Right away, in the very first moments, we know something’s amiss when the driver of a passing wagon notes to the woman at his side that they just passed her father…and they proceed to keep going without even a word of greeting.

It’s true that Ramrod is a riff on the age-old family feud but it involves several other men who are tied up in it too. Frank Ivey (Preston Foster) plays god where nothing and no one sees the light of day without his say so. Because remember these are the days when whoever had the most firepower and the ability to lean on others was king.

True, the sheriff (Donald Crisp) has a duty to uphold the peace but his jurisdiction and authority can only reach so far. One man against an entire posse doesn’t amount to much. Important to this story is that the old man from the opening scene, Ben Dickason (Charles Ruggles), has long sided in all of his affairs with Ivey. He’s even told his daughter to marry him and he does it again when the bully runs her latest beau out of town.

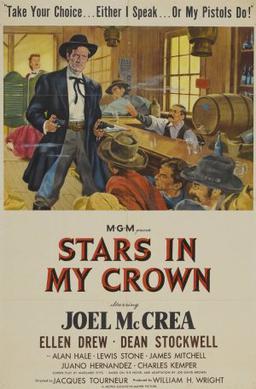

But Connie Dickason (Veronica Lake) is resolute and not about to let anyone push her around and so she decides to take the land bequeathed to her and try and make a go of it as a cattle rancher. She knows its an uphill battle in opposition to Ivey but one key to the enterprise is Dave Nash (Joel McCrea) who finds himself all of the sudden on the wrong side of Ivey as well. Now he has a reason to take up an offer from Connie becoming the ramrod of her outfit.

Soon he assembles a workforce including his pal Bill Schell (Don DeFore) to see the game through by legal means playing by the rules because the local sheriff is a buddy and Dave is not about to put his friend in a compromising position. He respects him too much. Others are not so valiant. For all intent and purposes, total war has begun.

First Connie’s homestead is razed to the ground, a cowhand is given a going over, and another man is gunned down in retaliation. Both sides have blood on their hands’ thanks to this eye for an eye mentality that continues to escalate matters. A herd of cattle is stampeded. The sheriff gets it for attempting to enact justice. Dominoes continue to tumble with each subsequent shotgun blast of malice.

Dave winds up as a fugitive for avenging his friend’s death by gunning down his purported killer. He finds himself wounded and trying to sneak past the searching eyes of Ivey. They manage to get him away to a secluded cave but even their his safety is put in jeopardy by — you guessed it — Connie Dickason. She has her meddling hands in many things.

The one person who won’t let him down, despite a myriad of faults, is Bill and he devises a plan to draw the enemy away from his friend by acting as a decoy. The posse winds into the mountain crags to gun Dave down for good; they fail to comprehend who they are actually dealing with.

With her then-husband directing, it makes sense that the film provided a prominent berth for Lake. It’s a juicy role full of a mixture of innocent intentions and conniving. There’s absolutely no question about it; it’s another femme fatale role as she plays a “man’s game” by pitting all the men in her life against each other to get her way so she can pick up the pieces. In totality, it’s a nifty bit of maneuvering to get the desired results, successfully pouting her way to the top. But a curious counterpoint is Rose (Arlene Whelan) who is without question the guardian angel of the picture tugging at Daves heartstrings while Connie continually entangles him.

Retroactively it’s seamlessly easy to label this a noir-western sharing company with such hybrids as Pursued (1947) and Yellow Sky (1948). This breed of western is dark and brooding, concerned with psychological warfare as much as it is rough and tumble enforcement of justice. We half expect Ramrod to cram itself down our throats and it might as well with all that goes down.

The cast is steady with a plethora of recognizable character actors including Charles Ruggles and the diplomatic hand of Donald Crisp. Don DeFore as the bright-eyed ranch hand nevertheless knows how to hold a grudge with the best of them. You’ve never seen him so grungy. Lloyd Bridges fills a near bit part as a hot-headed heavy as usual while the scapegoat Virg is portrayed by Wally Cassell (Cassell lived to the ripe, old age of 103). With the reteaming of Lake and McCrea we had a reunion of Sullivan’s Travels (1941) and yet the reason it didn’t happen earlier was McCrea was not all that fond of his leading lady. By no means does that detract from this minor western success.

3.5/5 Stars

Though the image quality of the print I saw hardly stands the test of time, there’s something almost modern about The Virginian’s characterizations or at least what it deems interesting to show.

Though the image quality of the print I saw hardly stands the test of time, there’s something almost modern about The Virginian’s characterizations or at least what it deems interesting to show.