George Stevens is only one among a plethora of filmmakers who came back from WWII changed. He had seen a great deal of the world’s ugliness — Dachau Concentration Camp for instance — and as a result, the films he made thereafter were more mature ruminations on humanity at-large. Adapted from Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy and a subsequent play, A Place in the Sun is one of those pictures crafted in the wake of such historical change.

There’s no doubt that this is Hollywood melodrama backed by a raging score from Franz Waxman but this is no less, high powered high-class stuff. It’s augmented by gorgeous black and white imagery that reaches pitch-black tones and still manages to make Lake Tahoe into a scintillating getaway. Meanwhile, the camera captures the action with elegant movements, sashaying through space, at times nearly imperceptible to the eye. Though admittedly the film’s stature as a social commentary is less interesting now than it probably would have been in its day. Still, we can’t have everything now, can we?

Montgomery Clift is often forgotten in the fray of powerhouse actors but the line can easily be traced from his intense performances to the work of Brando and Dean which would also sprout up in the 50s. Though that same intensity is there, it never feels like he’s trying to sell us a gimmick or a method. He’s simply trying to provide a lens to see a bit more clearly the intricacies of an individual, in this case, one George Eastman. It manages to be a profound and at times an agonizing performance.

Of course, Elizabeth Taylor is exquisite in every frame as always but her bright-eyed sincerity is equally arresting. She feels perfectly made for the role of Angela Vickers and seamlessly transitions into more adult fare with A Place in the Sun, standing tall alongside Clift, destined to make them one of the great romantic pairings of the 1950s. She supposedly said that she finally felt less like a puppet and more like an actress after this film. It shows.

Still, though given a thankless role at times, Shelley Winters is equally important because, in her simpler, humbler way, she reflects how quickly a man can change. She’s not a bad person at all, just a frail, even helpless one who feels like she has very few people in the world to hold onto. George proves to be a comparable companion until he unwittingly finds himself running in different circles and that’s where the tension begins.

I look at George Eastman and see the same drive for recognition, power, and wealth in many of us, those desires that oftentimes can be our undoing because they turn out to be meaningless. The irony is that his intentions never seem malicious but he is undermined by something. He quickly sinks into this double life. At first, he was simply happy to have a job and some companionship. His desires were simple. But slowly, as he found himself rising in the ranks of the Eastman company and getting more recognition, he couldn’t help but want more. Are these impulses bad? Not in the least, but they led him to some pretty rocky soil.

The scene that stands out in my mind could seem fairly mundane. But Stevens maintains a fairly long shot that’s peering through Eastman’s living room and we can see into the next room over as he is on the phone. It feels like minutes go by and Stevens fearlessly never cuts the sequence. The first call is from Alice which he takes.

But the second comes from Angela and at that point, we know that things have changed. It’s set up the dilemma. He genuinely loves Angela and wishes to be with her and to be a part of her life. Yet for that to come to fruition he must do something about the other girl. Alice won’t disappear. It’s funny how someone who you used to appreciate so dearly now feels like a burden. To her credit, we feel sorry for Winters’ character without question.

In fact, the film succeeds along those lines. We pity her for the sorrowful position she is placed in — essentially abandoned by George. And even in her frivolity and opulence, there’s a candidness to Angela that makes us want to root for her and that allows us to simultaneously pity her because she has no idea of George’s other life. If there is anyone to lash out against it is George Eastman himself and still even in that regard, Montgomery Clift reveals the full gamut of this tortured man so even if we are hesitant to feel sorry for him, he does open us up even with a tinge of compassion.

But the muddled morality is complicated by the fact that Clift’s character has a sense of remorse. Surely he cannot be all bad based on what Vickers saw in him? His capacity to love and be tender is evident. Still, that is not enough to keep him from going on trial and the film’s final third takes place, for the majority, in a courtroom. The district attorney is played by Raymond Burr, who might well be in a dry run for Perry Mason and he comes at Eastman with all the fervor he can muster to convict him in his lies. Even in these moments, we must fall back on George’s inner conflict, his capability to love others, and his intentions for love.

