It occurs to me that the title Cesar et Rosalie is a rather peculiar choice for this movie. However, it’s also very pointed. If Jules et Jim was about two friends caught in a ceaselessly complicated love affair with one woman (Jeanne Moreau), then here is a story shifting the focus just slightly. This time it is Romy Schneider caught between two suitors.

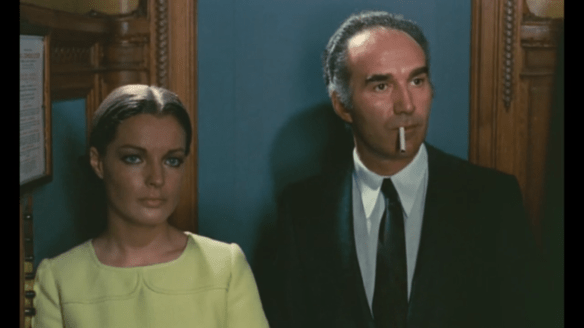

It opens with two men who both were coupled with the unseen woman named Rosalie. Formerly she was with a handsome comic book artist, but before they could ever get around to marriage (what would have been her second), she ended up with a middle-aged scrap metal man (Yves Montand). He’s quite successful in his trade while maintaining a penchant for gambling.

Whether it’s solely because they are represented by creative types, it feels like there’s a kind of vacuity about the younger generation. Yves Montand, now there is a man with something interesting about him. After doing some digging, I found out he was actually Italian by birth though thanks to his music and acting, he became synonymous with French cinema. Films like Wages of Fear and Le Cercle Rouge work in a pinch. He’s one of France’s indelible faces, and here he is another character with a lumbering larger-than-life posture.

Both a bit of an overgrown baby and a gregarious teddy bear. He can be found smoking his cigars and establishing himself as the life of the party. He loves to vocalize, and in contrast to his rivals, there’s something refreshing about his blustering style. You know what you’re getting.

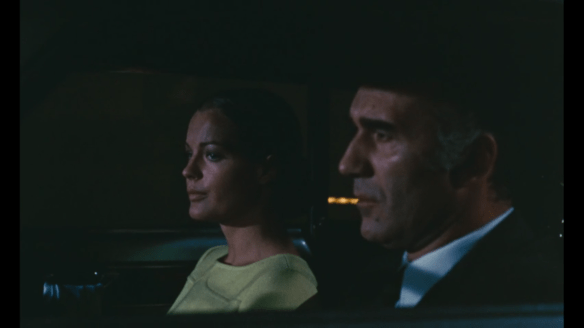

In comparison, I’m less inclined to be infatuated with any semblance of the bourgeoise milieu as embodied by David (Sami Frey). This might be a poor descriptor because he’s only a comic book artist, albeit a very successful one. But there’s a detached, casual air about him that feels far more refined. It lacks all of the volatile personality exhibited by Cesar. If I speak for myself, Cesar seems like one of the common men.

However, right about now it’s worthwhile to acknowledge a handful of his shortcomings. He’s quite petty and jealous for the affection of Rosalie. In one instance, his childish antics and brazen show of bravado leave them idling in the underbrush at the side of the road. In the aftermath of a convivial wedding party, a game of chicken ensues between him and David becoming a portent for future drama.

Although he and Rosalie have been together for some time, and they have a contentment between them, there is still this lingering sense of individuality. Rosalie is a mother. She has been married before and maintains her own independence. She remains with Cesar mostly because she wants to be, at least for now. That could easily change, and, eventually, it does. Her whims make her alight once more for David because his quiet charms have not atrophied with time. She feels the electricity between them still.

At the midpoint, the picture hits the skids. Cesar’s ugly underbelly comes alive as his transgressions and jealousy take over. He acts as if he owns Rosalie and in one harrowing scene practically throws her out the front door. He’s a wounded brute prone to violence. There’s no way to condone his behavior even as it reflects the toxic social mores of the era (or many eras).

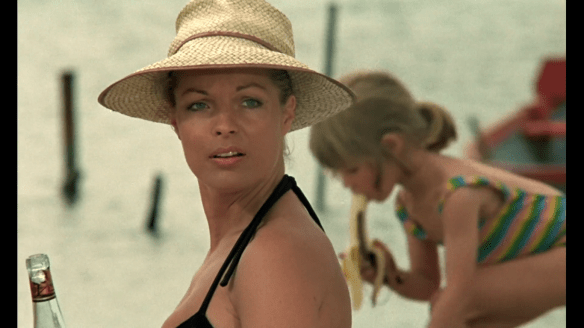

But of course, he can never forget her. He feels lost without her and so he resolves to find her with David. He tracks them out to their beach getaway but instead of coming to have it out once and for all, Cesar returns sheepishly with his tails between his legs. He’s paid for the damages he inflicted, and Rosalie looks over his sorry figure and can hardly contain her amusement.

It’s moments such as these where it becomes apparent how the movie is mostly able to coast on the goodwill of its stars and their various romantic dalliances. Initially, it feels like Romy Schneider spends a great deal of time in the kitchen grabbing drinks and making coffee for her man. However, she’s also a keen observer of male anthropology.

Like Moreau before her, she really does play the deciding part in this film. As much as it seems framed by the male perspective, though our title subjects have shifted slightly, Rosalie does hold a great deal of sway in the story. It does feel like these men need her more than she needs them or, at the very least, she is not willing to settle into this kind of relaxed equilibrium where they exist in a menage a trois without the intimacy.

Is it wrong to consider this the most French of romantic setups? It becomes plainly apparent that this is never just a film about Cesar and Rosalie. There must be parentheses or ampersand including David tacked on the end (or any other love interest for that matter). The film is far more crowded and complicated than a mere romance actuated by two solitary human beings with Sautet crowding the canvas and relational networks of the film with so many ancillary swatches of life.

Although it feels like it’s not about very much, Sautet is able to hone in on this core relationship and tease out both the comedic eccentricities found therein while still leaving us with this kind of wistful resolution. It’s not a tragedy in the same way Truffaut managed when he detonated Jules et Jim, but it leaves us with that sense of regret that love often conjures up in the human heart.

All these characters could have done things differently to patch things up, to stay together, and earn the Hollywoodesque ending. However, what leaves an impression is this kind of pensive anticlimax. It’s a lighter touch than The Things of Life or Max and The Junkman, even as it might owe something to Lubitsch.

3.5/5 Stars