“When you’re 16, they call it sweet 16. When you’re 18, you get to drink, vote, and see dirty movies. What the hell do you get to do when you’re 19?”

“When you’re 16, they call it sweet 16. When you’re 18, you get to drink, vote, and see dirty movies. What the hell do you get to do when you’re 19?”

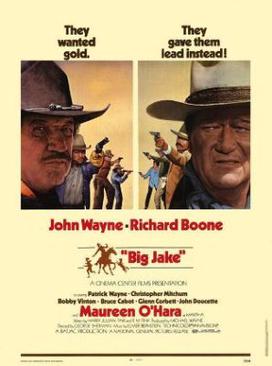

Oftentimes sports films are memorable for merely pioneering underdog stories or analogous themes meant to inspire. But then we get a whole slew of imitators coming afterward. You see it with baseball, basketball, football — most of the big ones — each one already boasting a substantial fanbase and accepted canon of classics. However, cycling has never been as popular in the States and thus, watching Breaking Away, even today, feels like it’s own unique experience.

Sure, it’s the age-old, small-town coming-of-age story. There are too many of those to even begin counting the good ones (much less the bad). We’re supposed to care for four dreamy highschoolers going out against the world. There is so much that could feel hackneyed and overdone. But married with cycling, Breaking Away has yet to meet its equal. Off the top of my head, there is no other cycling film that channels this same sense of exuberance or captures a certain time or place like the Bloomington, Indiana featured herein.

Because along with Hoosiers, Breaking Away is in the running for the most Indiana movie of all time. It lives and breathes the tangible air made very apparent in Steve Tesich’s script. He has an intimate understanding of this area, having lived there in college and even having been a member of a cycling team.

So for every forgettable yarn that I’ll graciously refrain from mentioning, we get an American Graffiti or Dazed and Confused. Breaking Away is very much the same. Their skill comes in taking the individual and the deeply personal memories, only to realize them in a way that cannot help but be universal.

It grabs hold of those strains and feelings that we all can relate to, no matter our background or race or creed. In some circles, it has to be the greatest common denominators. Like not knowing what you’re doing with your life. Having a difficult relationship with parents. Even being the underdog forced to prove yourself against Goliath.

In this case, our protagonist is a scrawny kid (Dennis Christopher), nevertheless, obsessed with cycling and therefore, Italian culture. He’s going through a phase that’s just about driving his father up the wall. He’s a man who won’t have any “inis” in his house from Fellini to Zucchini.

Dave’s a cultural sponge where imitation is and always will be the highest form of flattery, even going so far as to thank the saints on one particularly fortuitous occasion (“Oh Dave, try not to go Catholic on us”). Along with the constant biking comes the Italian language used in the home, opera records, and shaving his legs (like an Italian).

It’s how he’s able to make a unique identity for himself aside from being the former sick kid who doesn’t know what he’s doing with his life. We’ve all been there. At least he’s added a little flair to his existence while he still can.

What ensues is a cringe-worthy romantic introduction as he submerges into his Italian persona just to get acquainted with a girl. It’s almost a defense mechanism because he’s too unsure to be himself; it’s much easier to put on a larger-than-life, sing-song facade. If it gets rejected there’s no harm. Moonlight serenades outside the sorority house window follow and stirring heart-to-hearts.

If Italian culture and a girl become his main extracurriculars, then most of his formative time is spent in the company of his buddies. Mike (Dennis Quaid) is the tough guy with the chip on his shoulder. He’s protective of his turf and always ready to rumble with the more affluent sects of society. He’s not about to back down from anyone.

If there’s a Mike in every crowd, there must also be a lovable airhead like Cyril (Daniel Stern), good for a few laughs so tensions simmer down. The last amigo is the shaggy-haired and affable pipsqueak Moocher, who is no doubt in the most serious relationship of all the boys. In his own way, he might actually be the most mature.

Regardless, they are constantly reminded of the realities of living in a college town. Part of this is the socio-economic aspect. They spend their summers swimming in the local quarries, as opposed to the sleek indoor swimming pools and co-ed decadence of all the out-of-town college kids.

They proudly wear their somewhat derogatory label as “Cutters,” the local blue-collar families who either don’t have enough money to get into the school or perhaps they aren’t bright enough. I’d be willing to believe the former more than the latter.

However, if Dave Stoller thinks he’s found who he is, events cause him to reevaluate his very identity. Not about being a cyclist — he still can ride faster than just about anybody in town — but there’s more to him than that. He’s forced to sort it out.

Because the day he’s been waiting for finally arrives, and he realizes his dream to ride with the team from Italy who have come to Indianapolis. Being in their stead provides him with a rude awakening. When he gets sent careening off the tracks by some foul play, his idols tumble right down with them. He realizes the necessity of being his own man and so he goes out on another limb.

