Richard Quine’s Strangers When We Meet proves to be a Technicolor feast on par with much of what Nicholas Ray, Douglas Sirk, and Vincente Minnelli were putting out at the same time. A lot of the immediate joy comes with getting a feel for life at the time.

Richard Quine’s Strangers When We Meet proves to be a Technicolor feast on par with much of what Nicholas Ray, Douglas Sirk, and Vincente Minnelli were putting out at the same time. A lot of the immediate joy comes with getting a feel for life at the time.

Certainly, it’s done up and made into a polished Hollywood middle class, but this serves the motives of the picture. In the meantime, we can busy ourselves taking in all the sights from the bus stops to the grocery stores, the cars, and all the mundane accents of life circa 1960. These would be all too easy to take for granted if not for the fact we are so far removed from that generation.

Kirk Douglas (who we just lost last week at age 103*) is an architect of some repute and though he doesn’t quite have 2.5 kids, he’s living the American Dream. He has a good job, a beautiful wife (Barbara Rush), and his latest project is being drawn up as we speak. Being a product of Douglas himself, Larry Coe is not about to have his vision compromised, and he’s imbued with a dogged bullheadedness evident in all facets of his life.

Kim Novak, in one respect, feels out of place as a suburban housewife and a mother. It’s not her obvious character type with that husky voice and golden allure of hers. And yet this dissonance serves her quite well as a woman who feels trapped and unfulfilled. The stoic aloofness she could always propagate says everything we need to know about her.

In her day, Kim Novak was seen as the answer to frisky and enticing Marilyn Monroe because while still alluring, she is also the antithesis. While neither is particularly far-ranging in their parts, their fundamental approaches are so very different.

Novak’s register is so low and, in a word, reserved. It’s nothing compared to Marilyn’s sing-song quality, but in a film like Strangers When We Meet one must wager it works far better. Even as she hardly feels like the domestic stereotype — as Marilyn does not — it somehow fits her prevailing qualities.

As Strangers When We Meet sets up its world and the relationships orbiting throughout the story, it becomes apparent the movie exhibits another facet of suburbia that complements Bigger Than Life, No Down Payment, or even Rebel Without a Cause. It’s this idea that even within these perceived oases of middle-class comfort, there is still a myriad of anxietieties and discontentments causing fractures at the seams.

Whereas Novak’s husband comes off as a loveless prude, Barbara Rush does her best to make the most of her marriage, romance, and all. She’s the one we feel the most sympathetic towards as it becomes all too obvious she might very well become collateral damage.

Because with two pretty faces as renowned as Kirk Douglas and Kim Novak — no matter who their spouses might be — we have a premonition that they will be getting together in some way, shape, or form. These are the unwritten rules of Hollywood moviegoing.

I wasn’t considering it at the time, but they first cross paths at the bus stop because their boys are friends. It’s Innocent enough. Then, it’s the aisle of the grocery store. Larry stirs up the courage (or the brashness) to invite Maggie to see his latest work project.

If we wanted to be purely critical of the man, we could say he is taken first and foremost by her extraordinary beauty. Though I feel like his wife is lovely in her own way. The movie suggests there is a bit more to their affair.

It begins because Maggie seems to understand him; she seems to encourage him in his work — to be genuinely impressed and interested in what he does. Maybe it strokes his ego, makes him feel more important, more heard than he’s felt in a long time. If it’s true of Larry, the same holds for Maggie as well. This coalescing of passion is what brings them together.

Walter Matthau is initially underused and yet with his telling look and a few words, he can insinuate even more into this story. I’m thinking in particular of the moment he tells his neighbor, “We’re like furniture in our own homes. Next door we’re heroes.” He senses the angst on the surface and no doubt suspects the fire burning between Larry and Maggie.

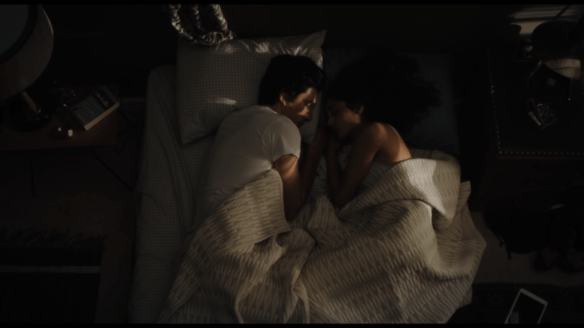

It comes to a head during a dinner party Larry’s wife puts on. There’s a sense this is her admirable attempt to win her husband back, in their social spheres with their friends, and then later, behind closed bedroom doors. Because she’s not blind; she can see her man drifting away from her, and she’s not going down without a fight.

These inferences remain out on the fringes suggesting the wants and desires of the men and women even as guests drone about crabgrass and how all women dress the same these days. You have to look beyond all the obfuscation to appreciate the sequences for what they are.

Take, for instance, the striking scene where Novak goes into the bedroom to pick up her coat only to see the intimate space, her face in the mirror — and wish it was hers — wish she could be sharing it with Larry. In the same sequence, she happens upon his inquisitive young son. When he asks her name she responds with “Maggie” — the name his father calls her — that’s somehow more intimate and more a measure of who she is as a human being.

Ed Mcbain’s script is not at all squeamish about melodrama. The apogee comes when the sleazy Matthau gives Larry a taste of his own medicine charging into his home while he’s away and making clear advances toward his wife. His actions seem to defy logic.

Is he merely doing this to stir up Coe or is it a genuine play for Eve’s affections? I’m led to believe it’s the latter because as it happens, it’s a devastating confrontation, even as it teeters on this unnerving precipice. We feel for Rush, victimized like she is really for the entire movie, but here it all stands right there in her living room. Even for an instant, she feels so completely vulnerable.

The rain pouring down outside acts as a sympathetic indicator if not only a torrent of renewed drama. The overstimulated soundtrack doesn’t do the performances any favors, but they leave a melting impression; we must ponder the outcomes.

Because affairs can rarely maintain the status quo. Their very definition makes them into this novel entity in one’s life breaking through the presumed drudgery of the everyday. But there comes a point — a slip-up or a guilty conscience — where they must be brought to light.

Douglas spends the majority of the movie constructing his latest cutting-edge home for a gabby author played by Ernie Kovacs. It’s apparent this yet-to-be-finished structure is a metaphor for his life — his hopes and aspirations outside of the conventional suburban life he leads.

He finishes it too, fully realized in all its glory, and still, we watch Kim Novak drive off on her own. This isn’t Picnic. There is not even a faint flicker of hope of a reunion some miles off in the distance. This feels like a permanent departure. Where the characters have chosen the so-called “noble thing,” to preserve their families in lieu of their own private and clandestine fantasies.

The completed space is a bit like Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House except it’s for a life (and a woman) he can never hope to have. It’s heartbreaking for any number of reasons. Not merely because they cannot be together. The layers go further. You wonder if their families can ever heal. How will this affect their children? What about their spouses? Is this just a temporary salve that will fail years down the road? We have no way of knowing. They are the ones who have to live with their choices.

3.5/5 Stars

*Note: I originally wrote this review soon after the passing of Kirk Douglas on February 5, 2020.