Our introduction to The Mortal Storm feels rather flat. Bright and bland in more ways than one as we become accustomed to our main storyline. Professor Viktor Roth (Frank Morgan) is held in high regard all throughout the community as a prominent lecturer at the local university and beloved by his colleagues and family. The year is 1933 and the Bavarian Alps are still a merry and gay place to live. That’s our understanding early on as the Professor celebrates his 60th birthday with much fanfare and receives a commemorative memento from his class.

Our introduction to The Mortal Storm feels rather flat. Bright and bland in more ways than one as we become accustomed to our main storyline. Professor Viktor Roth (Frank Morgan) is held in high regard all throughout the community as a prominent lecturer at the local university and beloved by his colleagues and family. The year is 1933 and the Bavarian Alps are still a merry and gay place to live. That’s our understanding early on as the Professor celebrates his 60th birthday with much fanfare and receives a commemorative memento from his class.

In some ways, Frank Borzage’s picture shares a striking resemblance to All Quiet on the Western Front another film that makes its German roots blatantly obvious and yet it wears its incongruities like the ubiquitous use of the English language with ease. And as all the characters accept it, we do too as we begin to sink into the story. But crucial to this story is that they are not as accepting of other things. It feels a little like paradise. Life is good and people are happy. But we expect that at some point the time bomb will go off and it does. Adolf Hitler is elected Chancellor and just like that people begin to change. It’s a collective revolution — a youth movement of sorts.

Pastor, pacifist, and thinker Dietrich Bonhoeffer tore apart the Fuhrer concept straight away in a talk he gave in 1933, long before many of the later horrors during the Nazi reign of terror. But much as this film portrays, such an ideology only leads to destruction — a necessity to harm your brother. Bonhoeffer stated the following which feels surprisingly pertinent to this narrative:

“This Leader, deriving from the concentrated will of the people, now appears as longingly awaited by the people, the one who is to fulfill their capabilities and their potentialities. Thus the originally matter-of-fact idea of political authority has become the political, messianic concept of the Leader as we know it today. Into it there also streams all the religious thought of its adherents. Where the spirit of the people is a divine, metaphysical factor, the Leader who embodies this spirit has religious functions, and is the proper sense the messiah. With his appearance the fulfillment of the last hope has dawned. With the kingdom which he must bring with him the eternal kingdom has already drawn near…

“If he understands his function in any other way than as it is rooted in fact, if he does not continually tell his followers quite clearly of the limited nature of his task and of their own responsibility, if he allows himself to surrender to the wishes of his followers, who would always make him their idol—then the image of the Leader will pass over into the image of the mis-leader, and he will be acting in a criminal way not only towards those he leads, but also towards himself…”

And so it happens in this film. We see it around the professor’s dinner table first. Formerly, a forum for high-minded debate, it’s quickly become a battleground of ideology. Roth’s step-sons and most notably his daughter’s fiancee Fritz Marberg (Robert Young) have all been caught up in the rhetoric and promises of Herr Hitler. All other forms of thought and free thinking have been discarded, these new ideals burrowing into their minds, dictating their actions, and ultimately poisoning their lives and the lives of all those around them. I never thought it was possible to despise Robert Young but when his mind is polluted by an ideology as rancorous as Nazism it’s far from difficult.

We don’t see Jimmy Stewart until quite a ways into the film and he disappears from sight for some time following an escape to Austria from the Nazi clutches, but he’s still our hero imbued with that same iconic everymanness. He is the man to continue the open-minded, compassionate forms of thinking that Professor Roth exemplifies and subsequently get torn asunder.

Margaret Sullivan and Stewart yet again make a compelling pair following Lubitsch’s Shop Around the Corner. She is the good little German girl Freya who actually proves to have a backbone and he is the humble farm boy who stands by his ideals like Stewart always did. They are caught up in a love story amidst a world that seemingly lacks any shred of romantic passion.

Undoubtedly the Production Codes forbade from mentioning Jews in the story — the non-Aryans like Professor Roth, but that makes this film even more haunting, the fact that the people without a voice are not even acknowledged. They are silenced and remain silent.

