Any chance I get to champion Ivan Dixon, I do my best because he’s such a groundbreaking individual who rarely gets the credit he’s due. Ostensibly, he’s known for playing Kinch on Hogan’s Heroes, a part that was pioneering and ahead of its time, if mostly a thankless role. I love him dearly as an old friend, but I never begrudge him not playing the supporting role in the 6th and final season of the show.

Any chance I get to champion Ivan Dixon, I do my best because he’s such a groundbreaking individual who rarely gets the credit he’s due. Ostensibly, he’s known for playing Kinch on Hogan’s Heroes, a part that was pioneering and ahead of its time, if mostly a thankless role. I love him dearly as an old friend, but I never begrudge him not playing the supporting role in the 6th and final season of the show.

Because Dixon had roots in a rich tradition of stage and film he came by honestly from his formative years in the cultural hub of Harlem.

His early film career is littered with interesting parts including Raisin in The Sun, Too Late Blues, and Patch of Blue. However, his finest hour, showing what he was truly capable of given the right opportunity came in Nothing But a Man, a criminally underseen film with Abbey Lincoln. It feels like an unsung masterpiece of the 1960s.

Although he was never allowed to reach the superstardom heights of Sidney Poitier in the film industry, Dixon was a compelling, intelligent actor in his own right and given the dearth of great roles for black actors, he parlayed his occupation into a career as a director behind the camera.

Beyond showing up in a cult classic like Michael Schultz’s Car Wash, he directed more than a handful of episodes of The Rockford Files and numerous other high profile programs of the ’70s and ’80s, The Waltons and Magnum P.I. among them.

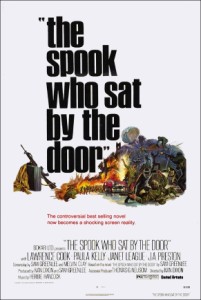

The Spook Who Sat by The Door might have budgetary constraints and, therefore, simple means, but it stands as one of his most visceral achievements behind the camera, especially when he was given worthwhile material.

The film was adapted from Sam Greenlee’s novel of the same name about a man who climbs the ranks of a CIA training regimen as a token black man only to utilize his espionage skills to empower grassroots black power movements in his community.

In this way it plays as a startling and satirical subversion of clandestine counterintelligence activities of the 1970s found in the contemporary moment. It has the packaging of an exploitation film and yet the writer, director, and actors are primarily black. They give the picture a different point of view that runs against the grain and feels ripe for rediscovery by willing aficionados in the 21st century. Because its depictions feel almost like the antithesis of a traditional, innocuous potboiler.

The opening scene in a Senator’s office is a barometer for the rest of the movie; this tone deaf civil servant looks at possible ways to gain the negro vote (after an ill-advised speech on law and order) so he shifts blame to the CIA.

There’s a complete dearth of Black agents within the organization. They respond rapidly to rectify the situation and add some token minorities to their ranks. If it’s not evident already, the satire is blatant and all the white characters feels like wonderfully buffoonish marks.

Dan Freeman (Lawrence Cook) is an exemplary candidate if a bit standoffish. He also becomes the last one standing among his peers. Even if he’s called an Uncle Tom, he knows the primary way to get ahead is to play the white man’s game…

He’s highly-educated, courts a beautiful girl (Janet League), and has the kind of model life broader society extols. Except it might all be a charade because he has far more sinister intentions.

Under the banner of law and order, he runs a parallel operation. He commandeers a radio station to preach his message of revolt against the city, and they’ve taken on guerilla tactics. As part of their righteous war they take over local military arsenals cloaked by night and create a cell of revolution to do battle with the establishment. They bide their time and build up their chain of command reminiscent of The Battle of Algiers.

One of the statement moments involves Dan’s associates capturing their primary adversary, neutralizing him, and leaving him as a black sambo in tar, strung-out on acid and left for dead. It’s such a jarring image one doesn’t soon forget by repurposing black stereotypes in a new perturbing context.

Jules Dassin’s Uptight feels more thematically rich in the wake of Dr. King’s death while pushing the boundaries of reality, but The Spook Who Sat by The Door presages something like Do The Right Thing. It captures the turmoil of the cultural moments like Watts or the Democratic National Convention with a visceral immediacy. It feels like the images could be ripped from the headlines as we watch the world quake and seethe with rage. It’s hard not to feel queasy.

You can easily understand how why the establishment would want to bury a film like this. Now it feels prescient, even dangerous, poking and prodding our nation’s fault lines with a gleefully stark abandon.

While I’m more easily attuned to more sincere cinema — Nothing But a Man is a good example — it’s difficult not to commend Dixon and company for their steely-eyed vision. Because The Spook Who Sat by The Door feels like an uncompromising, unfettered work that shocks us out of our day to day status quo.

Sometimes when people won’t listen or can’t hear, it doesn’t help to whisper politely. You need a resounding gong to shock them out of their reverie. It stings but then that seems like a small price to pay for a fraught history, especially if it leads to some kind of change. The most horrifying reality is a preconceived future where nothing changes…

Sadly, Ivan Dixon didn’t get many more good opportunities to showcase his directorial talents in film. It says more about the industry than anything else. But for the rest of us, his career is filled with work reflecting a persistently compelling actor-director. He made the most out of what he was given with an impressive career. It’s a shame he wasn’t given more, but that makes a film like this all the more important.

3.5/5 Stars

The cultural event the whole world seems to have been waiting for has finally arrived. Avengers Endgame is finally open to the public. The secrecy can cease. The debates can begin. Disney can start raking in the billions. And I presume, on the whole, the general public can let out a collective sigh of relief. The studio hasn’t ruined the tightly shepherded franchise and for those with a share of skepticism, Avengers‘s “final chapter” does some things quite well. At the very least, it brings back the epics of old for one evening of entertainment. That in itself is enough of a compliment.

The cultural event the whole world seems to have been waiting for has finally arrived. Avengers Endgame is finally open to the public. The secrecy can cease. The debates can begin. Disney can start raking in the billions. And I presume, on the whole, the general public can let out a collective sigh of relief. The studio hasn’t ruined the tightly shepherded franchise and for those with a share of skepticism, Avengers‘s “final chapter” does some things quite well. At the very least, it brings back the epics of old for one evening of entertainment. That in itself is enough of a compliment.