Andrei Tarkovsky has already left such an indelible impression on me even after only seeing a couple of his films. This already makes it very easy to place him atop that ever fluctuating, never quite established, constantly quarreled over, list of the greatest filmmakers of all time. He’s subsequently one of the members of the fraternity with the least recognition; the key is visibility or lack thereof. Because once you see his work, even if it doesn’t completely speak to you, something is released that’s all its own with a singular vision and the unmistakable brush strokes of an auteur.

There has never been a film more fluid and uninhibited in the distillation of memory than Mirror as it slowly slaloms between the past and the present, enigmatic dreamlike movements with unexplained conversations and encounters, spliced together with bits of wartime newsreels and spoken poetry.

In order to even attempt to ingest any of this rumination at all, there’s a near vital necessity to shed all the traditional forms and languages that you have been taught by years of Hollywood moviegoing.

Not that they are completely excised from Mirror but it’s never driven by logical narrative cause and effect. Rather it’s driven by emotion, rhythm, and feeling — what feels intuitive and looks most pleasing to the eye.

It’s precisely the film that some years ago might have been maddening to me. Because I couldn’t make sense of every delineation culminating in a perfectly cohesive, fully articulated thesis, at least in my mind’s eye. It’s far too esoteric for this to happen. But this unencumbered nature is also rather freeing. There’s no set agenda so as the audience you are given liberty to just let the director take you where he will.

To its core, Mirror gives hints of a very personal picture for Tarkovsky as it memorializes and canonizes pasts memories and shards of Soviet history. Because they are tied together more than they are separate entities. And yet, as much as it recalls reality, Mirror is just what it claims to be. It is a reflection. Where the world is shown in the way that we often perceive it.

The jumbled and perplexing threads of dreams, recollections, conversations, both past and present. Childhood and adulthood, our naivete and our current jaded cynicism, intermingled in the cauldron of the human psyche. Back and forth. Back and forth. Again and again.

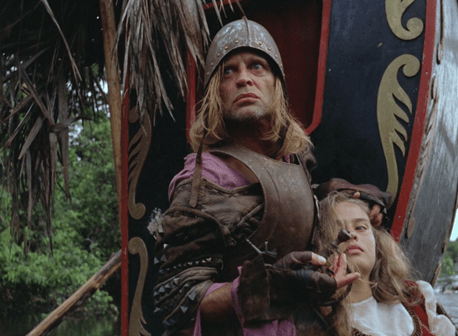

Because what we watch is not simply about one individual. As with any life, it’s interconnected with others around it. A woman (Margarita Terekhova) sitting on a fence post during the war years in an interchange with a doctor. In the present, Alexei, our generally unseen protagonist, converses with his mother over the phone. We peer into the printing press where she worked as a proofreader. Rushing about searching for a mistake she purportedly made. Regardless, it hardly matters.

In the present, Alexei quarrels with his estranged wife on how to handle their son Ignat. The fact that his wife is also played by Terekhova is more of a blessing than a curse. In a passing remark, he notes how much she looks like his mother did and it’s true that she is one of the connecting points. Even as she embodies two different people, the performance ties together the two periods of the film. Visually she is the same and that undoubtedly has resonance to Tarkovsky.

As the film cycles through its various time frames so do the spectrums of the palette. The color sequences have a remarkably lovely hue where the greens seem especially soft and pleasant as if every shot is bathed in sunlight. It’s mingled with the black and white imagery as the story echoes back and forth, past and present, between different shades and coloring. But whereas these alterations often provide some kind of cinematic shorthand to denote a change in time, from everything I can gather, Tarkovsky seems to be working beyond that.

Because there are scenes set in the past that are color, ones in the so-called present that are monochrome, and vice versa. It’s yet another level of weaving serving a higher purpose than merely a narrative one. If I knew more about musical composition I might easily make the claim Mirror is arranged thus — the cadence relying more on form than typical cinematic structure.

That and we have Tarkovsky’s long takes (though not as long as some) married with his roving camera that nevertheless remains still when it chooses to. The falling cascades of rain are almost otherworldly in their spiraling elegance. The wind ripping through the trees a force unlike any other though we’ve no doubt seen the very same thing innumerable times. Fires blaze like eternal flames. Figures lie suspended in the air, isolated in time and space. Each new unfolding is ripe for some kind of revelation.

We also might think our subjects to be an irreligious people but maybe they still yearn for a spirituality of some kind. I’m reminded of one moment in particular when, head in her hands, the wife asks who it was who saw a burning bush and then she notes that she wishes that kind of sign would come to her. If there is a God or any type of spiritual world, the silence is unappreciated.

I recall hearing a quote from the luminary director Ingmar Bergman. He asserted the following, “Tarkovsky for me is the greatest, the one who invented a new language, true to the nature of film, as it captures life as a reflection, life as a dream.”

The words are striking to me because you could easily argue Bergman’s films also had such an ethereal even refractive quality. Look no further than Through a Glass Darkly (1961) or Persona (1966) and this is overwhelmingly evident. And yet he considers Tarkovsky the greatest.

This isn’t the time or place to quibble over the validity of the statement. But it seems safe to acknowledge the effusive praise the Soviet auteur has earned for how he dares play with celluloid threads and orchestrate his shots in ingenious ways. He exhibits how malleable the medium can be as an art form while never quite losing its human core.

4.5/5 Stars

Though it’s easy to be a proponent of

Though it’s easy to be a proponent of

“He will be your true Christian: ready to turn the other cheek, ready to be crucified rather than crucify” ~ Minister of The Interior

“He will be your true Christian: ready to turn the other cheek, ready to be crucified rather than crucify” ~ Minister of The Interior Watching films with French treasure Mr. Hulot (Jacques Tati) is a wonderful experience because, in some respects, it feels like he brings out the child in me. And if history is any indication — I’m not the only one — others feel this sensation too.

Watching films with French treasure Mr. Hulot (Jacques Tati) is a wonderful experience because, in some respects, it feels like he brings out the child in me. And if history is any indication — I’m not the only one — others feel this sensation too. “You can’t just do anything at all and then say ‘forgive me!’ You haven’t changed a bit.” ~ Colette

“You can’t just do anything at all and then say ‘forgive me!’ You haven’t changed a bit.” ~ Colette Antoine Doinel is a character who thinks only in the cinematic and it is true that he often functions in a bit of a faux-reality. He seems normal but never quite is. He seems charismatic but we are never won over by him completely. Still, we watch the unfoldings of his story rather attentively.

Antoine Doinel is a character who thinks only in the cinematic and it is true that he often functions in a bit of a faux-reality. He seems normal but never quite is. He seems charismatic but we are never won over by him completely. Still, we watch the unfoldings of his story rather attentively.