Watching films with French treasure Mr. Hulot (Jacques Tati) is a wonderful experience because, in some respects, it feels like he brings out the child in me. And if history is any indication — I’m not the only one — others feel this sensation too.

Watching films with French treasure Mr. Hulot (Jacques Tati) is a wonderful experience because, in some respects, it feels like he brings out the child in me. And if history is any indication — I’m not the only one — others feel this sensation too.

It’s not sophisticated humor. The laughs are not dependent on any amount wit or mature understanding, but it’s universal. Everyone, whatever age, language or temperament, can laugh along with Monsieur Hulot.

Once more it’s easy to see his debt to the great silent stars and his use of sound is always impeccable yet still outrageous in the same breath. It accentuates anything on the screen with auditory hyperbole that is absolutely brilliant. Any sound imaginable is amplified in Tati’s memorable everyday comedic symphony of noise.

If you wanted a plot Trafic, as expected, has very little. Mr. Hulot, for a reason not explained to us, is now working for an automobile company named Altra that is preparing for a big car show in Amsterdam. He along with a truck driver named Marcel and Ms. “Public Relations” (American model Maria Kimberly) must weather the roads and every hiccup imaginable to make it to the show on time. She streaking in her bright yellow convertible and they riding in their truck cursed with flat tires and an empty gas tank among other ailments. It’s hardly a spoiler to say that they don’t quite make it there on schedule.

Jacques Tati was always one to playfully nudge at our modern culture obsessed with technology, expedience and, of course, automobiles. However, there’s nothing terribly vindictive about the way he goes about it. In contrast to the images of hustle and bustle and “progress,” there are also a great many that take comfort in the tranquility of farm life or quaint cottages. Everyday people and their mundane lives that, while idiosyncratic, are in no way inconsequential. He is a director who makes us appreciate people more. Mechanics, old couples, even cats, and dogs.

Many viewers undoubtedly will remember the crazy traffic jam with cars careening everywhere, hubcaps and tires rolling every which way and so on. It’s comedic madness. In fact, for numerous reasons, it’s easy to juxtapose Trafic with an earlier French film of a very different sort, Jean-Luc Godard’s political satire Weekend, which has some massive traffic of its own. And Tati creates comparable chaos, mischief and so on but I prefer his method of execution. Because he finds the charm and humor in every situation — even a car accident (with the multitudes simultaneously relieving the cricks in their joints). There’s no spite, cynicism or anything of that sort. He doesn’t feign pretentiousness, choosing instead to remain comically genuine right to the end.

That’s why there’s something so endearing and satisfying about Mr. Hulot. He remains unchanged and unmarred by the world around him. We can count on him to be the same as he ever was — the same hat, the same coat, the same pipe and the same hesitant gate. Maybe his adventures are not the most titillating. Some people admittedly will not like Trafic. It’s either too meandering like Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday or too jumbled compared to the exquisite patchwork ballet that makes up Tati’s earlier masterwork Playtime.

But, no matter, Tati is still a joy for what he brings to the screen, for those who are acquainted with his work and those who are willing to join an ambling adventure full of small nuggets of humor. Here is a film that through inconspicuous nose picking, windshield wipers, and road rage tells us more about humanity than many other more ostentatious films are able to manage. Trafic is certainly worthwhile.

4/5 Stars

“You can’t just do anything at all and then say ‘forgive me!’ You haven’t changed a bit.” ~ Colette

“You can’t just do anything at all and then say ‘forgive me!’ You haven’t changed a bit.” ~ Colette Antoine Doinel is a character who thinks only in the cinematic and it is true that he often functions in a bit of a faux-reality. He seems normal but never quite is. He seems charismatic but we are never won over by him completely. Still, we watch the unfoldings of his story rather attentively.

Antoine Doinel is a character who thinks only in the cinematic and it is true that he often functions in a bit of a faux-reality. He seems normal but never quite is. He seems charismatic but we are never won over by him completely. Still, we watch the unfoldings of his story rather attentively. Why do you watch me? -Magda

Why do you watch me? -Magda And despite the clandestine nature of his activities he still somehow remains innocent in the eyes of the beholder. Daily he works at the post office behind the glass and in the evening he studies languages. But he’s continually drawn to this lady across the way. He feels like he knows her. He wants any pretense to meet her and so he creates a bit of fate anytime he can.

