I never thought I’d get so fed up with hearing the name “Fefe.” But it’s true. There’s a first time for everything. In fact, Fefe is the name of our main character played so magnificently by Italian icon Marcello Mastroianni. In my very narrow view, he still very much epitomizes Italian cinema for me.

I never thought I’d get so fed up with hearing the name “Fefe.” But it’s true. There’s a first time for everything. In fact, Fefe is the name of our main character played so magnificently by Italian icon Marcello Mastroianni. In my very narrow view, he still very much epitomizes Italian cinema for me.

As for the film, a Sicilian Baron Ferdinando finds himself in rather an unfortunate conundrum — at least from his point of view. He relates through voice-over his family dynamic, with his parents, his soon to be engaged sister, his doting wife (Daniela Rocca), and of course his beautiful ingenue cousin Angela (Stefania Sandrelli). Aside from not being particularly enthralled with married life, the bigger problem is that Ferdinando is infatuated with Angela. He can’t take his eyes off her.

For those who are paying attention this comedy from director Pietro Germi, at times feels strikingly similar to the screwball comedies of Classic Hollywood where men such as Preston Sturges made light work of society by skirting censorship and building a barrage of gags almost to the point of being incomprehensible. But they might also conjure up comparisons with the darkly funny Ealing comedies out of England. And it’s true that films like Divorce Italian Style also carry a very particular name, “Commedia all’italiana” or comedy in the Italian way.

What becomes evident in a film such as Divorce Italian Style is the pointed attack on Italian social mores — the very framework that the culture is built on — and all involved are poking fun. Morality, class distinction, even the institution of marriage, are all dissected satirically as our protagonist goes through his life dreaming of knocking his wife off and living happily ever after with Angela — a girl that shares his affection — if only society didn’t say otherwise (she gets whisked to a life in a convent to maintain her purity). Not to be deterred, the Baron attempts to hitch his wife up with a suitable suitor and as the shameful scandal finally breaks over his wife, he secretly jumps for joy. He’s getting a step closer to what he wants.

Meanwhile, the men about town all ogle at every girl that happens to walk by. Fefe’s old man is constantly harassing the maid, and more than once he walks in on his sister and her beau making out passionately. There’s even a theatrical screening of Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (also starring Mastroianni) which literally seems to break any form of censorship in the town. The crowds flock to it joyously — men and women alike — because they want to see the lavish romance projected up onto the screen.

Mastroianni is not surprisingly a long way off from his debonair lovers taken the likes of La Dolce Vita, La Notte or 8 and 1/2. He goes through the film with a certain comedic despondency. He’s hardly a real figure. Comic and dismal with overblown ideas of how to make his existence invariably better. It’s quite a display because while it’s easy to laugh it’s also rather pitiful.

So Divorce Italian Style is perhaps even more audacious than the screwball comedies of the 30s and 40s. Because it gives the plotting Fefe the “happy” ending he was hoping for. It actually gives it to him, but the comic (or sad) thing, in the end, is that his girl is already playing footsies with another man. You see if we look at what is going on here, he’s never going to find contentment. The ultimate irony, if there was a sequel, is that it would probably show Fefe actually trying to kill his wife because she’s cheating on him. Then it wouldn’t be so funny.

Yes, the strict societal pressures put on the members of this Sicilian community undoubtedly deserve to be questioned. There is so much obvious hypocrisy bubbling up through the layers of society and it makes for provocative comedy. But also there’s something to be said for living life under some sort of moral framework. Otherwise, life is purely about our pleasures, what makes us feel good, what our desires are and oftentimes those fail to regard what is beneficial for others. Needless to say, I’m partial to “Marriage,” not “Divorce” Italian Style — or any other way for that matter. However, I won’t even try to tackle the whole marrying your cousin thing. This is a comedy after all and Stefania Sandrelli is quite pretty. I don’t blame “Fefe” too much. He’s only human.

4/5 Stars

“He will be your true Christian: ready to turn the other cheek, ready to be crucified rather than crucify” ~ Minister of The Interior

“He will be your true Christian: ready to turn the other cheek, ready to be crucified rather than crucify” ~ Minister of The Interior

Despite being dated and marred by the imprint of imperialism, this initial entry of the well-remembered Tarzan serial of the 1930s and 4os, based on the works of Edgar Rice Boroughs, is a surprisingly gripping pre-code tale of perilous adventure.