With its overt portrayal of the Nazis as menacing thugs and brainwashed ideology machines, The Mortal Storm is startling. For years and years most all of us have read, heard, and seen a great deal on the Nazis that we have unknowingly compiled but this film brings many of those common factors to the fore. It’s obvious that people saw them then. They knew them then. They weren’t blind. Thus, it makes us beg the question what were other Europeans and Americans actually thinking? Because although The Mortal Storm might be the exception rather than the norm, there had to be a general consciousness about the Nazis.

Because the film hardly sugarcoats anything nor does it mince words. It’s surprisingly blunt and utterly bleak in its portrayal even with a bit of a bittersweet Hollywood ending. What’s left is a lingering impact that’s terribly affecting. Only at that point do we realize the total transformation the film world has gone through. Those opening moments of The Mortal Storm are so vital as it is only in the waning interludes where we truly comprehend how far things have fallen into hell.

It’s a stunning piece of work and this is not simply the ethereal love story I was expecting. It is a thoroughly gripping indictment of the Nazi menace and far more candid than I would have ever imagined. The Mortal Storm suggests perhaps most audaciously that there were people who waded against the pervasive current of the time. They let their lives be dictated by good will, decency, and personal relationships rather than any churning force of a single political ideology.

The final quotation pulled from the moving work of Minnie Louise Haskins “God Knows” ends like so:

“I said to a man who stood at the gate, give me a light that I may tread safely into the unknown. And he replied, go out into the darkness and put your hand into the hand of God. That shall be to you better than a light and safer than a known way.”

4.5/5 Stars

A quaint, unassuming film, especially up against other more lavish Ernst Lubitsch works like Trouble in Paradise and Heaven can Wait, Shop Around the Corner still manages to be in the upper crust of romantic comedies — even to this day.

A quaint, unassuming film, especially up against other more lavish Ernst Lubitsch works like Trouble in Paradise and Heaven can Wait, Shop Around the Corner still manages to be in the upper crust of romantic comedies — even to this day. Inherent in a film with this title, much like It’s a Wonderful Life, is the assumption that it is a generally joyous tale full of family, life, liberty, and the general pursuit of happiness. With both films you would be partially correct with such an unsolicited presumption, except for all those things to be true, there must be a counterpoint to that.

Inherent in a film with this title, much like It’s a Wonderful Life, is the assumption that it is a generally joyous tale full of family, life, liberty, and the general pursuit of happiness. With both films you would be partially correct with such an unsolicited presumption, except for all those things to be true, there must be a counterpoint to that.

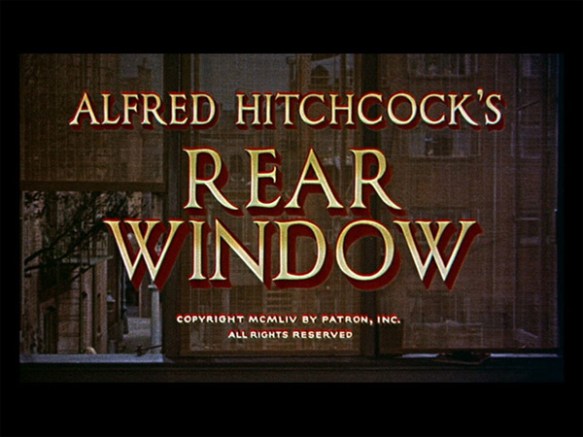

The interesting part is that as an audience we are fully involved in this story. We see much of the picture from Jefferies’ apartment, because there is no place to go, and so we stay inside the confines of the complex. In this way, Hitchcock creates a lot of Rear Window‘s plot out of actions occurring and then the reactions that follow. We are constantly being fed a scene and then immediately being shown the gaze of Jefferies. It effectively pulls us into this position of a peeping tom too. Danger keeps on creeping closer and closer as he discovers more and more. The narrative continues to progress methodically from day to night to the next day and the next evening.

The interesting part is that as an audience we are fully involved in this story. We see much of the picture from Jefferies’ apartment, because there is no place to go, and so we stay inside the confines of the complex. In this way, Hitchcock creates a lot of Rear Window‘s plot out of actions occurring and then the reactions that follow. We are constantly being fed a scene and then immediately being shown the gaze of Jefferies. It effectively pulls us into this position of a peeping tom too. Danger keeps on creeping closer and closer as he discovers more and more. The narrative continues to progress methodically from day to night to the next day and the next evening.