This is the Introduction to a new column called AFI Corner for film fans who want to get to know The American Film Institute’s 100 Films lists. It’s in concurrence with #AFIMovieClub and the 10th anniversary of becoming a classic movie fan myself. Thanks for reading.

Always in the back of my mind, I had the idea of trying to write a book or compendium on how I got into movies. If you couldn’t guess already, the highly original title of said book was to be 2010: My Film Odyssey (or some derivative).

Well, it’s never gotten off the ground and probably for good reason. The world rejoices. Who would want to read a poorly edited monolith like that? After all, I’m hardly the Stanley Kubrick of the written word. However, in the same breath, 4 Star Films would have never existed without that year and these lists.

It was in 2010 where I began to take a genuine interest in classic cinema. It really was an odyssey born out of curiosity and my own ignorance about movies. I wasn’t exactly an avid moviegoer in those days.

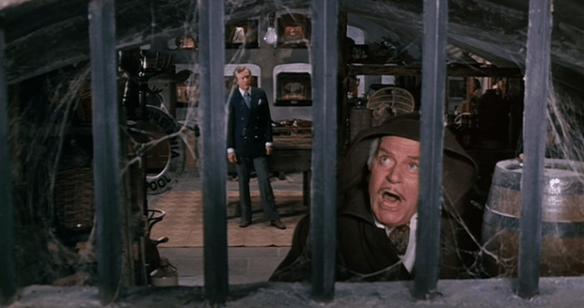

But a family vacation introduced me to TCM (my family never had cable), and I got to see a handful of respected classics. 12 Angry Men (#87), To Kill a Mockingbird (#25), and It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (#40 Laughs) among them. Seeing Mt. Rushmore and Devil’s Monument in the flesh, meant I rushed to my local library when I got home, so I could see North by Northwest (#55) and Close Encounters of The Third Kind (#64 Original).

From there, the details are a bit murky. Somehow I came across the American Film Institute’s lists online, the two flagship editions being released in 1998 and 2007 respectively. I was too ignorant to know how much dialogue (and controversy) came with the unveiling of these lists.

All I had was my curiosity and a desire to see more. When I started, I did my due diligence and checked off a whopping 12 out of 100 back in 2010! And if you’ll notice, almost half of the movies were ones I watched that very same summer for the first time.

So I built up some steam and started taking to the list. I took numerous more trips to the library. Had family members and acquaintances all check their progress on the well-worn paper copies I had so I could match their progress. It was evident I was still a movie novice. But I was learning.

Before I get ahead of myself, I should point out this blog came out of the handwritten notebooks of “reviews” I used to keep. After almost every movie I watched, I had a desire to try and write something down, not only as a record of what I had viewed but also to give it some meaning. I didn’t want it to be a mindless endeavor. I wanted to be invested.

Looking back, I laugh. The writing is stunted and formulaic. It’s more plot summary, and there are very few original ideas, but, again, I was learning — growing as a movie lover and a writer.

I’m not sure how this column will evolve, but I would love to share some of those reviews, many of them buried somewhere on this very blog, and then provide some commentary on them based on the movies and my own personal experiences with them.

Because while my life stage and location have changed quite a lot in the last decade, the movies have remained a constant. What I bring to them anew is what’s so enjoyable with every rewatch.

If I was a true raconteur I would have spun a better tale about my film odyssey. That’s part of the reason my magnum opus never materialized. Instead, I’ll leave you with this. I never actually completed any of the AFI lists outright. As of last year, I have seen 99 of 100 titles from AFI’s 100 Years…100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition)!

Yeah, in 10 years I went from 12 to 99 (The one title I haven’t seen is The Deer Hunter, I know, I know). It doesn’t sound that amazing. However, this fails to count all the countless digressions and sidetracks carrying me through all the nooks and crannies of cinema. And while I might get around to watching #100 someday, I’m actually fine not having finished.

For anyone reading this, with aspirations of going through this list or something similar, I think it’s a reminder that the journey is not just about completion. There’s something to be said for setting goals (even a dubious one like watching more movies) and then going out and enjoying the experience. I can say resolutely this hobby has given me a great deal of joy, and it continues to do so even as it increases in leaps and bounds.

I hope you join me in the AFI Corner to explore more of these lists. I also hope it’s a reminder that something like these compilations is innately flawed, but they are not an end; instead, they’re a beginning. At least that’s what they were for me, and they can be for all of us. A beginning of community, conversation, and connection. Please join me!

How many movies have you seen from AFI’s 100 Years…100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition)?

How did you get started watching classic movies?

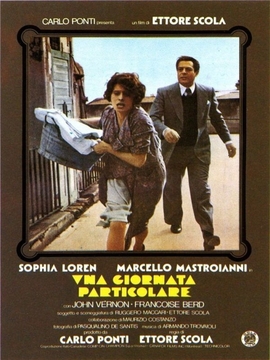

The film opens with newsreel footage delivered to us in an undoctored format effectively presenting us a view into the past. It is the momentous (some would say fateful) day Adolf Hitler made his triumphant visit to see Benito Mussolini in Italy.

The film opens with newsreel footage delivered to us in an undoctored format effectively presenting us a view into the past. It is the momentous (some would say fateful) day Adolf Hitler made his triumphant visit to see Benito Mussolini in Italy.