Robert Bresson’s film is an extraordinary, melancholy tale of adolescence and as is his customs he tells his story with an assured, no-frills approach that is nevertheless deeply impactful.

Robert Bresson’s film is an extraordinary, melancholy tale of adolescence and as is his customs he tells his story with an assured, no-frills approach that is nevertheless deeply impactful.

There is one moment early on that sets the tone for the entire story to follow. Mouchette stands in her class as the line of young girls around her sing a song in harmony with one another. She is the only one not involved, standing sullenly as her headmistress passes behind her.

In front of the whole class, her face is dragged down to the piano keys and she is forced to sing aloud, her pitch nowhere near the mark. She goes back in line with tears in her eyes as the girls around laugh at her sheer pitifulness. But as an audience, it makes our hearts twinge with pain.

She is the girl who looks out of place at a carnival, her clothes frayed and clogs constantly clomping. She is the girl who doesn’t have enough money to pay for a ride apart from charity. She is the girl who gets hit by bumpers cars. She is the girl looking for a friend, but none can be found — the school girls having nothing to do with her and her father scolding her if she ever made eyes at a boy.

She is forced to be mother, housekeeper, and caretaker as her mother lies in bed deathly ill and her swaddled baby brother cries helplessly night and day. When her father comes home he’s of no use and when he’s out he’s quick to drink.

So in many ways, Mouchette understandably finds life unbearable. She never says that outrightly. In fact, I doubt a character in a Bresson film would say something like that because it wouldn’t feel real. It wouldn’t fit his MO. Still, every moment her head is tilted morosely or she trudges down a street corner dejectedly nothing else must be said. That’s why she slinks off into the surrounding forest and countryside to get away from all that weighs on her.

And even there she cannot find complete relief. One such night during an escapade she witnesses what looks to be a fight between two men from town who have feelings for the same woman. As they are drunk in the rocky depths of a stream, such a confrontation does not bode well. When both men go tumbling down and only one gets up, Mouchette believes she is privy to a murder. The perpetrator Arsene sees her and coalesces her to keep a lie for him, making sure she doesn’t say anything. But she’s also not safe in his presence and so she eventually flees into the night.

In the waning moments of the film, what we expected from the outset comes to fruition and Mouchette loses her mother, the only person who seemed to deeply care for her with reciprocated love. And as she wanders through town to retrieve milk for her brother, she turns off anyone and everyone who makes any pretense to help her. Of course, their help is always a backhanded or pious type of charity and in the same breath, Mouchette is not about to be thankful for them. It’s a self-perpetuating cycle of sorts. All parties are to blame.

In the end, she seems to be at her happiest rolling down the grassy hills away from any sort of human sorrow or interaction. It’s a sorry existence highlighted by very few silver linings. Bresson’s film hits deep with numerous bitter notes, offering up a life that is wounded and broken. Mouchette’s tragedy is great but perhaps the most important question to ask is where does her solace come from?

It’s interesting how Bresson often focuses on bodies in action, at times it almost feels like the characters are faceless. We know them, we see them but what they do and how they move speaks volumes about who they are. Posture, actions, desires, these are the things that define characters far more than even the words that cross their lips.

4/5 Stars

There’s something inherently striking about the title Mustang. It signifies something about the title girls, their free-spirits, billowing brown locks, continually running in a type of a herd, constantly full of life, movement, and motion. But with a mustang and any other creature full of life and vitality, there’s always an opposite force looking to impede, tame, and prod the spirit into some sort of submission. Because being free, being wild is constantly challenged in the world that we live in and this story is a prime example.

There’s something inherently striking about the title Mustang. It signifies something about the title girls, their free-spirits, billowing brown locks, continually running in a type of a herd, constantly full of life, movement, and motion. But with a mustang and any other creature full of life and vitality, there’s always an opposite force looking to impede, tame, and prod the spirit into some sort of submission. Because being free, being wild is constantly challenged in the world that we live in and this story is a prime example. “Nicole, you’re sleeping…”

“Nicole, you’re sleeping…”

The opening notes of Joan Jett hollering “Bad Reputation” made me grow wistfully nostalgic for Freaks & Geeks reruns. The hope budded that maybe 10 Things I Hate About You would be the same tour de force narrative brimming with the same type of candor. It is not. Not at all. But that’s okay. It has its own amount of charms that forgive the obvious chinks in the armor of this very loose adaptation.

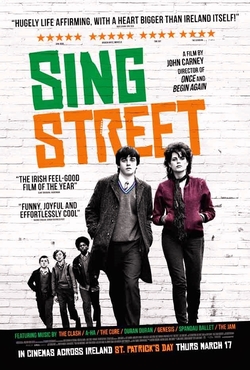

The opening notes of Joan Jett hollering “Bad Reputation” made me grow wistfully nostalgic for Freaks & Geeks reruns. The hope budded that maybe 10 Things I Hate About You would be the same tour de force narrative brimming with the same type of candor. It is not. Not at all. But that’s okay. It has its own amount of charms that forgive the obvious chinks in the armor of this very loose adaptation. A famed philosopher of the MTV age once sang “video killed the radio star,” and John Carney’s Sing Street is a tribute to that unequivocal truth. Certainly, it’s what some might call a return to form for the director, landing closer to his previous work in Once, and staging the way for some wonderfully organic musical numbers set against the backdrop of Dublin circa 1985. In this respect, it’s another highly personal entry, and Carney does well to grab hold of the coming-of-age narrative.

A famed philosopher of the MTV age once sang “video killed the radio star,” and John Carney’s Sing Street is a tribute to that unequivocal truth. Certainly, it’s what some might call a return to form for the director, landing closer to his previous work in Once, and staging the way for some wonderfully organic musical numbers set against the backdrop of Dublin circa 1985. In this respect, it’s another highly personal entry, and Carney does well to grab hold of the coming-of-age narrative.

It never feels flashy or superficial in these crucial moments. Any slick plot device or cinematic allusion falls away to get at the heart and soul of this film. It’s about coping with death and finding closure in that terrible event in life. Specifically for this one young man, but it is universally applicable to most every one of us. Especially when you’re young because as young, naive individuals, death can feel like such a foreign adversary. It’s so far removed from our sensibilities, and that’s what makes it so painfully unnatural when it strikes. In many ways, Greg is our surrogate. For all those who struggled to find themselves in high school, or college, or even life in general. And for all of those, who took risks on friendship in a world full of death and dying. Once more Me & Earl and the Dying Girl proved its worth, not by being a perfect film, but by being a heartfelt one.

It never feels flashy or superficial in these crucial moments. Any slick plot device or cinematic allusion falls away to get at the heart and soul of this film. It’s about coping with death and finding closure in that terrible event in life. Specifically for this one young man, but it is universally applicable to most every one of us. Especially when you’re young because as young, naive individuals, death can feel like such a foreign adversary. It’s so far removed from our sensibilities, and that’s what makes it so painfully unnatural when it strikes. In many ways, Greg is our surrogate. For all those who struggled to find themselves in high school, or college, or even life in general. And for all of those, who took risks on friendship in a world full of death and dying. Once more Me & Earl and the Dying Girl proved its worth, not by being a perfect film, but by being a heartfelt one.