It’s fascinating how history works. Deanna Durbin and Judy Garland came up at the same time. In their day, stars were groomed from an early age and MGM had both the starlets under contract. But instead of holding onto both talents it turned out that Garland remained and Durbin signed a new agreement with Universal.

The conventional wisdom was that you only needed one young singing girl at a studio. That niche was filled. Of course, that proved to be far from the truth as Durbin became a smash hit in her own right rivaling Garland.

100 Men and a Girl is only one film in a long list of successful outings she had in the 1930s starting with Three Smart Girls (1936). Most of these pictures were directed by Henry Koster and proved very popular with audiences.

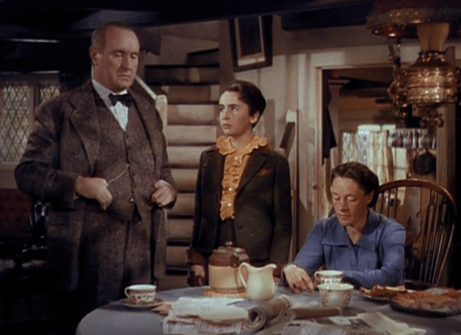

This particular one surrounds Durbin with players including Adolph Menjou and has some My Man Godfrey (1936) castmates carried over from the previous year. There’s the inclusion of flabbergasted Billy Gilbert as the easily duped funnyman and other crucial character actors like Mischa Auer and Frank Jenks taking up posts as a flutist and a stymied cabbie respectively.

But front and center and most agreeable of everyone is this pleasant girl who unwittingly finds herself in high society and taken under the wing of a bubbly socialite (Alice Brady), who finds this girl’s demeanor charming perhaps for the very fact that she’s so sweet and well, a frantic force of nature. It’s delightfully refreshing and different from the snooty company the lady is used to having in her presence.

But Patsy Cardell can also sing quite stupendously and that’s to her credit. I’m hardly musically inclined but Durbin even at this age hardly seems a show tunes singer, sweetly navigating the utmost of classical compositions with a voice that feels beyond her years. My personal tastes are simpler but there’s no discounting her vocal abilities.

Still, the film is born out of an admittedly absurd idea and the light bulb flashes in a rapid burst of inspiration. Patsy’s father (Menjou) is out of work and so are 100 of his fellow musicians. What should she do? Starting a symphony orchestra is what she should do! It’s as clear as day and she motors forward determined to make her idea turn into something tangible with the promise of backing from Mrs. Frost (Brady).

The wind is in her sails and she’s not about to allow logistics or the scorn of others uproot her vision. Her goal is to get her daddy on Mr. John R. Frost’s radio show. It’s just what her father needs to get back to work. Presto! This is a film plot that might as well have gotten resolved with a puff of smoke. Just like that. Instead, she is crushed by the curmudgeon husband (Eugene Pallette), his wife now off in Europe out of sight. So Patsy has no recourse to go to the top and famed conductor Leopold Stokowski (playing himself).

The rest of the story relies on a number of convenient happenstances. False hopes and crushed dreams become real hopes and true dreams. Although it’s a pure pipe dream of a film, sometimes that’s just what we need whether we’re still wrangling with the Great Depression or in the here and now 80 years onward. Because films like this that are ethereal, fluffy, and light still give us something.

Durbin holds her own with cheerfulness and a certain amount of sass that doesn’t compromise her basic principles. She was instantly likable in her day and still much the same today.

Henry Koster will never get any respect for the kind of pictures that he made but that’s okay because he made films that were crafted with a genuine heart. That speaks to people in ways that other types of films can’t seem to manage. True, this picture can hardly claim the title of an artistic masterpiece for critics to fawn over and dissect to death with their immaculate vocabulary and academic analyses. That too is okay. Here is a film that’s wacky, fun, and it’s okay with being just that.

Deanna Durbin was credited with saving her studio from the pits of bankruptcy during the depression years with her voice and her spirit and a certain candor that made her a beloved girl-next-door icon for a generation. She was crystallized in that image and never quite broke out like she probably would have liked.

She also never saw the same acclaim from modern generations like a Judy Garland since she didn’t have a film like The Wizard of Oz (1939) for folks to rally around but in her time she was quite the attraction. All told, finding her again today is still a lovely revelation. She remains enjoyable to watch even for nostalgia’s sake. Sometimes that’s enough.

3.5/5 Stars

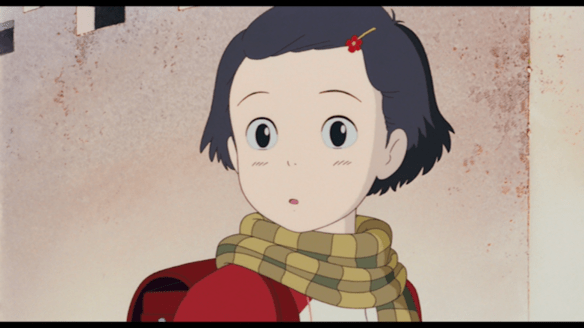

The song “Sukiyaki” sung by Kyu Sakamoto proved such a charming enigma for me. Here was a record that was so quintessentially Japanese, a melodious ballad, that was nevertheless branded in the West with a more novel title and became a smash hit. However, here within the framework of this anime, the song feels perfectly at home once more as “Ue o Muite Arukō” an impeccable benchmark of an era in Japan’s history. It’s true that the full extent of the musical score is noticeably more western than we might be used to with anime yet the cornerstone of the soundtrack is Sakamoto’s iconic tune.

The song “Sukiyaki” sung by Kyu Sakamoto proved such a charming enigma for me. Here was a record that was so quintessentially Japanese, a melodious ballad, that was nevertheless branded in the West with a more novel title and became a smash hit. However, here within the framework of this anime, the song feels perfectly at home once more as “Ue o Muite Arukō” an impeccable benchmark of an era in Japan’s history. It’s true that the full extent of the musical score is noticeably more western than we might be used to with anime yet the cornerstone of the soundtrack is Sakamoto’s iconic tune.

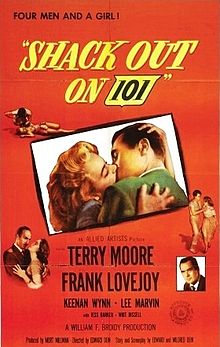

Like a Cry Danger (1951) or a Private Hell 36 (1954), this low budget film noir flick is such a joy to watch because it wears what it is right on its sleeve, clear out in the open. What we get is an utterly absurd paranoia thriller that also happens to be a heaping plate of B-noir fun.

Like a Cry Danger (1951) or a Private Hell 36 (1954), this low budget film noir flick is such a joy to watch because it wears what it is right on its sleeve, clear out in the open. What we get is an utterly absurd paranoia thriller that also happens to be a heaping plate of B-noir fun.