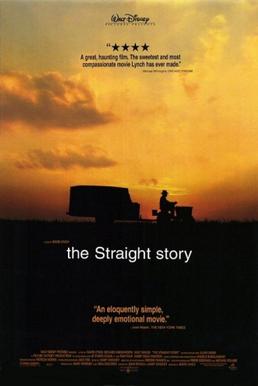

The Straight Story is based on the real-life journey of one Alvin Straight to visit his brother, who suffered a stroke. What makes it extraordinary is that he lived hundreds of miles away, and Straight made the journey on his John Deere lawn mower, going about 5 mph!

The Straight Story is based on the real-life journey of one Alvin Straight to visit his brother, who suffered a stroke. What makes it extraordinary is that he lived hundreds of miles away, and Straight made the journey on his John Deere lawn mower, going about 5 mph!

The material doesn’t immediately scream David Lynch, a man who has left his mark with more bemusing visions of Middle America. Still, in keeping with the story’s ethos, Lynch taps into his midwestern roots in the most charming and straightforward manner.

There is a sense that The Straight Story was a movie out of a different era and even a different century. Whereas now even our eldest geriatrics interface with smartphones, have high-speed internet at their fingertips, and any number of technical marvels, there was a time, maybe 20 or 30 years ago, when men like Alvin Straight reached back into bygone generations.

Alvin can barely see and walks with the assistance of a cane, but he’s obstinate. He was a sniper during WWII. Eats franks by the campfire and always has his cigars handy for a puff or two in the evening as he ponders the stars. His wife, who’s gone now, bore 7 children, and he still lives with one of them, his grown daughter (Sissy Spacek). I won’t say people of his ilk don’t exist anymore, but as we get more and more modernized, it seems less and less commonplace.

There’s a sense of the late ’90s about the movie that I appreciate because I was alive then, albeit very young, on the cusp of the possibilities of a new millennium. The year prior, I traveled with my family across the very same Midwest, though we used a much more luxurious automobile (I had only minor experiences in Iowa with tractors and other implements that felt completely foreign to a California kid). For Alvin Straight, these were his lifeblood as common to him as the water he drinks and the air he breathes.

He gives a glimpse into his own life on his parents’ farm, where he and his brother learned what hard work was as they turned daily chores and tasks necessary for their survival into games that they could play even as they looked up at the stars at night, dreaming about what might be out there.

Time and disagreements soured their relationship, so now, as they stand old and gray, they’re estranged from one another. You understand how it happens. Their generation was not always the greatest at expressing themselves or sharing their emotions. Still, we know they are present, and the fact that Alvin willfully makes this trip shows how deep the bonds of brotherhood go. He speaks through actions.

The film’s boldest and most valuable asset is its sense of time. It is pregnant with silence and comfortable with slowness out of necessity. It goes at the kind of languid pace that’s necessitated by the whole premise of Alvin’s journey from the very beginning. That tractor’s not going to sprout extra engines and zoom forward. The journey is the essence of incremental progress toward an inevitable end.

Like Pilgrim’s Progress, there’s a process to the journey, and it’s made up of all of these various interactions. Each one along the road feels like a specific representation of the human experience as Straight comes in contact with all sorts of folks. Lost souls looking for direction, Good Samaritans, fellow war vets content chewing the fat, men handy with tractors or quick to offer shelter or some form of hospitality.

There’s something radical about these folks in their very simplicity, running counter to the way the culture has moved even 30 years on. What we appreciate about them is their candor; there’s a laconic spareness and a straightforward reality to these people and their dialogues.

Alvin’s not needy, but he’s always obliging for accommodation. Some people try and blow him off the road, horns blaring, but others see the nobility in his mission. He will not be dissuaded or moved because there is something or someone at the end of the road to make all of this worth it. There’s never a second thought of his going through with it.

Sure enough, he passes through the valley and over a hill to find a dilapidated farmhouse. He yells out to his brother, and out steps Lyle (Harry Dean Stanton). They sit down on the porch to share their presence with one another. Words would be nice, but they hardly feel necessary. In a generation so often distracted by so many things (especially cell phones), what a radical thing to be completely present with another human being. Again, it’s a dying art that Alvin Straight all but mastered.

If we were not primed already, it’s possible the ending might seem underwhelming, but then we spent this whole time with this man. It was about his journey, the people he meets along the way, and what he represents. There’s something in his sinew and his makeup worth taking note of.

Richard Farnsworth was an actor I was familiar with thanks to Anne of Green Gables on VHS. He was instantly likable in a series full of so much drama and theatrics; there was always something so genial and grounding about him. The Straight Story would wind up being his last film, and as he neared 80 years, he was stricken with cancer.

This film stands as a testament to what he was as an actor and human being. Plain, straightforward, but ultimately replete with all kinds of truth and goodness. I haven’t gotten trite of late, so allow me just this one digression. Disney doesn’t make movies like this anymore. But then again, how would they ever top a G-rated David Lynch film about a truly mythical tractor ride?

4/5 Stars

Note: This review was written before David Lynch’s passing on January 16, 2025

Whisper of The Heart is wholeheartedly a Japanese anime and yet learning John Denver’s “Country Roads” holds a relatively substantial place in the plotline might catch some off guard. After all, as the metropolitan imagery establishes our setting, we hear a version of the song playing against the bevy of passersby, cars, and convenience stores.

Whisper of The Heart is wholeheartedly a Japanese anime and yet learning John Denver’s “Country Roads” holds a relatively substantial place in the plotline might catch some off guard. After all, as the metropolitan imagery establishes our setting, we hear a version of the song playing against the bevy of passersby, cars, and convenience stores.