And despite the clandestine nature of his activities he still somehow remains innocent in the eyes of the beholder. Daily he works at the post office behind the glass and in the evening he studies languages. But he’s continually drawn to this lady across the way. He feels like he knows her. He wants any pretense to meet her and so he creates a bit of fate anytime he can. However, often times sex and love become synonymous terms and that is the underlying tension between Tomek and Maria Magdelena’s relationship. Though innocent, he wants true love, a love that transcends a simple physical act and is summed up with affection, intimacy, and an inherent closeness. He is taken with her beauty certainly but even more so he is invariably alone. Meanwhile, she is so enraptured with sex and denigrating such a grand (and admittedly messy) thing as love, to a simple physical act. She can’t understand this wide-eyed boy and his delusions. She’s ready to open him up to the way the world actually turns. And her callousness ultimately crushes Tomek’s tender heart. She broke it not by simply rejecting him, because this is a ludicrous love story, but truly obliterating any of the naive aspirations he had for love.

However, often times sex and love become synonymous terms and that is the underlying tension between Tomek and Maria Magdelena’s relationship. Though innocent, he wants true love, a love that transcends a simple physical act and is summed up with affection, intimacy, and an inherent closeness. He is taken with her beauty certainly but even more so he is invariably alone. Meanwhile, she is so enraptured with sex and denigrating such a grand (and admittedly messy) thing as love, to a simple physical act. She can’t understand this wide-eyed boy and his delusions. She’s ready to open him up to the way the world actually turns. And her callousness ultimately crushes Tomek’s tender heart. She broke it not by simply rejecting him, because this is a ludicrous love story, but truly obliterating any of the naive aspirations he had for love. There is no solitude greater than that of the samurai unless it be that of a tiger in the jungle… perhaps…

There is no solitude greater than that of the samurai unless it be that of a tiger in the jungle… perhaps… And though he does call on his lovely girlfriend (Nathalie Delon), who is absolutely devoted to him, as well as making eyes at the nightclub pianist who is the main eyewitness to his hit, Jef for all intent and purposes, is alone. It’s a kind of forced solitude, a self-made exile created by his trade. After he goes through with the hit, he must shut himself off more and more. That is his job.

And though he does call on his lovely girlfriend (Nathalie Delon), who is absolutely devoted to him, as well as making eyes at the nightclub pianist who is the main eyewitness to his hit, Jef for all intent and purposes, is alone. It’s a kind of forced solitude, a self-made exile created by his trade. After he goes through with the hit, he must shut himself off more and more. That is his job.

Robert Bresson’s film is an extraordinary, melancholy tale of adolescence and as is his customs he tells his story with an assured, no-frills approach that is nevertheless deeply impactful.

Robert Bresson’s film is an extraordinary, melancholy tale of adolescence and as is his customs he tells his story with an assured, no-frills approach that is nevertheless deeply impactful. I’ve heard people like director Jean-Pierre Gorin say that there is little to no distinction between documentary and fiction. At first, it strikes us as a curiously false statement. But after giving it a moment of thought it actually makes sense, because no matter the intention behind it, the medium of film is always subjective. It’s always a created reality that’s inherently false and even in its attempts at realism — that realism is still constructed.

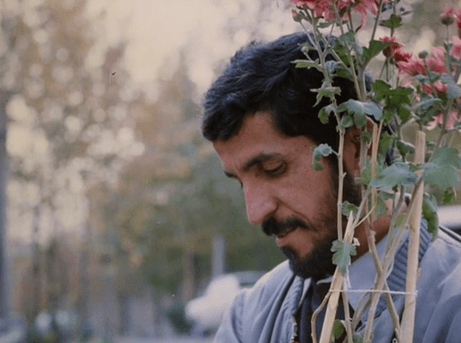

I’ve heard people like director Jean-Pierre Gorin say that there is little to no distinction between documentary and fiction. At first, it strikes us as a curiously false statement. But after giving it a moment of thought it actually makes sense, because no matter the intention behind it, the medium of film is always subjective. It’s always a created reality that’s inherently false and even in its attempts at realism — that realism is still constructed. The beauty of Close-Up that not only does it feature the real individuals involved in this whole ordeal: There’s Sabzian playing himself, the Ahankhah family who brought the case to court, and Kiarostami appearing as well. But it blends the actual footage from the trial with reenacted scenes set up by the director as if they are happening for the first time.