Despite being dated and marred by the imprint of imperialism, this initial entry of the well-remembered Tarzan serial of the 1930s and 4os, based on the works of Edgar Rice Boroughs, is a surprisingly gripping pre-code tale of perilous adventure. Furthermore, Johnny Weissmuller is not even the first Tarzan (purportedly the sixth incarnation) but he outshines all his predecessors who have been lost to history. It helped that he remains one of the most iconic Olympians and American swimmers of the 20th century, winning 5 Gold Medals. And he shows his prowess not only swinging from the treetops but in his true element, gliding through the water.

Furthermore, Johnny Weissmuller is not even the first Tarzan (purportedly the sixth incarnation) but he outshines all his predecessors who have been lost to history. It helped that he remains one of the most iconic Olympians and American swimmers of the 20th century, winning 5 Gold Medals. And he shows his prowess not only swinging from the treetops but in his true element, gliding through the water. “There live not three good men unhanged in England. And one of them is fat and grows old.”

“There live not three good men unhanged in England. And one of them is fat and grows old.” The triangle with Prince Hal (Keith Baxter) vying for the affection of his father King Henry IV (John Gielgud), while simultaneously holding onto his relationship with Falstaff is an integral element of what this film is digging around at. But there’s so much more there for eager eyes.

The triangle with Prince Hal (Keith Baxter) vying for the affection of his father King Henry IV (John Gielgud), while simultaneously holding onto his relationship with Falstaff is an integral element of what this film is digging around at. But there’s so much more there for eager eyes. And it’s only one high point. Aside from Welles’s towering performance, Jeanne Moreau stands out in her integral role as Doll Tearsheet, the aged knight’s bipolar lover who clings to him faithfully. The cast is rounded out by other notable individuals like John Gielgud, Margaret Rutherford, and Fernando Rey.

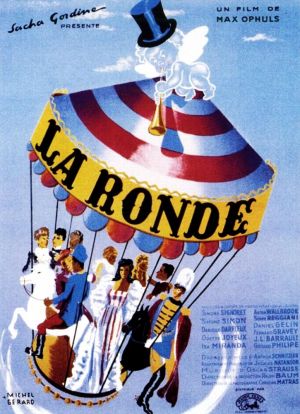

And it’s only one high point. Aside from Welles’s towering performance, Jeanne Moreau stands out in her integral role as Doll Tearsheet, the aged knight’s bipolar lover who clings to him faithfully. The cast is rounded out by other notable individuals like John Gielgud, Margaret Rutherford, and Fernando Rey. If you know anything about director Max Ophuls you might realize his preoccupation with the cycling of time and storyline, even in visual terms. He initiates La Ronde with a lengthy opening shot that, of course, involves stairs (one of his trademarks), and the introduction of our narrative by a man who sees the world “in the round.” He brings our story to its proceedings, introducing us to the Vienna of 1900. It’s the age of the waltz and love is in the air — making its rounds. It’s meta in nature and a bit pretentious but do we mind this jaunt? Hardly.

If you know anything about director Max Ophuls you might realize his preoccupation with the cycling of time and storyline, even in visual terms. He initiates La Ronde with a lengthy opening shot that, of course, involves stairs (one of his trademarks), and the introduction of our narrative by a man who sees the world “in the round.” He brings our story to its proceedings, introducing us to the Vienna of 1900. It’s the age of the waltz and love is in the air — making its rounds. It’s meta in nature and a bit pretentious but do we mind this jaunt? Hardly. The original title in Italian is Ladri di biclette and I’ve seen it translated different ways namely Bicycle Thieves or The Bicycle Thief. Personally, the latter seems more powerful because it develops the ambiguity of the film right in the title. It’s only until later when all the implications truly sink in.

The original title in Italian is Ladri di biclette and I’ve seen it translated different ways namely Bicycle Thieves or The Bicycle Thief. Personally, the latter seems more powerful because it develops the ambiguity of the film right in the title. It’s only until later when all the implications truly sink in.