The premise of The Visitor is born in a rapid succession of images and shots. It’s a meet-cute correspondence so-to-speak as an attractive young woman venturing into her 30s looks to find an eligible man to invite into her home on some kind of ill-defined get-to-know-you basis.

It would not be possible without an advert in a newspaper fishing for a husband who meets certain basic qualifications. It’s not quite a blind date, but it might as well be. It somehow feels akin to the hook-up, internet, online dating culture we are awash in during the 21st century. At least, this is the 1960s alternative.

But lest one gets the wrong impression, it also feels a bit like 84 Charing Cross Road, except there is no pretense of books. They’re two lonely people looking to get together with someone for the sake of companionship. If they’ve read the Good Book, they know it’s not good for man (or woman) to be alone.

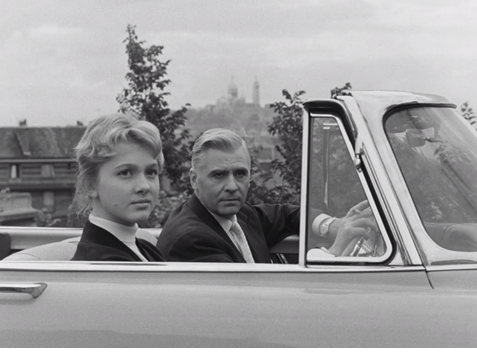

The pretty single woman, Pina, waits for the train from Rome bringing her mystery man. Sandra Milo though still her beautiful self all but transforms into a different woman than most are normally accustomed from her in anything from the director’s earlier Adua or Fellini’s 8 1/2.

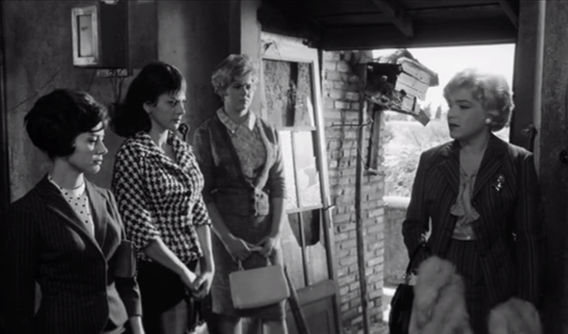

If you’ve seen anything from Divorce Italian Style to Two Women, you might not be totally surprised (or scandalized) by the misogyny, but somehow it never feels right because it reflects the lustful intent in the collective hearts of men. It’s not the actions that are most troubling; it is what they suggest about society-at-large. When the colloquial name for someone is “Miss Booty,” you realize the seat of the issue.

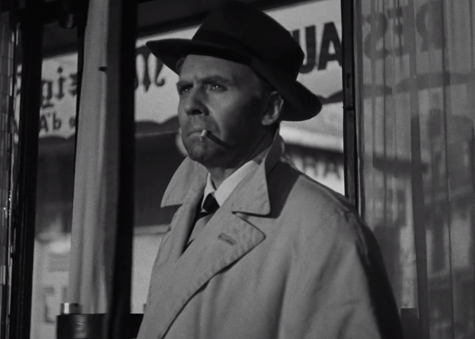

Because as Pina brings this bookish-looking fellow named Adolfo (Francois Perier) back to her humble abode, the cringe-worthy gaze of the camera — his gaze — continues to dictate the picture. What we have before us is obviously in the mode of so-called “Commedia all’italiana” or “comedy the Italian way.”

It’s the Italian spin on the sex comedy, which in Hollywood would look a bit more like Pillow Talk or at the very least Buona Sera Mrs. Campbell. And yet unlike Hollywood, there seems to be little narrative drive. The picture is contented to amble along, which can be both its greatest blessing and a defining curse.

At its best, it casts a sardonic eye at the fragilities and flaws running deep within Italian culture and certainly all its romantic dalliances. But there is a fine line between reveling in the passionate desires and simultaneously trivializing this pervasive trend in society. There’s an effort to try and smooth it over with humor.

The quirks are present in full force. A parrot sounding unmistakably like Donald Duck and a turtle named Consuelo. Local weirdos abound including an oafish peasant ready to throw jealous temper tantrums and get any sort of rise out of the visiting Roman that he can.

Throughout their courtship, recollections coming stream back whether it’s work — the purportedly well-off bookkeeper is actually hated by his boss. They’ve also maintained relationships in a laundromat and with an itinerant truck driver, respectively, never quite finding time to talk about their former lovers. Perhaps it just slips their minds…

Dinner provides another telling arena. As the man gets more comfortable with himself, we begin to see a bit more of who he is, especially piggish, gobbling away at her dinner and relishing in all the gluttony before him to satiate his appetite. Likewise, there’s the youthful siren (Angela Minervini) tugging at him, reminiscent of Marcello’s desires for Stefania Sandrelli in Divorce Italian Style.

Except there’s no lacquered pretense of suavity or manners — not really. The pudgy face, bespectacled lout is precisely that and his interactions with the flaunting girl prove painful to watch. This relationship with Chiaretta comes to a head at a gathering outdoors where all the teens and adults mingle over dance. The wheels fall off the cart. Pina is hurt and feels betrayed by her now uninhibited man. It doesn’t come out immediately. Still, it’s there.

Eventually, she lashes out at him, for his arrogance, his treatment of animals, and of people, including herself. She has a point, and don’t get me wrong; he’s completely deserving of her wrath. But if he gets berated, I might be deserving of a few choice words along with most everyone else. He woefully admits that this is what happens to one living alone. We cannot condone his behavior. It’s a sorry excuse and yet…the harrowing thing is how mundane he is in his substandard treatment of others.

Can we conveniently write them off as lonely, insignificant people trying to get by in the world? I’m not sure. Will we enter the insidious gray area of writing off his behavior or condoning it? It’s possible. I didn’t enjoy being subjected to the utter pitifulness of it all and I’m not sure if I’m ready to admit seeing some of their qualities reflected right back at me. We are not immune to the loneliness they feel. We see all their defects. Can we acknowledge our own?

This final question remains: Will they find their happiness or live a life weighed down by this sense of miserable drudgery? Redemption begins with not simply a change of actions but a change in heart. It always strikes me Italian-style comedy rarely seems possible without some manifestation of human tragedy. There’s no more human way to grapple with our own boorishness, our own misapprehensions, and our own inadequacies.

3/5 Stars

During the period of time I lived in Japan, I became acquainted with the works of Isao Takahata, and by that I mean I watched both

During the period of time I lived in Japan, I became acquainted with the works of Isao Takahata, and by that I mean I watched both

One could choose any number of labels to attempt categorizing Departures. It’s a film indebted to the rapturous compositions of the past. It shares elements akin to any police procedural ever made or for that matter, the veterinary antics from a British gem like All Creatures Great and Small.

One could choose any number of labels to attempt categorizing Departures. It’s a film indebted to the rapturous compositions of the past. It shares elements akin to any police procedural ever made or for that matter, the veterinary antics from a British gem like All Creatures Great and Small. Whisper of The Heart is wholeheartedly a Japanese anime and yet learning John Denver’s “Country Roads” holds a relatively substantial place in the plotline might catch some off guard. After all, as the metropolitan imagery establishes our setting, we hear a version of the song playing against the bevy of passersby, cars, and convenience stores.

Whisper of The Heart is wholeheartedly a Japanese anime and yet learning John Denver’s “Country Roads” holds a relatively substantial place in the plotline might catch some off guard. After all, as the metropolitan imagery establishes our setting, we hear a version of the song playing against the bevy of passersby, cars, and convenience stores.