For some Black Panther might be a stellar actioner, consequently, brought to us by a visionary director, Ryan Coogler. It’s top-tier as far as Marvel movies come; there’s little doubt. For others, I completely understand if Black Panther rocks their entire paradigm because there’s so much of note here. The box office seems to confirm that just as much as the dialogue that has been created in its wake.

For some Black Panther might be a stellar actioner, consequently, brought to us by a visionary director, Ryan Coogler. It’s top-tier as far as Marvel movies come; there’s little doubt. For others, I completely understand if Black Panther rocks their entire paradigm because there’s so much of note here. The box office seems to confirm that just as much as the dialogue that has been created in its wake.

What’s so revolutionary about this addition to the cinematic landscape is that this is not simply a superhero movie created by a predominantly black cast and crew but that their very heritage is so crucial to the roots of the story. The identity and complex history of Africans and African-Americans is wrapped up in the very sinews of the narrative. A whole diverse patchwork of ancestry and generations of culture is meticulously infused into the African nation of Wakanda.

Many may have forgotten that in an earlier Marvel installment the king of the 3rd world nation of Wakanda was killed in an act of terrorism. His son T’Challa proved to be next in line to the throne as long as no challengers arose from any of the five tribes that encompass the country. In such a case the two warriors take part in a ritual combat.

Far from just having intricate primordial traditions, the nation has also long-harbored an immense secret. Under the pretense of an archaic nation, they have built a technologically advanced empire around the versatile metal vibranium. In order to keep its properties protected, they have foregone sharing it with the world at large. Already you begin to see one of the primary themes running through the film. With great power comes great responsibility. How you choose to wield it is of vital importance especially when the world around you is hurting.

I have long been a fan of Ryan Coogler and Michael B. Jordan and the partnership continues to impress. Coogler somehow managed to take a Marvel franchise film (which we’ve had too many of) and turned it into a radically personal picture. It works on both levels — arguably catering to all audiences.

His female characters are imbued with tenacity and still a capacity for great good. Lupita Nyong’go is a perfect example as the lifelong sweetheart of the ascending king T’Challa because she has left her homeland to help the oppressed in less fortunate lands. She jokes that she would make a phenomenal queen one day because she’s stubborn but it’s the truth.

Meanwhile, the king’s mother (Angela Basset) is stately; caring deeply for her children while his sister (Letitia Wright) is feisty and blessed with the ingenuity of an inventor. She’s the Wakandan Q if you will. And there’s Okoye (Danai Gurira) the fearless leader of the all-female royal guard. Far more than an assassin, she is guided by a sense of honor and loyalty that splits her right down the middle.

Many people will be happily surprised by a soundtrack that synthesizes original music by Kendrick Lamar with a score by Ludwig Goranson (Community) infused with distinctly African instrumentation. It makes for a satisfying marriage in music. But no less impressive are the intricate costumes and set designs which develop this appealing aesthetic of the old with the new. Coogler’s team seems to have a very keen awareness of both which is refreshing.

When Black Panther falters at all the problem is simply due to repetition. After 17 other entries, we can hardly blame a film like this for doing something that’s seemingly derivative even momentarily. It’s inevitable. Because if you’ve seen one fight scene between two agile, armored superhumans you’ve seen them all to some extent.

And yet this picture does so much more within that framework that’s moving because there’s a certain ambition and an innate understanding of what movies are capable of. They can help us cull through crises while still maintaining the exhilarating guise of a superhero action flick. It’s true that at times it feels like we are watching a Bond film only rejuvenated with more diverse characterization.

Like the best films in that franchise or any other really, the villains are noticeably tempered in a very particular way that is stimulating. Yes, multiple bad guys, and when I say that I mean that each has unique shading giving us different looks. Andy Serkis is the chortling international arms dealer who seems small scale and yet he’s made dangerous. There’s a distinct edge to him.

Even more important is Erik Warmonger (Michael B. Jordan) because he acts as T’Challa’s character foil. As we find out, they have a lot more in common than they would have been led to believe except Warmonger has more sinister intentions. The joy of Jordan’s performance is that the character is high-functioning, charismatic, and actually poses a threat as we see on multiple occasions. But no matter how twisted or misguided he might seem there’s still some level on which we can understand his lifelong resentment. Also, let me just say it now. From his clothes to his swagger, he just looks cool…and supremely confident.

Meanwhile, fellow tribesmen such as M’Baku (Winston Duke) and W’Kabi (Daniel Kaluuya) do not necessarily have sworn allegiances staked out and so that gives them some agency to shift the tectonics of the story this way or that. Again, they have a certain amount of power that gives them an undeniable presence.

