Before the exoticism of Casablanca, Algiers, or even Road to Morroco, there was Josef Von Sternberg’s just plain Morocco but it’s hardly a run-of-the-mill romance. Far from it.

Before the exoticism of Casablanca, Algiers, or even Road to Morroco, there was Josef Von Sternberg’s just plain Morocco but it’s hardly a run-of-the-mill romance. Far from it.

Although it involves soldiers, it’s also hardly a war film but instead set against a backdrop that presents an exotic love affair as only Sternberg could. With a sultry Marlene Dietrich matched with a particularly cheeky Gary Cooper, it instantly looks to be an interesting dynamic because they couldn’t be more different.

She, a radiant German beauty with an evocative pair of eyes to go with a somewhat sullen demeanor. He, America’s ruggedly handsome ideal of what a man should be. And it in Sternberg’s film neither of them is what we’re used to.

He’s a renegade soldier in the French Foreign Legion. She’s a cabaret singer (that hasn’t changed) but she also manages to be French, not German. Somehow it’s easy enough to disregard because it’s not necessary to get caught up on the particulars.

All that matters is that they both find themselves in Morocco. He is traipsing through town with his division and spends some free time taking in her floor show along with the rest of the rowdy masses. Neither one of them has found someone good enough for them — they’re equal of sorts. He’s a gentleman cad if you will and she’s hardly an upstanding woman, making a living in a dance hall but there’s more to her. It’s hinted that she once had love, perhaps.

It takes so long for them to actually speak to each other but they’re flirting from the first moment they lay eyes on each other. They say so much through simple expressions all throughout the cabaret show. Things proceed like so. She slips him a flower, then an apple, and finally a key. At this point, he gets the drift and we do too.

Later that evening he winds up at her flat and they spend their most substantial time together. It’s full of odd exchanges, meandering conversations that run the risk of sounding aloof. In fact, their entire relationship is replete with oddities.

Another man (Adolph Menjou) is smitten with Amy but he’s never driven to jealousy. He’s good-natured and generous in all circumstances. People like him must only drift through the high societies.

She holds onto some wistful longing for the tall dashing Legionnaire who drifted through her life. But she’s slow to act. Meanwhile, he hardly seems to take it as a blow to his love life when she resigns to stay behind. After all, he’s quite the ladies’ man. He probably doesn’t need another woman. He’s always got several draped over each arm.

Morocco is a film interesting for the spaces that it creates and not necessarily for the story it develops. Visually, by the hands of the director and then simultaneously by Cooper and Dietrich as they work through their scenes both together and apart. Though it might in some ways lack emotional heft, its stars are still two invariably compelling romantic stars of the cinema.

Somehow it still manages to be quite lithe and risque when put up next to its contemporaries. It exudes a certain mischievousness of the Pre-Code Era. It’s not so much licentiousness and debauchery but it wishes to suggest as much. It can be implied without actually going through all the trouble of showing it.

Dietrich sums it up perfectly in her little diddy about Eve (What am I bid for my apple/ the truth that made Adam so wise? On the historic night/ when he took a bite/ they discovered a new paradise). In essence, the world got a lot more exciting when sex and deceit were brought into the equation. Maybe she misses the implications the Fall of Man but that’s precisely the point. Still more Pre-Code sauciness case and point.

In the final moments, where Dietrich abandons her heels and goes slinking across the sand chasing after her man, it feels less like a romantic crescendo or even a tragic turn and more like a ploy by the director to make his leading lady the focal point of his story one last time. She is granted the final bit of limelight. Because in many ways Gary Cooper could not win when it came to upstaging Marlene Dietrich orchestrated by her devoted partner/director Sternberg. Thus, Morocco turns out to be a rather curious love story different than some of the more typical Hollywood fare.

4/5 Stars

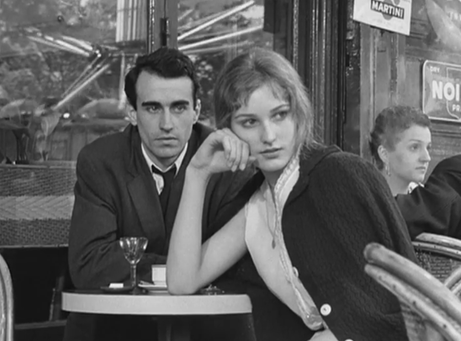

Pickpocket is an intricately staged, truly intimate character study from the inimitable Robert Bresson solidifying itself as one of his greatest works. As was his practice, Bresson took Martin LaSalle, a non-actor to be his leading protagonist.

Pickpocket is an intricately staged, truly intimate character study from the inimitable Robert Bresson solidifying itself as one of his greatest works. As was his practice, Bresson took Martin LaSalle, a non-actor to be his leading protagonist. The opening credits of Vivre sa Vie commence with the opening note “dedicated to B-movies” and indeed many of Jean-Luc Godard’s best films could make the same claim. They’re smalltime stories about little people living rather pathetic lives if you wish to be brutally honest. This isn’t Hollywood.

The opening credits of Vivre sa Vie commence with the opening note “dedicated to B-movies” and indeed many of Jean-Luc Godard’s best films could make the same claim. They’re smalltime stories about little people living rather pathetic lives if you wish to be brutally honest. This isn’t Hollywood. It’s a joy to watch Agnes Varda dance. Or, more precisely, it’s a joy to watch her camera dance. Because that’s exactly what it does. Her film opens in color, catching our attention, vibrant and alive as the credits roll and a young woman (Corinne Marchand) gets her fortune read by an old lady. She’s worried about her fate. We can gather that much and this is her way of coping. Superstition and tarot cards but she’s trying and the results are not quite to her fancy.