If A Place in the Sun gets too preachy or succumbs too much to Hollywood’s stirringly romantic tendencies, it still might be one of the finest examples of such a film. Front and center are two phenomenal stars and Stevens films their euphoric romance with a meticulous eye, catching them in particular moments, with close-ups, and such angles that we are constantly aware of their intimacy.

As much as Eastman is looking for his place in the sun, and he could spend hours just sitting with Angela soaking in the sun’s rays (not many would blame him), it’s just as true that there is nothing new under the sun. That’s what we’re left with. Mankind is still distracted by many things. Oftentimes they are good things, but we make them ultimate things, and they wreak havoc on our lives. Meaningless, meaningless, everything is meaningless under the sun. But that doesn’t keep us from wanting to bathe in its tantalizing warmth any less. That’s part of the American Tragedy.

4.5/5 Stars

Again, I must confess that I have not read yet another revered American Classic. I have not read A Farewell to Arms…But from the admittedly minor things I know about Hemingway’s prose and general tone, this film adaptation is certainly not a perfectly faithful translation of its source material. Not by any stretch of the imagination.

Again, I must confess that I have not read yet another revered American Classic. I have not read A Farewell to Arms…But from the admittedly minor things I know about Hemingway’s prose and general tone, this film adaptation is certainly not a perfectly faithful translation of its source material. Not by any stretch of the imagination.

Before the exoticism of Casablanca, Algiers, or even Road to Morroco, there was Josef Von Sternberg’s just plain Morocco but it’s hardly a run-of-the-mill romance. Far from it.

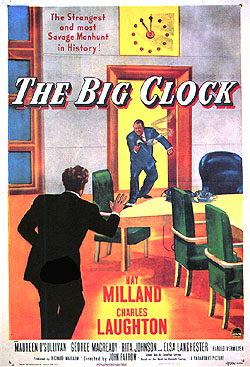

Before the exoticism of Casablanca, Algiers, or even Road to Morroco, there was Josef Von Sternberg’s just plain Morocco but it’s hardly a run-of-the-mill romance. Far from it. With its rather dreary title aside, The Big Clock is actually an enjoyable thriller that works like well-oiled clockwork. It’s true that oftentimes the most relatable noir heroes are not the hardboiled detectives, although they might be tougher and grittier, it’s the hapless everymen who we can more easily empathize with. Bogart, Powell, and Mitchum are great but sometimes it’s equally enjoyable to have someone who doesn’t quite fit the elusive parameters that we unwittingly draw up for film-noir. Ray Milland is a handsome actor and he was at home in both screwball comedies (Easy Living) and biting drama (The Lost Weekend). He’s not quite what you would describe as a prototypical noir hero.

With its rather dreary title aside, The Big Clock is actually an enjoyable thriller that works like well-oiled clockwork. It’s true that oftentimes the most relatable noir heroes are not the hardboiled detectives, although they might be tougher and grittier, it’s the hapless everymen who we can more easily empathize with. Bogart, Powell, and Mitchum are great but sometimes it’s equally enjoyable to have someone who doesn’t quite fit the elusive parameters that we unwittingly draw up for film-noir. Ray Milland is a handsome actor and he was at home in both screwball comedies (Easy Living) and biting drama (The Lost Weekend). He’s not quite what you would describe as a prototypical noir hero. Soldiers returning home from war is a recurring theme in films such as The Best Years of Our Lives and Act of Violence and given the circumstances it makes sense. This was the reality. Men returning home from war as heroes. But even heroes have to re-acclimate to the world they left behind.

Soldiers returning home from war is a recurring theme in films such as The Best Years of Our Lives and Act of Violence and given the circumstances it makes sense. This was the reality. Men returning home from war as heroes. But even heroes have to re-acclimate to the world they left behind. With Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon making a splash just the year before and giving a big leg up to its star Humphrey Bogart as well as its director John Huston, it’s no surprise that another such film would be in the works to capitalize on the success. This time it was based on Hammett’s novel The Glass Key and it would actually be a remake of a previous film from the 30s starring George Raft.

With Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon making a splash just the year before and giving a big leg up to its star Humphrey Bogart as well as its director John Huston, it’s no surprise that another such film would be in the works to capitalize on the success. This time it was based on Hammett’s novel The Glass Key and it would actually be a remake of a previous film from the 30s starring George Raft.