What Delmer Daves has gathered together is an oddly compelling mix of rural drama with undertones of horror somehow merged into what we might be able to pass off as a strain of noir. What I find particularly intriguing is not so much the mysterious Red House at the core of the story, as the impending pandora’s box of doom and personal revelation, but it’s the curious character dynamics that stay with me.

Edward G. Robinson stars as Pete, a man with a wooden leg who has long lived in seclusion with his sister and adopted daughter. He’s been content with this lifestyle remaining self-sufficient and living off the bounty of their farm. He hasn’t needed anyone else for a long time and he’d generally like to keep it that way.

Perhaps by this point, I simply take his skill for granted but it was the performances around Robinson that were the most engaging for me. Judith Anderson plays a surprisingly compassionate and maternal woman who has sacrificed a lot and is more sympathetic than most roles I can recall within her body of work.

But this is a young person’s story as much as it’s about the adults. That’s where much of the heart lies. The local high schoolers ride to and from school on the bus and in the back row is where the story’s main romantic relationship of interest is conceived in one of the most visually awkward setups imaginable. We meet a young man with his girlfriend with another girl sitting in the frame uncomfortably.

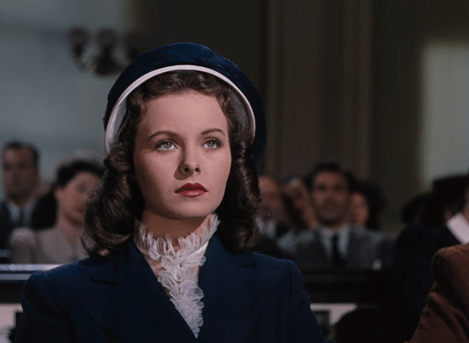

Lon Mcallister returns with the same bright and boyish countenance from Stage Door Canteen bringing a kindly spirit to the screen that’s wholly unassuming and morally upright. Likewise, Allene Roberts proves reminiscent of the demure Cathy O’Donnell while her eyes are imbued with a near doleful innocence. She is the girl who sits on the bus, the awkward third wheel. As Nath and Meg, they are two young folks exuding an utterly sincere candor.

Meg earnestly wants the young man to help her uncle out on his farm. She thinks he will be of great help and she excitedly goes to her aunt to share the good news that he’s accepted the offer. It’s even more curious that Nath so quickly accepts the job offer knowing it will mean long hours, a mile walk out of his way, and time spent in close proximity to this earnest young girl.

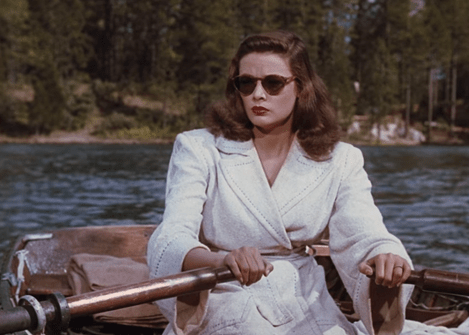

Because they aren’t a couple. This privilege goes to Julie London as his sultry and slightly entitled beau Tibby. Think about it too long and they don’t seem to fit each other but since it is already, we buy into it; she might just like a nice guy like him. Because in this slice of America, the boy-next-door speaks to something desirable still.

However, there’s also Rory Calhoun as Teller, the dark and imposing stud who Pete has made the keeper of the forests near his farmhouse for some undisclosed reason. That in itself is a strange setup but if anything it gives the dashing man free license to lord over the mysterious territory and keep others off the woodlands by any means possible. He’s been sanctioned by Pete to undertake any measures necessary and he does.

Just as we have two kind, innocent people to lend an underlying decency to our picture, we have their foils in two beautiful people who look to be out for themselves. Surely, they must get together and such a scene is instigated when the broodingly handsome fellow waits to intercept Tibby on her way home. He carries her across a stream and snatches a kiss from her as due payment. She doesn’t seem to mind too much.

But that is hardly the calamitous heart and soul of the picture, the dark underbelly of Middle America hidden away in isolation. For that, we must look to Robinson harboring a secret bubbling ominously beneath the surface. His niece is intent on finally visiting the house that he has continually forbidden her to see. She wants to know why. She has the right to know even if it hurts her.

But again, I never cared too much about the deep dark secret buried there because I think most of us have a general inclination of what it might be about. The anticipation comes in the created experience, not the forthcoming outcomes.

In some regards, The Red House shares some commonalities with the noirish western thriller Pursued, also released in 1947. Aside from featuring Judith Anderson, the other picture also concerned itself with psychological issues and a murky past laden with all sorts of trauma. But The Red House is more straightforward and clear-cut making the interpersonal relationships between characters paramount over any sequence of action.

The narrative is capped with a picturesque final shot worthy of such a peculiar movie. Framed with its idyllic beginnings and equally peaceful panoramic endings, it’s nearly possible to forget what we’ve just seen. All the rough edges have been smoothed out and the dark recesses of rancor replaced with young love.

It’s this startling dichotomy that gives the film’s its allure; that and the strength of its performances. Everyone plays their types exquisitely from the established stars like Robinson and Anderson to the winsome newcomers. Allene Roberts left a striking impression most of all. To read about her life story is to fall in love with her even more. She seems like a lovely person. God bless her.

3.5/5 Stars

Note: Since originally writing this review, Allene Roberts passed away on May 9th, 2019.