Like The Winter Soldier or Civil War (arguably my favorite Marvel entries thus far), the villains are compelling because they invariably feel planted in the real world or better yet they’re made up of friends and family. There’s nothing more disconcerting than people who aren’t villains at all and yet they still go in opposition of you.

Thus, Ryan Coogler has succeeded in constructing a layered story that might be one of the few Marvel films I would gladly pay a second viewing to. It hinges on so many issues with consequences for our contemporary landscape. Again, with great power comes great responsibility.

It deals with the afterlife as represented by the ancestral hunting grounds where first T`Challa and then Erik commune with their fathers to receive insight. For the former, it means reconciling with his father’s own failures during his lifetime so he might not make the same mistake. For the latter, it means connecting with his own father about their joint Wakandan heritage which Erik never knew first-hand living in America.

Black Panther calls into question themes of isolationism as much as it does a complicated history of colonialism. Look no further than the African artifacts exhibit in the History Museum and you can plainly see that we are still grappling with the same issues planted in the same past. Far from dismissing it, we would do well to continue to entertain a dialogue. The roles that museums, archivists, and archaeologists play in all of this are important too. Suddenly, even for a brief instant, I’m starting to second-guess Indy’s obdurate assertion that artifacts belong in a museum. Where do we draw the lines on such an issue while not unwittingly promoting colonialist traditions? I don’t quite know.

The final words of Warmonger linger in my mind as well:

T`Challa: “We can still heal you…”

Warmonger: “Why, so you can lock me up? Nah. Just bury me in the ocean with my ancestors who jumped from ships, ’cause they knew death was better than bondage.”

His words sting, as they should because so much truth dwells right there. I have always struggled to reconcile those very things because for being a nation made of immigrants the African-Americans are nearly the only ones who did not come to The Promise Land of their own volition. The handprints of such a reality can still be spotted in our world today.

There are deep roots that are set in place. In the History Museum corridors, you see documentation of a muddied past of colonialism. Then, in Oakland (Coogler’s hometown) along with basketball and Public Enemy you see obvious signs of social decay and problematic issues of drugs and gun violence.

The fact this is actually put out there is nearly a relief and a necessity. However, and this is a big however, there seems to be an underlying hopefulness that we can somehow live together. Marcus Garvey once proposed blacks recolonize their native country and that in itself brings up other issues of cultural identity.

Erik Warmonger is right at the center of that with African descent and yet longheld ties to American society. What do we label him? I’m not sure we can. I’m not sure we need to. That’s for the individual. Regardless, it’s a work in progress. Messy no doubt but hope is still present.

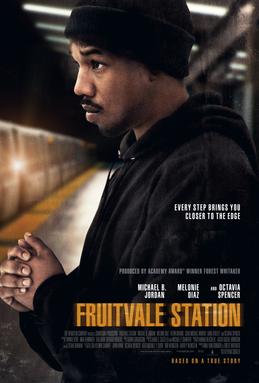

Like Fruitvale Station (2013) before it, being rich in black culture by no means suggests that the film is completely exclusive in the same regard. Far from simply being a token white person, Martin Freeman is allowed to be a hero just like his counterparts, and anyways maybe for once, it’s okay for the Caucasian characters to take a momentary back seat if only to allow other voices to speak.

What we are left with as King T’Chala addresses the United Nations is not the sense that one people group is better than another or the new should overthrow those who have long been in power but that we should find those points of intersection — the things that unify us.

“Now, more than ever, the illusions of division threaten our very existence. We all know the truth: more connects us than separates us. But in times of crisis the wise build bridges, while the foolish build barriers. We must find a way to look after one another, as if we were one single tribe.”

It’s a fitting summation because this is a film that draws up different tribes, turns people against each other nearly in an instant, while constantly rearranging factions and who holds the keys to the kingdom. If it’s resolved in the end it’s only a fragile peace at best and if we are to maintain that we need far more than vibranium. We need a heavy dose of human understanding and empathy.

We can acknowledge our past failures as a society but must never allow them to shackle us for good. Mistakes are meant to be learned from. It’s when we’re not willing to learn and to change, that dire straits look inevitable. I hope for our sake that the film’s call-to-action might still stand true.

But the film itself is also an imperative to take deep abiding pride in your heritage and who you are as a human being — unique just as you are. Thus, it seems utterly misguided to desire a future world where we do not see color. Instead, we might yearn for a day when everyone can look at the rich strains of human diversity and proclaim “It is very good.” Where we can survey that same world and see that every color, creed, and tongue is finally one tribe instead of many.

