from Welles’s towering performance, Jeanne Moreau stands out in her integral role as Doll Tearsheet, the aged knight’s bipolar lover who clings to him faithfully. The cast is rounded out by other notable individuals like John Gielgud, Margaret Rutherford, and Fernando Rey. Citizen Kane is so often lauded for the simple fact that never before had a director had so much creative control on a project and exercised it in such an unprecedented fashion, especially given the state of affairs in the Hollywood studio system. It’s an enigma, a stunning debut and really an astounding miracle where all things aligned for an instant of so-called perfection.

Citizen Kane is so often lauded for the simple fact that never before had a director had so much creative control on a project and exercised it in such an unprecedented fashion, especially given the state of affairs in the Hollywood studio system. It’s an enigma, a stunning debut and really an astounding miracle where all things aligned for an instant of so-called perfection. At first glance The Trial is a bare-boned parable, feeling gaunt and cavernous with empty sets and even emptier words. Everyone Josef meets talks him in circles, tirelessly — never leading to any significant conclusion, only the next diversion in his journey.

At first glance The Trial is a bare-boned parable, feeling gaunt and cavernous with empty sets and even emptier words. Everyone Josef meets talks him in circles, tirelessly — never leading to any significant conclusion, only the next diversion in his journey. If The Trial is a hodgepodge of talent, with the presence of Americans Orson Welles and Anthony Perkins, international sirens Jeanne Moreau, Elsa Martinelli and Romy Schneider, with European backing and source material from Kafka, then it is a thoroughly intriguing marriage all the same. This film is perhaps the greatest adaptation of the work of Kafka and not due necessarily to its faithfulness to its source material, but because it displays an unmistakably Wellesian vision. The cyclical nature of the legal system pales in comparison with the fascination that comes with watching the continual creativity that is projected up on the screen — this is a hollow dream of a film.

If The Trial is a hodgepodge of talent, with the presence of Americans Orson Welles and Anthony Perkins, international sirens Jeanne Moreau, Elsa Martinelli and Romy Schneider, with European backing and source material from Kafka, then it is a thoroughly intriguing marriage all the same. This film is perhaps the greatest adaptation of the work of Kafka and not due necessarily to its faithfulness to its source material, but because it displays an unmistakably Wellesian vision. The cyclical nature of the legal system pales in comparison with the fascination that comes with watching the continual creativity that is projected up on the screen — this is a hollow dream of a film. It’s the bane of my literary existence, but I must admit that I have never read Joseph Heller’s seminal novel Catch-22. Please refrain from berating me right now, perhaps deservedly so, because at least I have acknowledged my ignorance. True, I can only take Mike Nichol’s adaptation at face value, but given this film, that still seems worthwhile. I’m not condoning my own failures, but this satirical anti-war film does have two feet to stand on.

It’s the bane of my literary existence, but I must admit that I have never read Joseph Heller’s seminal novel Catch-22. Please refrain from berating me right now, perhaps deservedly so, because at least I have acknowledged my ignorance. True, I can only take Mike Nichol’s adaptation at face value, but given this film, that still seems worthwhile. I’m not condoning my own failures, but this satirical anti-war film does have two feet to stand on. The Chaplain (Anthony Perkins) doesn’t feel like a man of the cloth at all, but a nervously subservient trying to carry out his duties. An agitated laundry officer (Bob Newhart) gets arbitrarily promoted to Squadron Commander, and he ducks out whenever duty calls. Finally, the Chief Surgeon (Jack Gilford) has no power to get Yossarian sent home because as he explains, Yossarian “would be crazy to fly more missions and sane if he didn’t, but if he was sane he’d have to fly them. If he flew them he was crazy and didn’t have to; but if he didn’t, he was sane and had to.” This is the mind-bending logic at the core of Catch-22, and it continues to manifest itself over and over again until it is simply too much. It’s a vicious cycle you can never beat.

The Chaplain (Anthony Perkins) doesn’t feel like a man of the cloth at all, but a nervously subservient trying to carry out his duties. An agitated laundry officer (Bob Newhart) gets arbitrarily promoted to Squadron Commander, and he ducks out whenever duty calls. Finally, the Chief Surgeon (Jack Gilford) has no power to get Yossarian sent home because as he explains, Yossarian “would be crazy to fly more missions and sane if he didn’t, but if he was sane he’d have to fly them. If he flew them he was crazy and didn’t have to; but if he didn’t, he was sane and had to.” This is the mind-bending logic at the core of Catch-22, and it continues to manifest itself over and over again until it is simply too much. It’s a vicious cycle you can never beat. But the tonal shift of Catch-22 is important to note because while it can remain absurdly funny for some time, there is a point of no return. Yossarian constantly relives the moments he watched his young comrade die, and Nately (Art Garfunkel) ends up being killed by his own side. It’s a haunting turn and by the second half, the film is almost hollow. But we are left with one giant aerial shot that quickly pulls away from a flailing Yossarian as he tries to feebly escape this insanity in a flimsy lifeboat headed for Sweden. It’s the final exclamation point in this farcical tale.

But the tonal shift of Catch-22 is important to note because while it can remain absurdly funny for some time, there is a point of no return. Yossarian constantly relives the moments he watched his young comrade die, and Nately (Art Garfunkel) ends up being killed by his own side. It’s a haunting turn and by the second half, the film is almost hollow. But we are left with one giant aerial shot that quickly pulls away from a flailing Yossarian as he tries to feebly escape this insanity in a flimsy lifeboat headed for Sweden. It’s the final exclamation point in this farcical tale.