Barry Sullivan has an absolute field day as a homicide cop, Lt. Collier Bonnabel, with very calculated methods of getting to the root of every crime. Whether it comes by pushing, cajoling, romancing, tricking, or flattering — he’ll do whatever is necessary. What matters to him is to keep stretching them because everyone has a breaking point. You just have to know how to work them so they slip up.

Barry Sullivan has an absolute field day as a homicide cop, Lt. Collier Bonnabel, with very calculated methods of getting to the root of every crime. Whether it comes by pushing, cajoling, romancing, tricking, or flattering — he’ll do whatever is necessary. What matters to him is to keep stretching them because everyone has a breaking point. You just have to know how to work them so they slip up.

It’s fitting because he remains our narrator throughout this entire story. Between his fedora and voiceover narration, Tension easily earns the moniker of film noir. He picks up the story at Coast-to-Coast all-night drugstore in Culver City where the bookish Warren Quimby (Richard Basehart) maintains an unsatisfying but well-paying gig as manager.

His only reason for holding onto the job is not only security but it’s the only way to try and keep his girl (Audrey Totter). Because she’s a real horror — dissatisfied with the middling life he can give her — and constantly batting her eyes at anyone who gives her the time of day.

Quimby is such a passive and nervous husband; he’s always deathly afraid to walk into his room above the drugstore at night for fear the bed will be empty and she won’t be there waiting for him. You see, his entire worth and aspiration for a middle-class lifestyle are maintained through her. And yet when she scoffs at his attempts to buy them a house in the suburbs; it’s a rude awakening.

It turns out it doesn’t matter. She finds someone else and packs her bags. What follows is a sudden departure to shack up with the substantially wealthier Barney Deager. You see the same conundrum from The Best Years of Our Lives. They were youthful and on the high of WWII patriotism, but now settling into the status quo, he’s not as cute or funny as he used to be in San Diego. Everyday tedium is no fun for a girl like Claire.

Audrey Totter is easily a standout, and she even gets some saucy music to introduce her, and the coda proceeds to follow her into just about every room. She’s almost in the mold of Gloria Grahame — another iconic femme fatale — except her eyes are more bitter, even severe. They burn through just about everyone.

Warren makes his way to the beach and has a confrontation with her brawny boyfriend, but what is an unassertive guy like him (now with broken glasses) supposed to do in the face of such an affront? His options seem hopelessly few. It leads to a needed trip to the eye doctor for new spectacles, and he reluctantly leaves with the year’s newest invention — hard contact lenses.

His soda-jerk buddy behind the counter plants the other seed. It drives him to murder. Quimby then gains a whole new perspective, the doctor even touts that he with be an entirely different person, in the most literal sense; he takes on a new name as Paul Sothern. His entire temperament and level of confidence changes. It’s humanly unbelievable and all because of an optometrist. I should have gotten contacts sooner.

The newfound man sets up a residence in Westwood to put his plans in motion. He now has a cool, calculated doppelganger for the perfect crime, available to him at a moment’s notice.

Here we have the most roundabout and, dare we say, ludicrous way to premeditate and perfect a murder. Back in the days when taking on a new identity was a breeze. Erasing and vanishing was a matter of covering up a few loose ends and not leaving a forwarding address.

Basehart could easily be the father of Ryan O’Neal in What’s Up Doc? While not necessarily a taxing role, he is called on to play two characters as he plays opposite two very different women. Cyd Charisse is the sweet and shapely photographer who falls for Paul Sothern, despite knowing so little about him. She is oblivious to his double life, but it doesn’t seem to matter.

Still, as is the case in many film noir, the very overt foils are created and Tension extends them even further. The protagonist has a choice between two women and with them two distinct lives. One is represented by the decadent yet fractured China doll, the blonde spider woman who will not release him from her web.

Then there’s the simpler, sweeter pipe cleaner doll, the brunette good girl who is almost angelic in nature and totally available to help the hero realize their happy ending, which remains in constant jeopardy the entirety of the film.

The wrinkle that really spoils it is when Claire slinks back into his life once more, and he is implicated in a murder. All of a sudden the alternate reality he started carving out for himself is altogether finished. Sothern is quashed and Quimby is suffocating in a life he assumed would be gone forever.

The cops must come into the equation now, asking questions, poking around, and pressing on all the sore spots in hopes someone will break. All character logic aside, the picture does ascribe to a certain amount of tautness suggested in its name, but so could any number of movies — even John Berry’s next film He Ran All The Way.

But I found myself enjoying its contrivances more and more with time. Because each twist of the corkscrew made for another pleasure. Barry Sullivan takes great relish leaning on everyone. William Conrad, for once, is on the right side of the law and still gets to play a gruff character.

However, it is his partner who sets up some very convenient and slightly awkward interactions on a hunch. Quimby is forced to interact with his girl from another life as if it was just a piece of pure happenstance. Then, Claire and the purported “other woman” are somehow pulled together accidentally to churn up a little jealousy.

Bonnabel is like Columbo at his most nefarious, except slightly more conniving and less scruffily endearing. He nabs the dame because, being conveniently trapped in a lie, she confesses. Unlike most Columbo villains, she struts out as defiantly as ever. There’s no recompense or sense of somber civility. With the way she was going before, why bother? Thankfully Totter’s performance is not compromised; she remains icy to the end.

3.5/5 Stars

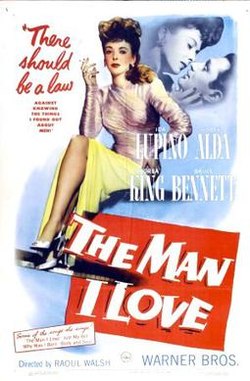

It feels like we might have the courtesy of a bit of Gershwin masquerading under the cloak of noir. We find ourselves at a hole-in-the-wall jazz joint after hours. Club 39 feels free and easy with an intimate jam sesh. Petey Brown (Ida Lupino) is having fun with a rendition of “The Man I Love.”

It feels like we might have the courtesy of a bit of Gershwin masquerading under the cloak of noir. We find ourselves at a hole-in-the-wall jazz joint after hours. Club 39 feels free and easy with an intimate jam sesh. Petey Brown (Ida Lupino) is having fun with a rendition of “The Man I Love.” Of the plethora of returning G.I. films and film noirs, this one reflects their fears most overtly and for this very reason, it might be generally the most forgotten today. That and the assembly of a lower-tier cast. Most of these names have been lost to time.

Of the plethora of returning G.I. films and film noirs, this one reflects their fears most overtly and for this very reason, it might be generally the most forgotten today. That and the assembly of a lower-tier cast. Most of these names have been lost to time.