4/5 Stars

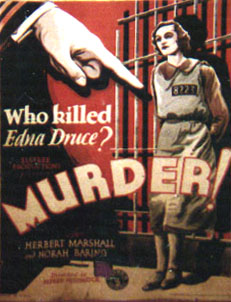

Alfred Hitchcock captures the pure bedlam that overtakes a neighborhood when their peaceful dreams are rudely disrupted by an awful din. As is customary everyone is in a foul mood, peers out their windows, bickers with everyone else, and moves into action.

Alfred Hitchcock captures the pure bedlam that overtakes a neighborhood when their peaceful dreams are rudely disrupted by an awful din. As is customary everyone is in a foul mood, peers out their windows, bickers with everyone else, and moves into action.

It only serves to show where my mind goes when I watch a movie. I couldn’t help but think of Harry Chapin’s elegiac and stirringly heart-wrenching tune “Mr. Tanner” as I was ambushed with some of the most revelatory notes of Coco. The most meaningful line out of that song relates how music made our eponymous hero “whole.” I feel the same guttural satisfaction blooming out of this picture.

It only serves to show where my mind goes when I watch a movie. I couldn’t help but think of Harry Chapin’s elegiac and stirringly heart-wrenching tune “Mr. Tanner” as I was ambushed with some of the most revelatory notes of Coco. The most meaningful line out of that song relates how music made our eponymous hero “whole.” I feel the same guttural satisfaction blooming out of this picture. For some Black Panther might be a stellar actioner, consequently, brought to us by a visionary director, Ryan Coogler. It’s top-tier as far as Marvel movies come; there’s little doubt. For others, I completely understand if Black Panther rocks their entire paradigm because there’s so much of note here. The box office seems to confirm that just as much as the dialogue that has been created in its wake.

For some Black Panther might be a stellar actioner, consequently, brought to us by a visionary director, Ryan Coogler. It’s top-tier as far as Marvel movies come; there’s little doubt. For others, I completely understand if Black Panther rocks their entire paradigm because there’s so much of note here. The box office seems to confirm that just as much as the dialogue that has been created in its wake. Ryan Coogler is from Oakland, California. He was attending USC Film School in 2009 when Oscar Grant III was shot near the BART station. From those experiences were born his first project. He envisioned Michael B. Jordan in the lead role. Thankfully his vision and the casting came to fruition.

Ryan Coogler is from Oakland, California. He was attending USC Film School in 2009 when Oscar Grant III was shot near the BART station. From those experiences were born his first project. He envisioned Michael B. Jordan in the lead role. Thankfully his vision and the casting came to fruition. “You can fool all of the people some of the time, you can even fool some of the people all the time, but you can’t fool all the people all the time.” ~ Inscription in the Fortune Cookie

“You can fool all of the people some of the time, you can even fool some of the people all the time, but you can’t fool all the people all the time.” ~ Inscription in the Fortune Cookie In one sense Blackmail proves to be a landmark in simple film history terms but it’s also a surprisingly frank picture that Hitchcock injects with his flourishing technical skills. It’s of the utmost importance to cinema itself because it literally stands at the crossroads of silent and talking pictures and holds the distinction of being one of Britain’s first talkies.

In one sense Blackmail proves to be a landmark in simple film history terms but it’s also a surprisingly frank picture that Hitchcock injects with his flourishing technical skills. It’s of the utmost importance to cinema itself because it literally stands at the crossroads of silent and talking pictures and holds the distinction of being one of Britain’s first talkies. What’s striking about Alfred Hitchcock is the sheer breadth of his work and how his career managed to take him in so many directions as he continued to evolve and experiment with his craft from silent pictures, to talkies, then Hollywood, and all the way into the modern blockbuster age. And yet the very expansiveness of his oeuvre begs the question, where to begin with it all? Certainly, his lineup of masterpieces in the 1950s are a must.

What’s striking about Alfred Hitchcock is the sheer breadth of his work and how his career managed to take him in so many directions as he continued to evolve and experiment with his craft from silent pictures, to talkies, then Hollywood, and all the way into the modern blockbuster age. And yet the very expansiveness of his oeuvre begs the question, where to begin with it all? Certainly, his lineup of masterpieces in the 1950s are a must.

My heart lept in my chest when I heard that Taika Watiti (What We Do in The Shadows) was going to be helming the latest Thor movie. Because it’s hardly a well-kept secret that Thor has essentially been the weakest of all the Marvel threads (Hulk’s individual film excluded).

My heart lept in my chest when I heard that Taika Watiti (What We Do in The Shadows) was going to be helming the latest Thor movie. Because it’s hardly a well-kept secret that Thor has essentially been the weakest of all the Marvel threads (Hulk’s individual film excluded).