At first glance, this doesn’t seem like the type of picture suited for Steve McQueen and Natalie Wood. He was “The King of Cool.” She was a major player from childhood in numerous classics. Neither was what most people considered a serious actor. They were movie stars. They had charisma and general appeal to the viewing public.

At first glance, this doesn’t seem like the type of picture suited for Steve McQueen and Natalie Wood. He was “The King of Cool.” She was a major player from childhood in numerous classics. Neither was what most people considered a serious actor. They were movie stars. They had charisma and general appeal to the viewing public.

What we have here is a stark slice-of-life scenario. Even put in the context of her Italian family unit Wood feels slightly out of place. It’s the kind of portrayal that worked for Ernest Borgnine in Marty (1955) and other such pictures. The same if not more can be said of Steve McQueen with his parents. He’s hardly an Italian. But the chemistry is there and that’s almost more important.

Any criticisms or preconceptions aside there must be credit paid to our stars. All power to them for wanting to be in this picture and casting aside what might have been more glamorous material for something that might stretch their acting chops. Because in the mid-50s and onward we were beginning to see a more honest strain of drama in Hollywood films. I would hesitate to call this film complete realism but there’s a candid quality that’s unquestionable.

Love With The Proper Stranger manages to put a narrative to the kind of hushed up realities that needed to be brought to the light. It’s part daring, part matter-of-fact in its actual execution. Because in merely acknowledging its subject matter, even in a minor fashion, it starts a conversation that can lead to some sort of human understanding.

You see, the film opens in a bustling union hall where a freelance musician named Rocky (Steve McQueen) gets paged by someone. He comes face-to-face with a girl. He can’t remember her name but the face is familiar. There’s a smile of recognition. The reason she came to see him catches him off guard though. She wants to ask him to find her a doctor. Because you see, they had a one night stand (the title proves a poetic euphemism) and she’s pregnant. The rest you can put together for yourself. His reaction is not what she wanted.

And so that’s how they reconnect. At first, strained and then looking to gather enough funds to pay the doctor to get it done. They’re genial enough and understanding after the initial encounter. That’s part of what’s striking. Love With The Proper Stranger chooses to traverse a generally understated road in lieu of melodramatics.

Sure, she’s a sales clerk at Macy’s and her family is devoutly Catholic with her older brothers often nagging her to get married. And he’s broke and shacked up with a nightclub dancer (Edie Adams) who runs a doggy kennel in her apartment. Still, that’s all just white noise or at least only shading to what’s really of interest.

One of the most indicative moments occurs when they’re staked out in some god-forsaken rundown warehouse and they open up about romance as they wait for their appointment. Their assertions are meant to make us understand them better but what we are provided is a level-headed dialogue that wears cynicism openly while honestly trying to figure out if love, kisses, and marriage, all those things that the movies and music seem to romanticize are even worth it after all.

During the very same conversation, Wood’s character confesses, “All I felt was scared and disgusted with myself.” Nothing more. Waiting for the bells and the banjos to sound doesn’t work. And when they go to the shady meetup and get funneled to a backroom it’s not any prettier. In fact, it’s probably worse. And it’s these moments that grieve me and pain my spirit. That anyone would have to deal with such an unfeeling environment. It’s not about condoning their behavior or not but being truthful to the way things actually are.

Meanwhile, the film’s latter half is decidedly lighter as if our main characters have settled into the new reality at hand. I suppose that’s the way real life is. It keeps on moving no matter the circumstances. Whatever decisions you have chosen and whomever you pick to live your life with.

Angie rebuffs his gallant proposal of marriage, finds her own apartment, and doesn’t complain about the road ahead. She didn’t need him to fall on his sword or take his medicine. Whatever apt metaphor you choose. That’s not her idea of a sound union. Instead, she tries to content herself with a well-meaning cook named Anthony (Tom Bosley) while Rocky piddles around discontentedly. The directness of the story allows us to dig in; it’s the comic tones of the unwinding romance that guide us to the end. Our leads see it through splendidly with a charming grace that’s collected and still sincere.

Although he will never earn much repute because his offerings are generally low-key, I will continue to do my best in cultivating an appreciation for Robert Mulligan as a director, as well as Alan Pakula. Not that they were quite as socially conscious as a Stanley Kramer or as intent on pushing boundaries like an Otto Preminger but To Kill Mockingbird (1962) and this picture are both statements of quality in themselves.

