The Horse Soldiers is the one and only teaming of John Wayne and William Holden in a story based on the raids of Colonel Benjamin Grierson during the Civil War. John Ford casts the story as a brand of folklore carried through the air by the songs sung on the trail by a regiment riding in their formation. “I Left My Love” and “When Johnny Comes Marching Home” are the two prime examples ringing out on more than one occasion.

Wayne is the journeyman military man who is intent on carrying out his mission. But his exacting, army first mentality soon sets him at odds with a newly assigned regimental surgeon from up north, Major Henry Kendall (William Holden), who is appalled by the conditions of the war. His vow to do his very utmost to save life ultimately butts up against the other man’s own sense of duty. It seems that they will never be reconciled.

Though Wayne rarely carries a firearm on camera, he does readily smack some people around. And yet these very discrepancies are an indication of why the man is so hard to figure. There’s a decency to him revealing itself in isolated moments even as he leads his men on a mission to decimate the enemy’s contraband by the most decisive means possible.

When William Tecumseh Sherman, whose name is thrown around at least a few times, famously asserted “war is hell” it was not a quip. I believe he meant it wholeheartedly, coming from a man who was willing to do what was required to win. Not out of malice but, on the contrary, out of a sense of duty. But that unswerving call to duty led him to undertake some pretty ruthless means — horribly cruel in their execution. A like-minded figure can be found in Colonel Marlowe.

He brazenly leads his men into the heart of Reb Country and they are eventually met by an onslaught of Confederates, as they snake their way far behind enemy lines. The irony is the fact that in civilian life the Colonel was a railroad engineer and now he must watch his men bend the southern railroad lines into “Sherman Neckties” to impede future transportation.

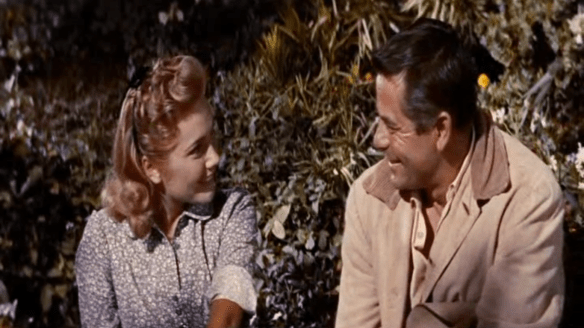

If Major Kendall is the initial manifestation of the opposition Marlowe faces, the next front comes courtesy of a southern belle named Miss Hannah Hunter (Constance Towers). Her tactics include a sly show of hospitality in an effort to pass secrets to her countrymen. As a result, the Colonel has no recourse but to bring her along on their raid, doing his best to treat her nobly, within reason; though she continues to despise his guts.

There’s a recurring theme as you can see with both Holden and Towers’ characters trying to decide what to make of this man. Although her part is hardly groundbreaking, a shoutout must be given to tennis extraordinaire and barrier breaker Althea Gibson for playing Miss Hunter’s loyal maid Lukie.

Political views in real life played into the heated character dynamics between our two stars, with Wayne’s overt conservative values completely at odds with Holden’s liberal leanings. While it might have helped the picture — to some degree — it meant the two vowed to never again appear together. Take it for what it’s worth.

Otherwise, The Horse Soldiers is as enjoyable as a Civil War film can be. Rather unbelievably, this is the only feature-length Civil War film that Ford would ever do. Pictorially it’s about as arresting as most anything he conceived during the period. However, this one doesn’t feel like a commentary or really like it’s trying to make any kind of statement. It’s also easy to call into question some of the character mechanics as detailed by the script.

There are some people who live and others who die. Good deeds are committed and likewise, evil. People hate each other and some fall in love. Sometimes in the same instance. Such is the blurred landscape of a “civil war” — a term that forever has been questioned due to its very oxymoronic nature.

John Ford himself was even more cantankerous than usual because his doctor had forbidden him from drinking and the loss of a stuntman in the climactic battle scenes only soured matters. It’s a fair assumption the picture may have suffered as a result with the director tiring of the project in the end, all but cutting production short. Regardless, it’s a generally agreeable adventure plucked out of history and touched up for the viewing public in exhilarating fashion. There needn’t be more to it.

3.5/5 Stars

The picture showcases a parched landscape of cacti and dusty trails — the arid terrain accentuated by purposely tinted photography. It’s aided by that bleak black & white palette courtesy of Charles Lawton Jr., just as Delmer Dave’s earlier western, Jubal (1956), was made by its vibrant imagery around Jackson Hole. Each fits the mood called for impeccably.

The picture showcases a parched landscape of cacti and dusty trails — the arid terrain accentuated by purposely tinted photography. It’s aided by that bleak black & white palette courtesy of Charles Lawton Jr., just as Delmer Dave’s earlier western, Jubal (1956), was made by its vibrant imagery around Jackson Hole. Each fits the mood called for impeccably.