“Who are you, God? Didn’t you ever make a mistake?” – Cathy O’Donnell as Susan Carmichael

Counselor at Law (1933) was an early William Wyler film from the 1930s that shares some cursory similarities with this feature. Along those lines, Detective Story proves to be an exploration into the life of a cop much as the earlier film allowed us to look through the keyhole at the life of a lawyer (John Barrymore). Fundamentally they also both provide the same cross-section of society with Wyler navigating the space in such a way to tie the threads together while keeping things engaging.

Detective Story proves to be a stage play and a morality play in one fell swoop and that is decidedly both good and bad. It’s true that the crossroads of so many films and talents meet here and all share a room together.

There’s another fiery role for “Mr. Instensity” himself Kirk Douglas as Jim McLeod, a man who strives to rid the streets of criminals and put them where they belong: The electric chair. He wants to be judge, jury, and executioner if at all possible. His all-out war on crime can be traced back to his lousy father. Ever since those days, he’s vowed to be everything his old man never was — not tolerating any kind of infraction of the law. It’s a thoroughly intense portrayal though it jumps off the emotional deep end a few times too often.

It’s his supporting cast that steadies him and guides the film toward something more authentic and attainable. William Bendix was potentially slated for a reunion with Alan Ladd before Douglas ultimately took the role. However, he trades out his image as a heavy for a policeman with a decent dose of humanity.

Frank Faylen is the acting desk clerk who fields all the incoming calls that come his way. Meanwhile, Lee Grant is a skittish young purse snatcher who winds up at headquarters for her first offense. Cathy O’Donnell (wife of screenwriter Robert Wyler) plays her always immediately likable ingenue role as the young woman trying to bail out her childhood friend on a charge of theft.

There are a number of others including journeymen cops, journalists, and four-time losers and then there’s McLeod’s wife Mary (Eleanor Parker). I’m not sure what to evaluate Eleanor Parker on but in the recent months, I have gained an appreciation for the fact that, good or bad, she will fearlessly commit to a role and pour her all into it. She owns a very eclectic body of work as well but Detective Story sees her succumbing to histrionics much like her onscreen husband.

Because at its best Detective Story is a slice-of-life drama that gives us insight into humanity much as Counselor at Law (1933) did. But this picture is high on the dramatics and whether or not they are completely believable is up for contention.

It’s also a fairly frank picture at that — at least for its day — though it does point out the duplicity that’s so blatantly clear. Here a taboo is utilized as the fodder for melodrama as something so despicable. Yet in the heart of Hollywood itself, there were undoubtedly many women who did similar covering up jobs to save their reputations.

The Hays Code could try and keep taboos under raps but in doing so they were ignoring an unfortunate reality. It is necessary to remove the shrouds and let these things live on in the light.

But far from seeing this film with our enlightened postmodern sensibilities and condemning it for making such a frank subject seem sullied and unseemly, I would contend that this picture leaves me melancholy. Not for the reasons you might expect either.

I feel sorry for women ostracized and labeled as “tramps” like Mary is. I’m ashamed that there is a standard that everything must be good and pure. There is no room for grace. It’s this hypocritical nature that’s blatantly obvious in McLeod with the bitter irony coming to fruition. He became the very person that he was striving never to become.

The depressing depths of the drama suffocate any chance of a laugh by the film’s latter half and so while I’m all for fatalistic even tragic denouements in the right context, this film is so utterly discouraging and it has nothing to do with desiring a happy ending. It’s more closely related to the lens in which the film seems to use. There’s no integrity left in humanity. A world where beating hearts of flesh have been transformed into hearts of stone. That’s a very dark world to try and reconcile with.

Worst yet it does try by heaping on more drama and last minutes heroics to right all the wrongs in a matter of seconds. So we lose on two accounts. The picture doesn’t have the guts enough to dig into its disconsolate inclinations and still for almost its entire runtime it’s focused on those precise conflicts making it supremely difficult to enjoy Detective Story as much as we could have.

3.5/5 Stars

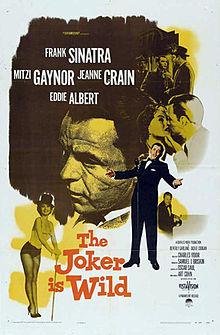

It required quite the journey to make it to this film, starting out with a different joker entirely. My introduction to comedian Joe E. Lewis happened because of the late, great Jerry Lewis. Revisiting his life and work I made the discovery that the comedian changed his name to avoid confusion with two men. First, Joe Louis the stellar boxer of the 1930s and then Joe E. Lewis the comedian.

It required quite the journey to make it to this film, starting out with a different joker entirely. My introduction to comedian Joe E. Lewis happened because of the late, great Jerry Lewis. Revisiting his life and work I made the discovery that the comedian changed his name to avoid confusion with two men. First, Joe Louis the stellar boxer of the 1930s and then Joe E. Lewis the comedian.