In fact, it’s rather bewildering that despite the names above the title, an immersive setting in New York’s Little Italy, and a genuine storyline, Love With The Proper Stranger is easily glossed over. Maybe it goes back to our stars. It’s not as monumental as The Great Escape (1963) or The Great Race (1965). And it’s not lauded to the degree of West Side Story (1961) or Bullitt (1966). That’s okay. It has no bearing on whether you enjoy it or not.

Not to undercut everything that I’ve already said but I’ve waited long enough. The final question I was left with is whether or not Natalie Wood was still friends with Santa Claus working at Macy’s. But then again, maybe in the world she finds herself in, Santa can’t fix all her problems. I suppose that’s okay too.

4/5 Stars

It’s easy to assume that Picnic is a film that time had not been very kind to. If you do a cursory glance at contemporary reviews, the majority appear far from glowing and my own reason for returning to this romance was based on a mild interest in a cultural artifact rather than an actual investment in the film itself.

It’s easy to assume that Picnic is a film that time had not been very kind to. If you do a cursory glance at contemporary reviews, the majority appear far from glowing and my own reason for returning to this romance was based on a mild interest in a cultural artifact rather than an actual investment in the film itself.

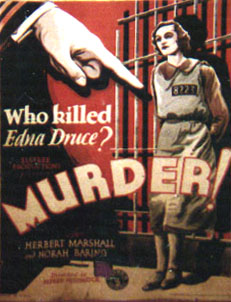

Although Hitchcock did many riffs off the same themes, he very rarely tried to do the same film twice over. The Man Who Knew Too Much might be the one exception and even then if you place these two thrillers from 1934 and 1956 up next to each other, they’re similarities are fairly nominal.

Although Hitchcock did many riffs off the same themes, he very rarely tried to do the same film twice over. The Man Who Knew Too Much might be the one exception and even then if you place these two thrillers from 1934 and 1956 up next to each other, they’re similarities are fairly nominal. Alfred Hitchcock captures the pure bedlam that overtakes a neighborhood when their peaceful dreams are rudely disrupted by an awful din. As is customary everyone is in a foul mood, peers out their windows, bickers with everyone else, and moves into action.

Alfred Hitchcock captures the pure bedlam that overtakes a neighborhood when their peaceful dreams are rudely disrupted by an awful din. As is customary everyone is in a foul mood, peers out their windows, bickers with everyone else, and moves into action. For some Black Panther might be a stellar actioner, consequently, brought to us by a visionary director, Ryan Coogler. It’s top-tier as far as Marvel movies come; there’s little doubt. For others, I completely understand if Black Panther rocks their entire paradigm because there’s so much of note here. The box office seems to confirm that just as much as the dialogue that has been created in its wake.

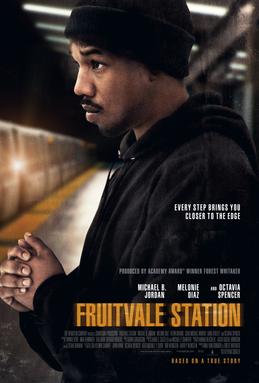

For some Black Panther might be a stellar actioner, consequently, brought to us by a visionary director, Ryan Coogler. It’s top-tier as far as Marvel movies come; there’s little doubt. For others, I completely understand if Black Panther rocks their entire paradigm because there’s so much of note here. The box office seems to confirm that just as much as the dialogue that has been created in its wake. Ryan Coogler is from Oakland, California. He was attending USC Film School in 2009 when Oscar Grant III was shot near the BART station. From those experiences were born his first project. He envisioned Michael B. Jordan in the lead role. Thankfully his vision and the casting came to fruition.

Ryan Coogler is from Oakland, California. He was attending USC Film School in 2009 when Oscar Grant III was shot near the BART station. From those experiences were born his first project. He envisioned Michael B. Jordan in the lead role. Thankfully his vision and the casting came to fruition. “You can fool all of the people some of the time, you can even fool some of the people all the time, but you can’t fool all the people all the time.” ~ Inscription in the Fortune Cookie

“You can fool all of the people some of the time, you can even fool some of the people all the time, but you can’t fool all the people all the time.” ~ Inscription in the Fortune Cookie In one sense Blackmail proves to be a landmark in simple film history terms but it’s also a surprisingly frank picture that Hitchcock injects with his flourishing technical skills. It’s of the utmost importance to cinema itself because it literally stands at the crossroads of silent and talking pictures and holds the distinction of being one of Britain’s first talkies.

In one sense Blackmail proves to be a landmark in simple film history terms but it’s also a surprisingly frank picture that Hitchcock injects with his flourishing technical skills. It’s of the utmost importance to cinema itself because it literally stands at the crossroads of silent and talking pictures and holds the distinction of being one of Britain’s first talkies.