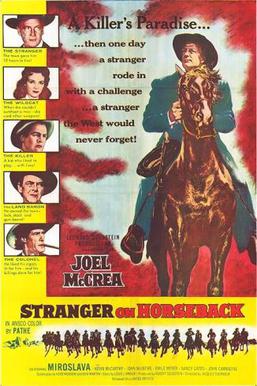

I didn’t know my Grandpa too well because he passed away when I was fairly young but I always remembered hearing that he really enjoyed reading Louis L’Amour. It’s not much but a telling statement nonetheless. I’ve read and seen Hondo (1953), which stars John Wayne and Geraldine Fitzgerald, and yet I’d readily proclaim Stranger on Horseback the finest movie adaptation of an L’Amour novel.

I didn’t know my Grandpa too well because he passed away when I was fairly young but I always remembered hearing that he really enjoyed reading Louis L’Amour. It’s not much but a telling statement nonetheless. I’ve read and seen Hondo (1953), which stars John Wayne and Geraldine Fitzgerald, and yet I’d readily proclaim Stranger on Horseback the finest movie adaptation of an L’Amour novel.

Exhibit A is Joel McCrea as a circuit judge, highly principled but firm in his dealings. He’s not simply an idealist either also having the guts to back up his philosophy, packing a gun and walloping thugs when it’s called for. He comes off as an irreproachable, unstoppable enactor of justice — a truly fascinating hero to stand front and center in a western.

Exhibit B has to be one of the most underrated directors of this period in Jacques Tourneur who not only showed an early penchant for low budget black and white horror but in a handful of color westerns, he showcased an equal affinity for visual filmmaking. Shot in Anscolor, Stranger on Horseback is quite the looker, encapsulating the 1950s western landscapes of old. No budget is too minuscule and no runtime too short for Tourneur to make an interesting picture.

The man rides past the unmistakable images of a pine box and a makeshift funeral. The dead man and the reasons for his death are still to be told. However, it becomes apparent very quickly that he was gunned down.

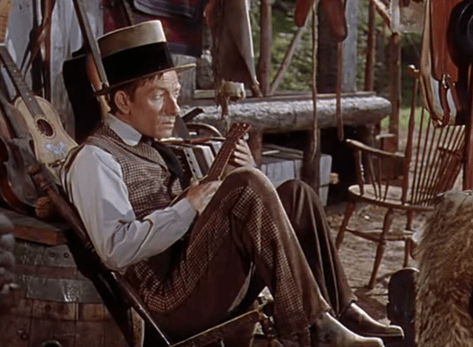

John Carradine leads the welcoming committee as the local attorney and stooge who is very conveniently on the Bannerman payroll and therefore in the family’s pocket. Because in a small place like this hidden away from the long arm of the national government, the Bannerman family and their associates remain king and they have their hand in everything.

The crotchety Josiah Bannerman (John McIntire) is looking to buy out the judge and invite him over to dinner to straighten him out about the killing that took place. He actually meets Judge Thorne and realizes full-well that’s not going to happen with such a principled man. For once there’s someone who isn’t afraid of him, even if he should be.

There’s his niece Amy Lee (Miroslava) who’s handy with a pistol and though she’s on the verge of marrying a feckless local boy, there’s a sense that he cannot give her anything. She is too strong like Bannerman. She needs a man who can match her self-assured toughness.

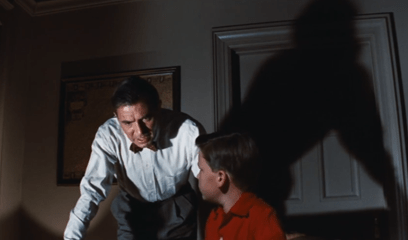

But it is Tom (Kevin McCarthy) the cocky, smart-aleck son who the judge forcibly takes to the local jailhouse to hold him for the murder of another man. Thorn’s put a target on his back and he knows that the retribution of Bannerman will come swiftly if he cannot be bought out.

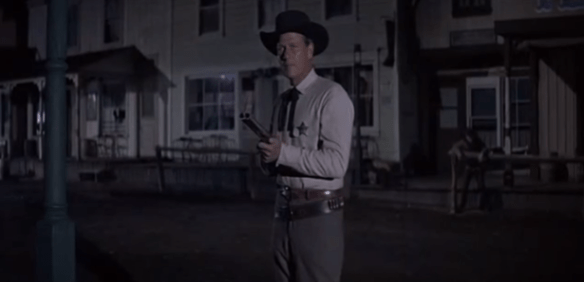

He gets the support of the local sheriff (Emile Meyer) who’s eager to shed the apathy that the town breeds and back a man with real guts who will stand by his gun. That’s attractive to him and so if no one else stands up, the Judge has one friend. Meanwhile, he rustles up a few clandestine witnesses to testify against the Bannerman boy because they saw what happened and though initially reluctant they agree to testify since it is the right thing.

With the nearest speck of civilization and with it the nearest courtroom being in the town of Cottonwood 47 miles away, it’s inevitable that Bannerman will send his cronies after the small caravan to stop them in their tracks. It looks to be a daunting proposition at best but again, the Judge never balks.

The finale is all but cut short on an abrupt even awkward note much as we suspected. Our hero has been met and his bluff has been called. But we soon realize since he has been a brazen and thoroughly scrupulous man thus far, he’s not about to change anytime soon. So the final outcomes might surprise just as much as they captivate in a mere matter of minutes.

The question remains, why does the judge go through all this trouble? Is it some vendetta that has him out for vengeance? Is he doing it to prove his stature or receive the admiration of a woman? Is he simply a fellow who’s a stickler for rules and regulations? We never know for sure. Of course, there are obvious markers.

Our best hint comes out of another man’s mouth as he reminds his daughter, “There’s right and there’s wrong and when you see the difference you’ve just got to speak up.” In Judge Thorn, McCrea has brought to life a man who holds to precisely those moral tenets.

He puts his safety in jeopardy, he makes himself unpopular and foregoes major payoffs that could help him live comfortably. All because his view of justice and of right and wrong are so lucid he sees no other way of going about his duties. Let there be more men in our world like the Judge. Not sticklers but men of immense integrity.

Stranger on Horseback is a testament to small-scale westerns that have the guts and the certain level of ingenuity to stand out and weather the ultimate test of time. Dig it out of obscurity, dust off the mothballs, and you might just find yourself in for a pleasant outing.

3.5/5 Stars

Cat People has one of those sensationalized B-picture premises and there are moments when its meager aspects let slip that this is a low-budget effort, but within those restrictions, it moves with a certain purpose and chilliness. It’s true that producer Val Lewton had a B-movie renaissance going on at RKO Studios and Cat People is one of his treasures.

Cat People has one of those sensationalized B-picture premises and there are moments when its meager aspects let slip that this is a low-budget effort, but within those restrictions, it moves with a certain purpose and chilliness. It’s true that producer Val Lewton had a B-movie renaissance going on at RKO Studios and Cat People is one of his treasures. At Oliver’s work, talk around the water cooler is made compelling in that his best pal and colleague is the sensible Alice (Jane Alexander) always ready to lend a listening ear. She’s genuine in accepting Irena for who she is because she can tell that Oliver earnestly loves her. But at the same time, she serves as a contrasting figure — someone who is completely different than this enigmatic creature.

At Oliver’s work, talk around the water cooler is made compelling in that his best pal and colleague is the sensible Alice (Jane Alexander) always ready to lend a listening ear. She’s genuine in accepting Irena for who she is because she can tell that Oliver earnestly loves her. But at the same time, she serves as a contrasting figure — someone who is completely different than this enigmatic creature.