He admits to the girl his whole Italian shtick was an act. He made it all up. Not surprisingly, she lashes out in bitterness over his bout of deception. It sends everything spinning into a tizzy. The untouchable, alluring college girl has a moment of genuine frailty and our hero is ousted for what he was — not simply an insecure adolescent — but a jerk for putting her on.

There is also tangentially the obvious paralyzing fear of stepping off into the great unknown that is the future and out of his father’s life into his own. What Breaking Away does a fine job at is coloring the relationships, not just between peers but a father, son, and mother.

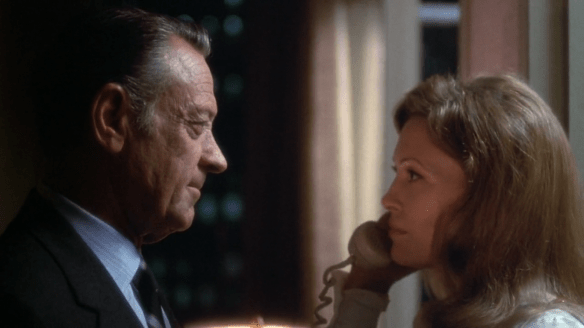

Barbara Barrie is sublime as a steady ever-understanding wife and calming maternal figure. She performs the role seamlessly. Equally important is Paul Dooley as Ray Stoller. He’s full of irritations and hilarious punchlines that give way to real feeling.

He’s born out of a generation that does not know what affection is. They are proud and they work hard and grit it out. He helped excavate the land that became the university, and now he’s a used car dealer. Looking at his son he sees someone who is soft and inexperienced. And yet when he’s really honest and speaks his heart, he wants something better for his boy than what he had.

This is how you know parents care. No matter how much they might grumble and gripe, most everything they do is to set up their children for a better future. It’s no different in Breaking Away. Coincidentally, parents almost always make the greatest cheerleaders because they’re always there.

If Dave’s tumble off the bike and the renunciation of his girlfriend were subsequent slaps in the face to his ego, then the Little 500 Race is the obvious chance at redemption. Again, the beats are oh-so-familiar but at this point, it doesn’t matter. The wheels are spinning and we’re ready to cheer on the boys as they seemingly take on the world or at least all the hotshot fraternities dismissing their very existence. It’s superfluous to mention the ending.

The euphoric joys of a goosebump-filled finale cannot be totally dismissed. It makes one realize the power of characters that we are able to empathize with. Knowing what will happen doesn’t take away one ounce of the excitement because we feel for them and are urging them to succeed.

We are a part of the Cutters team and every burn, every lap, every push they make against adversity, means something to us too. There is nothing self-important about it and this above all else allows it to be a sheer delight.

Peter Yates career, while somewhat uneven, boasts some quality outings if you consider the likes of Bullitt and Breaking Away. They could not be more different (the settings alone are starkly juxtaposed) and yet they do capture a very specific milieu — in this case, through a free-and-easy coolness — with kinetic energy utilized to its utmost degree.

Both are a reminder that far from taking away from the human experience — vehicles can be an extension of them, in allowing characters to realize greater potential. Bullitt in his charger, bouncing through the streets of San Francisco and then Dave blazing down the highways and byways on his bike in and around Bloomington.

The evocation of a specific place with corresponding feelings is so important. Content doesn’t matter as much as long as it manages to leave a lasting impression on us. Evocative narratives do just that.

4/5 Stars

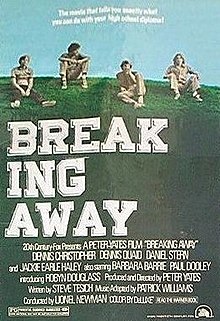

“That’s the thing about secrets. We all know stuff about each other; we just don’t know the same stuff.”

“That’s the thing about secrets. We all know stuff about each other; we just don’t know the same stuff.”

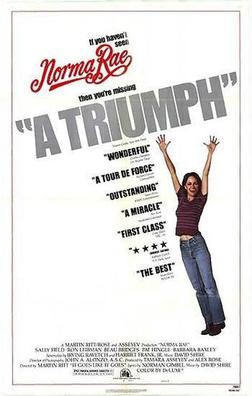

If you had any trouble possibly liking Sally Field before — consequently, one of the sweetest actresses ever to cross the screen — then there’s little gripe to be had with her any longer. Norma Rae really does feel like a gift for her. Both as a story to be a part of and a character to portray since both speak to us intuitively as an audience.

If you had any trouble possibly liking Sally Field before — consequently, one of the sweetest actresses ever to cross the screen — then there’s little gripe to be had with her any longer. Norma Rae really does feel like a gift for her. Both as a story to be a part of and a character to portray since both speak to us intuitively as an audience.