Granted you have star power but it’s easy to assume that The Big Steal will be a no name picture. A minor triumph at best. Not so! This film fares far better than countless of its bigger competitors.

It proves to be a winking romp full of bedroom brawls, car chases, and twists and turns every which way that send us whipping through Mexico. Equally important to the pace of the action is the levity of the script from Daniel Mainwaring (under a pseudonym) that gives our stars something to do and they do it effortlessly.

Robert Mitchum and Jane Greer (partnered again after the undisputed classic Out of the Past) meet as the two obvious foreigners in a sea of locals as Mitchum is getting accosted by a street vendor to buy a parrot. He’s one of those foreigners coming off as a buffoon navigating other cultures and the languages that go with them. Though I can’t ride him too hard as one of those blundering Americans myself. Still, his Spanish is mediocre at best and she is aghast at his cultural insensitivity. So right there you have the needed romantic tension and things only get better going forward.

Because their association doesn’t end there. Of course, it doesn’t. Duke Halladay is out to nab the man named Fiske (Patric Knowles) who absconded with some of his hard earned cash and Joan had a similar job pulled on her — the man of questionable integrity also just happened to be her boyfriend.

The unlikely partnership is formed after Mitchum leaps for the running board of the other man’s fleeing vehicle and winds up dragging Greer in front of the Inspector General to explain the public disturbance.

The Inspector General (Ramon Novarro) happens to be a budding pupil in English as his second in command (Don Alvarado) attended the University of California which while being convenient for the story also manages to make our Mexican characters into actual individuals who are endowed with an animated quality all their own.

If the main chase is our leading couple trying to track down Fiske, who gives them the slip on multiple occasions then the scenario simply gets more convoluted as Duke’s superior (William Bendix) is tailing him. They have some unfinished business to attend to because Blake believes the other man took part in a theft of his own. Thus, The Big Steal is just that. Even the soft-spoken John Qualen (probably best remembered for Casablanca) gets in on the party and flaunts a bit of a villainous side.

Some of the finer moments are the lighter ones. There’s the ongoing patter of the dialogue firing off between Mitchum and Greer which couldn’t be better and it comes from the days where a guy could call a dame “Chaquita” and it’d stick. But the beauty of their relationship is Greer with that quizzical look of hers can dish it right back in Mitchum’s direction.

Likewise, during a winding car chase, the same character can quite seriously exclaim “Watch out for the cow” only to turn right around and create a livestock blockade of his own. Or because we are in rural Mexico cars can get stuck behind a caravan of hay wagons ambling along leisurely. They have no respect for the drama at stake. On another note, I’m flabbergasted that the cars involved survived at all with the dubious amount of off-roading they managed. I guess in the 1940s they built things to last.

There’s one hilarious roadblock in particular where Jane Greer uses her Spanish and Mitchum’s obliviousness to tell a local road worker (Pascual Garcia Pena) that they are madly in love and running away from her disapproving father. They must get through at all costs and it just so happens that Captain Blake is right behind him and receives a fine welcoming committee.

But the key is that the film ends not on the downward plunge but on the upswing as our two lovebirds observe the local mating rituals and give it their own twist. What a great picture and sure, it’s no Out of the Past but no one needs it to be. We already have one of those and The Big Steal is a leisure ride of its own making.

Set this against a backdrop beyond the Mexico border, a spliced together version of on location atmospherics and studio shots, and you are blessed with the wonderful patchwork of authenticity and artificiality that old Hollywood was known for in the 40s and 50s.

What’s more fascinating is that The Big Steal at least in this form might never have been. Robert Mitchum was hot off his notorious jailtime term because of marijuana possession, an event that undoubtedly solidified his reputation as an antihero. Meanwhile, not too happy with Jane Greer, RKO studio head and temperamental mogul Howard Hughes gave her this role out of spite.

How could a picture this small be any good with a leading man saddled with bad publicity? I cannot speak to contemporary audiences but today The Big Steal plays quite well. We have our stars and screenwriter to thank as well as a young up and coming director named Don Siegel who started out as a montage man and transitioned into B-pictures.

What makes him a wonderful worksmith is how he always seems to have a pulse on the action and he turns situations into truly dynamic entertainment even when it’s on a small scale. He didn’t need a big budget to still make a rip-roaring good time. The Big Steal is a stellar testament to what the Classic Hollywood studios were capable of with meager means. It’s an absorbing effort.

4/5 Stars

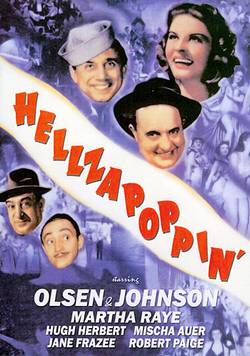

It essentially begins with a fourth wall break. That’s all you need to know. Because that gives you exactly an idea of what you’re in for with Hellzapoppin’ or rather it gives you no idea whatsoever what you’re in for but really they’re one in the same. I’ve seen the movie and I still don’t quite know what it was.

