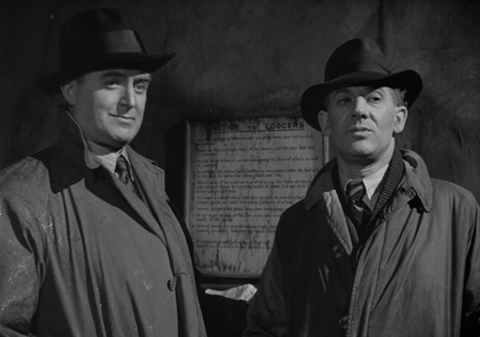

Gregory Peck’s pleasantly resonant voice brings us into the moment. The scene is unimaginative yet unmistakable with its obviously scaled-down establishing shot. Pittsburgh. Smokestacks and steel. These are the days of Andrew Carnegie and the transcontinental railroad wrapping its way east to west, making mythical magnates out of mortal men.

Valley of Decision is about this same monumental national narrative albeit stripped down to a microcosm meant to be far more intimate. In a manner of speaking, it succeeds by first setting our sights on a group of Irish immigrants. They are stereotypically spirited with a brogue to match.

Mary Rafferty (Greer Garson) makes her way home through the humble neighborhood she calls home to announce the latest piece of news. Amidst tough times, she has found herself a decent wage! The only complication is that she’ll be serving as maid to the Scott family, owners of the town’s local mill. Although Mary’s not a girl to turn down a job, her curmudgeon father (Lionel Barrymore) has maintained a lifelong grudge against Mr. Scott, seeing as it was the factory that lost him the use of his legs. He’s never forgiven them even with the recompense they’ve provided.

This is an instant source of conflict although it’s initially unrealized. Because given how they are built up, it’s rather surprising how everyone in the Scott household seems generally benevolent, if not a bit stuffy.

Mary arrives and we’re curious to know her place. We get our first look at Gregory Peck. He sneaks up the stairs to be rushed by his affectionate siblings. His mother (Gladys Cooper) follows in all civility. Each moment is taken in by the new help, perched in the drawing-room with each reaction made blatantly obvious. This is her first impression as well as ours and she beams ear to ear.

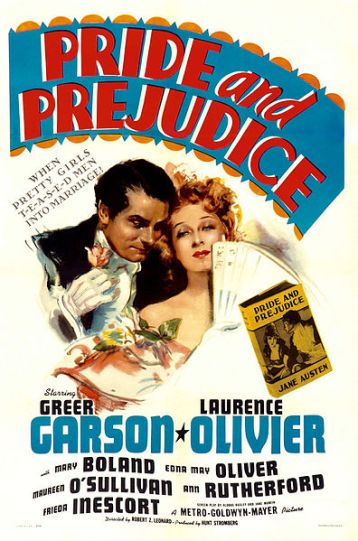

Garson’s character girds a spellbinding wit of the Irish about her, settling into her new occupation for the Scott family quite seamlessly and casting off her early nerves. Between the dishes and the spoiled children, she handles it with disarming aplomb and a certain bright-eyed reverence as only Greer Garson can supply.

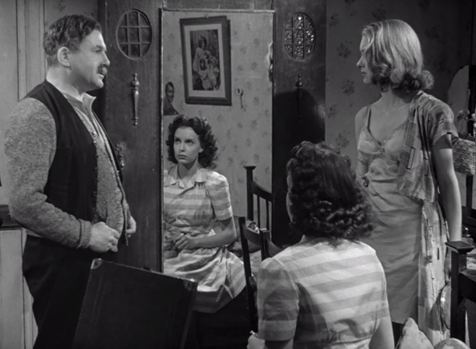

If it’s not obvious already, Valley of Decision is a social drama with characters tied closely together. There’s the sectioning off of social spheres between the affluent and their more humble help. Then, you have the meeting of the men over cigars and business as the women busy themselves with frivolities. Curtains, for instance.

Tiptoeing through all these spaces like a fly on the wall is Mary Rafferty. Certainly, her place in this world is obvious, and yet she is accorded a very unique role walking through the parlors and dining rooms of the elite — privy to their conversations and activities — and an integral part of every part of her lives. No matter her family background.

It’s no secret a burgeoning romance starts in on her innocently enough. She’s a fine and glowing conversationalist. He’s charming and handsome. How could they not get together? But she dutifully understands her place. It wouldn’t be proper and with no prompting, she makes her way across the Atlantic in service of Ms. Connie (Marsha Hunt), effectively increasing the space between them. The mistress of the manor understands her predicament and privately pities her.

Then, one day there is a strike at the factories. Again, it’s no shocking epiphany. Anger and discontent are churned up and the bullish pride of Mr. Scott (Donald Crisp) and the sense of license for better wages by the unionizer Jim Brennon, looks to be at an impasse.

The true “valley of decision” (an allusion to the Old Testament’s admonition from Joel) is when all the events come to an inevitable head. A fragile peace can be maintained no longer, and all sides suffer calamitous devastation. Because the consequences are great when the Scotts and their opposition come face to face to have it out for good. Not even Mary nor her relinquished lover can make it right again.

Whether torn from the pages of the book or dreamed up by the screenwriter, Valley of Decision is very much a stilted melodrama with all sorts of manipulative twists coming at us with such continued force, it gets to be wearisome. It never ends.

The narrative flits so undecidedly between the warm chemistry of the leads and this overly theatrical landscape played out against the family’s steel mills. You might blend How Green is My Valley, King’s Row, Giant, Home for the Hill, and other analogous films, but somehow Valley of Decision still comes out the weakest of the brood. It cannot seem to reconcile its main conceit to a satisfying end.

It’s assembled with all the trimmings people might easily turn their noses up at when considering Hollywood movies of old. It boasts sentiment and courts melodrama. There’s the aforementioned voiceover to set the stage and stirring crescendos of mighty music in love and in tragedy. Characters can easily be pigeon-holed by their types all the way down to a spoiled Marsha Hunt, the insufferable childhood sweetheart played to a tee by Jessica Tandy, and Dan Duryea, not quite having found his more suitable niche as a noir baddie.

There’s also the underpinnings of Mary courting on the side of the wealthy and well-to-do. She sympathizes with them, making them seem like the victims of a system more so than the destitute bottom dwellers. I’m not sure what to do with this.

Because it’s true Mr. and Mrs. Scott are a most benevolent pair, and we grow to love them. Crotchety Lionel Barrymore, sulking in his wheelchair, doesn’t do much for the P.A. of the common man, but nonetheless, it’s a startling turn.

Taken as these disparate pieces placed together, the movie is an uneven compilation, all but borne on the shoulders of Greer Garson and Gregory Peck, who by any cursory glance, seem ill-suited as romantic partners. At the very least, they’re disparate figures.

She was a mature star, finally coming into her own as one of the prominent performers from the U.K. now making it big in Hollywood. He was an up-and-coming stage actor with the formidable build and roots in La Jolla California then Cal. Yet they share an amicable spirit somehow allowing them to fit together due to their mere ability to counter one another’s playful ebullience.

It does feel like a remarkable crossroads in careers. Garson was beloved, but would never regain her major box office with the dawning of the 50s and new tastes (even with a resurgence of success in the 60s). Gregory Peck was just beginning. One wonders what Greer thought of Roman Holiday and To Kill a Mockingbird? It’s easy enough to believe she would have liked them.

3/5 Stars