It’s a joy to watch Agnes Varda dance. Or, more precisely, it’s a joy to watch her camera dance. Because that’s exactly what it does. Her film opens in color, catching our attention, vibrant and alive as the credits roll and a young woman (Corinne Marchand) gets her fortune read by an old lady. She’s worried about her fate. We can gather that much and this is her way of coping. Superstition and tarot cards but she’s trying and the results are not quite to her fancy. Whaddya hear, whaddya say ~ Jimmy Cagney as Rocky Sullivan

Whaddya hear, whaddya say ~ Jimmy Cagney as Rocky Sullivan John Garfield was never the most dashing of leading men but nevertheless, he was always thoroughly compelling as ambitious working class stiffs during the 1940s. He had a straightforward tenacity about him like he had to fight his way to the top. At the same time likable and destined for trouble right out of the gates. You can cheer for him and still rue the decisions that he makes. That’s what makes his foray as boxing champ Charlie Davis all the more believable. His aspirations are of a very real nature and they give his character a genuine makeup.

John Garfield was never the most dashing of leading men but nevertheless, he was always thoroughly compelling as ambitious working class stiffs during the 1940s. He had a straightforward tenacity about him like he had to fight his way to the top. At the same time likable and destined for trouble right out of the gates. You can cheer for him and still rue the decisions that he makes. That’s what makes his foray as boxing champ Charlie Davis all the more believable. His aspirations are of a very real nature and they give his character a genuine makeup. Father hear my prayer. Forgive him as you have forgiven all your children who have sinned. Don’t turn your face from him. Bring him, at last, to rest in your peace which he could never have found here. ~ Ida Lupino as Mary Malden

Father hear my prayer. Forgive him as you have forgiven all your children who have sinned. Don’t turn your face from him. Bring him, at last, to rest in your peace which he could never have found here. ~ Ida Lupino as Mary Malden Films Noir often find their hooks in lurid titles but also in metaphor. Ride the Pink Horse fits into the latter category as pulled from the pages of Dorothy B Hughes and adapted by Ben Hecht & Charles Lederer. The horse can be taken in the literal sense as one of the wooden animals that go round and round on the local carousel but there’s some symbolism in this opulent creature. In some distant way, it’s the fantasy of a different life that every man seems to crave when he doesn’t have it. But still, he strives and grinds to get closer and closer to it. More often than not he does not succeed in finding so-called contentment.

Films Noir often find their hooks in lurid titles but also in metaphor. Ride the Pink Horse fits into the latter category as pulled from the pages of Dorothy B Hughes and adapted by Ben Hecht & Charles Lederer. The horse can be taken in the literal sense as one of the wooden animals that go round and round on the local carousel but there’s some symbolism in this opulent creature. In some distant way, it’s the fantasy of a different life that every man seems to crave when he doesn’t have it. But still, he strives and grinds to get closer and closer to it. More often than not he does not succeed in finding so-called contentment. And it’s from these opening moments that we try to get a line on Gagin by watching his every move and word. He’s brusque and abrasive with almost crazed features — constantly suspicious, demanding, and sour. He had a little too much cyanide for breakfast (although he does like fruit cocktail). Just as we watch him with interest, his probing eyes case every joint and every person he comes in contact with. Because, if it’s not obvious already, he’s not come to San Pablo for R & R. He’s come to town to avenge his dead army buddy, who was double-crossed and put out of a commission by a very big man (Fred Clark).

And it’s from these opening moments that we try to get a line on Gagin by watching his every move and word. He’s brusque and abrasive with almost crazed features — constantly suspicious, demanding, and sour. He had a little too much cyanide for breakfast (although he does like fruit cocktail). Just as we watch him with interest, his probing eyes case every joint and every person he comes in contact with. Because, if it’s not obvious already, he’s not come to San Pablo for R & R. He’s come to town to avenge his dead army buddy, who was double-crossed and put out of a commission by a very big man (Fred Clark). Just as there is a cultured femme fatale (Andrea King), her counterpoint is the tentative Pila (played sympathetically but rather unfortunately by Wanda Hendrix), who floats in to watch over Gagin even when he doesn’t want her around. She stays anyways.

Just as there is a cultured femme fatale (Andrea King), her counterpoint is the tentative Pila (played sympathetically but rather unfortunately by Wanda Hendrix), who floats in to watch over Gagin even when he doesn’t want her around. She stays anyways. There’s a very special place in my heart for Rocky (1976) and I choose those words very carefully. The reason being, subsequent films lost the appeal of the original and I simultaneously lost interest in the franchise. Perhaps it’s because, after Sylvester Stallone’s breakthrough film, the series lost much of its unassuming charm. It was no longer an underdog story. It no longer felt as personal and intimate.

There’s a very special place in my heart for Rocky (1976) and I choose those words very carefully. The reason being, subsequent films lost the appeal of the original and I simultaneously lost interest in the franchise. Perhaps it’s because, after Sylvester Stallone’s breakthrough film, the series lost much of its unassuming charm. It was no longer an underdog story. It no longer felt as personal and intimate. Sophie Scholl: The Final Days is a film that people need to see or at the very least people need to know the story being told. For those who don’t know, Sophie Scholl was a twenty-something college student. That’s not altogether extraordinary. But her circumstances and what she did in the midst of them were remarkable.

Sophie Scholl: The Final Days is a film that people need to see or at the very least people need to know the story being told. For those who don’t know, Sophie Scholl was a twenty-something college student. That’s not altogether extraordinary. But her circumstances and what she did in the midst of them were remarkable.