The beauty of Close-Up that not only does it feature the real individuals involved in this whole ordeal: There’s Sabzian playing himself, the Ahankhah family who brought the case to court, and Kiarostami appearing as well. But it blends the actual footage from the trial with reenacted scenes set up by the director as if they are happening for the first time. At face value, Model Shop is an ordinary film of little consequence but look a little deeper and it’s actually a fascinating portrait of the L.A. milieu in 1969. Part of that is due to the man behind it all.

At face value, Model Shop is an ordinary film of little consequence but look a little deeper and it’s actually a fascinating portrait of the L.A. milieu in 1969. Part of that is due to the man behind it all. John Donne is noted for writing that no man is an island, but if this film is any indication, there might be a need to qualify that statement to suggest that some women are islands — at least when portrayed by the elegiac Monica Vitti. Red Desert begins with blurred images and a high-pitched piercing melody playing over the credits. From its opening moments, two things are evident. It gives off the general sense of industry and it features one of the most extraordinary uses of color ever with the blues and grays contrasting sharply with the brighter pigments.

John Donne is noted for writing that no man is an island, but if this film is any indication, there might be a need to qualify that statement to suggest that some women are islands — at least when portrayed by the elegiac Monica Vitti. Red Desert begins with blurred images and a high-pitched piercing melody playing over the credits. From its opening moments, two things are evident. It gives off the general sense of industry and it features one of the most extraordinary uses of color ever with the blues and grays contrasting sharply with the brighter pigments. However, even if this word does reflect its share of beauty, it is Monica Vitti’s character who still embodies paranoia and disorientation with the modern civilization. In other words, she is the one out of step with the contemporary world that she finds herself in, due in part to an auto accident and a subsequent stint in a hospital. She is struggling to readjust to reality.

However, even if this word does reflect its share of beauty, it is Monica Vitti’s character who still embodies paranoia and disorientation with the modern civilization. In other words, she is the one out of step with the contemporary world that she finds herself in, due in part to an auto accident and a subsequent stint in a hospital. She is struggling to readjust to reality. As per usual with Antonioni, his film invariably feels to be altogether more preoccupied with form over content and that’s what is most interesting. It’s fascinating some of the environments he develops. Atmospheres full of billowing fog, wispy trees, stark alleyways, gridiron structures, and all the while the color red pops in every sequence. There’s no score in the typical sense, instead, the dialogue is backed by foghorns, machinery, and an occasional electronic sound effect.

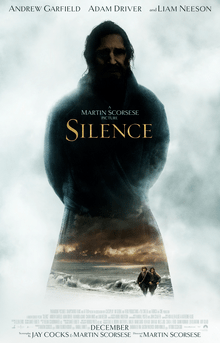

As per usual with Antonioni, his film invariably feels to be altogether more preoccupied with form over content and that’s what is most interesting. It’s fascinating some of the environments he develops. Atmospheres full of billowing fog, wispy trees, stark alleyways, gridiron structures, and all the while the color red pops in every sequence. There’s no score in the typical sense, instead, the dialogue is backed by foghorns, machinery, and an occasional electronic sound effect. If we can take Martin Scorsese’s varied film career as a reflection of the human experience, then his completion of his long-awaited passion project Silence is not all that surprising. He’s crafted numerous classics, countless cultural touchstones, some spiritual, some historical, and some incredibly honest. But at this point in his career it seems like he has nothing left to prove to us as his audience and maybe at this point in life, if nothing else, we could do well to try and learn from someone like him. Because given the climate with funding and the like, Scorsese could not have made such a film just for other people or money or acclaim. He must have made it, at least partially, for himself.

If we can take Martin Scorsese’s varied film career as a reflection of the human experience, then his completion of his long-awaited passion project Silence is not all that surprising. He’s crafted numerous classics, countless cultural touchstones, some spiritual, some historical, and some incredibly honest. But at this point in his career it seems like he has nothing left to prove to us as his audience and maybe at this point in life, if nothing else, we could do well to try and learn from someone like him. Because given the climate with funding and the like, Scorsese could not have made such a film just for other people or money or acclaim. He must have made it, at least partially, for himself.