It essentially begins with a fourth wall break. That’s all you need to know. Because that gives you exactly an idea of what you’re in for with Hellzapoppin’ or rather it gives you no idea whatsoever what you’re in for but really they’re one in the same. I’ve seen the movie and I still don’t quite know what it was. In style if not entirely in execution The Lineup exhibits some similarities to Murder by Contract from the same year. Both films choose to take hit men as their main characters and it becomes a surprisingly intriguing way to look at a crime. Because the killers are a certain brand of sociopath who make film criminals all the more compelling based on not only on the way they carry themselves or the actions they take but the very words that leave their lips.

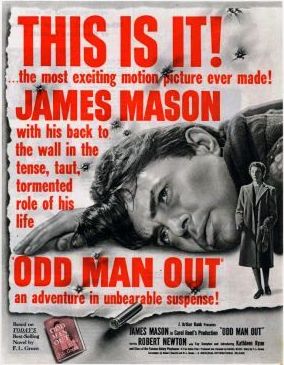

In style if not entirely in execution The Lineup exhibits some similarities to Murder by Contract from the same year. Both films choose to take hit men as their main characters and it becomes a surprisingly intriguing way to look at a crime. Because the killers are a certain brand of sociopath who make film criminals all the more compelling based on not only on the way they carry themselves or the actions they take but the very words that leave their lips. In my profession, there is neither good nor bad. There is innocence and guilt. That’s all. ~ Denis O’Dea as the Police Inspector

In my profession, there is neither good nor bad. There is innocence and guilt. That’s all. ~ Denis O’Dea as the Police Inspector

Patterns has little right to be any good. It takes place almost exclusively in interiors. Boardrooms, offices, hallways, at desks, and in elevators. But thanks to a fantastic teleplay from Twilight Zone mastermind Rod Serling, this little picture exceeds the meager expectations placed on it. In fact, it was a major hit when it came out as a live television drama, so successful that it was performed a second time and subsequently developed into this film version.

Patterns has little right to be any good. It takes place almost exclusively in interiors. Boardrooms, offices, hallways, at desks, and in elevators. But thanks to a fantastic teleplay from Twilight Zone mastermind Rod Serling, this little picture exceeds the meager expectations placed on it. In fact, it was a major hit when it came out as a live television drama, so successful that it was performed a second time and subsequently developed into this film version. Whatever our criticisms of the previous generations, there’s still something within me that sees something uniquely compelling about films of old. Hollywood in the 30s and 40s could sugar coat, they could oversell the drama, but there was also a general decency that pervaded many of those films.

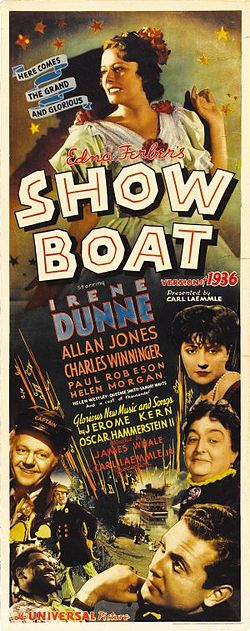

Whatever our criticisms of the previous generations, there’s still something within me that sees something uniquely compelling about films of old. Hollywood in the 30s and 40s could sugar coat, they could oversell the drama, but there was also a general decency that pervaded many of those films. Most of what I know about riverboats can be gleaned from Mark Twain, Davy Crockett and the River Pirates, and that ever beloved Snoopy incarnation The World Famous River Boat Gambler. The 1936 musical Show Boat falls into that very same rich tradition but some clarification is in order.

Most of what I know about riverboats can be gleaned from Mark Twain, Davy Crockett and the River Pirates, and that ever beloved Snoopy incarnation The World Famous River Boat Gambler. The 1936 musical Show Boat falls into that very same rich tradition but some clarification is in order. Like the fella says, in Italy for 30 years under the Borgias they had warfare, terror, murder, and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and the Renaissance. In Switzerland they had brotherly love – they had 500 years of democracy and peace, and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.

Like the fella says, in Italy for 30 years under the Borgias they had warfare, terror, murder, and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and the Renaissance. In Switzerland they had brotherly love – they had 500 years of democracy and peace, and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.  Joseph Cotten is surprisingly compelling as the poor, unfortunate stiff and it’s hard not to feel sorry for him in his ignorance because we can relate with him. Alida Valli is striking as the aloof beauty who nevertheless has an unswerving affection for her former love that remains the only joyous thing in her current existence. Then, of course, there’s Orson Welles as the charismatic myth of a man–arguably the most intriguing supporting character there ever was even if it’s mostly thanks to the legend created by those who knew him.

Joseph Cotten is surprisingly compelling as the poor, unfortunate stiff and it’s hard not to feel sorry for him in his ignorance because we can relate with him. Alida Valli is striking as the aloof beauty who nevertheless has an unswerving affection for her former love that remains the only joyous thing in her current existence. Then, of course, there’s Orson Welles as the charismatic myth of a man–arguably the most intriguing supporting character there ever was even if it’s mostly thanks to the legend created by those who knew him.