If we had to provide a broad sense of Cheyenne Autumn, it would be all about the mass Exodus of the Cheyenne in 1878 as they journey from the arid land they’ve been subjugated to back to the land the white man had promised to return to them all along.

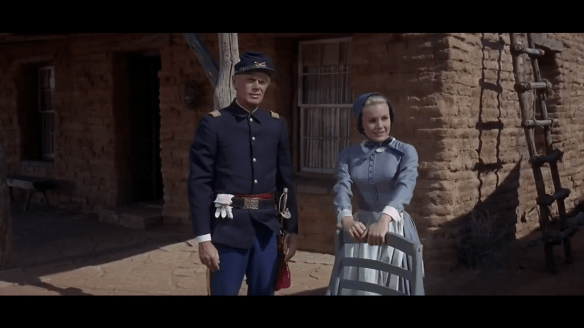

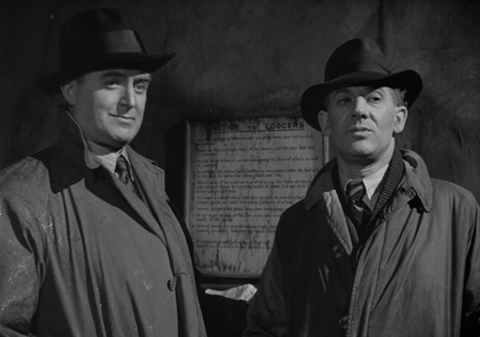

This is a Hollywood rendition so, obviously, it’s not expected to stick strictly to facts nor does it. The extras John Ford used throughout the picture were in fact Navajo, who spoke their native tongue. He also loaded up on a Hollywood cast headlined by Richard Widmark returning after Two Road Together, portraying an officer in the U.S. Army, Captain Thomas Archer, far more disillusioned in his post than his predecessor.

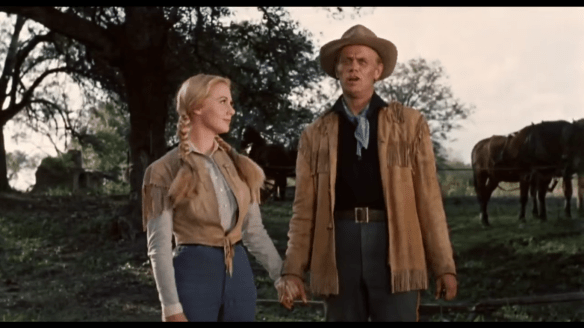

In the film’s opening grand gesture, the Cheyenne make the long trek hours early, in preparation for their meeting with the white man — a meeting that was supposed to come through on a wealth of promises. Everyone is there waiting anxiously at the military encampment. Among them, Deborah Wright (Carroll Baker) and her uncle have made it their life’s work to minister to the Native Americans as suggested by their benevolent Quaker faith.

The only people who don’t show up are the big wigs from Washington, offering yet another rejection and another sign of disrespect. As they leave the encampment, empty-handed once again, there’s in a sense of unease about it. Though the pompous blaggards back east have no concept of their egregious blunder, there’s no question reckoning will come in some form.

This is made apparent and for once in a Ford picture, beyond simply casting a sympathetic eye, the director finally seems to be acknowledging the grievances against the American Indians. Because they have to face arrogant, deceitful men who fatuously believe they have a right to everything they touch. They have no respect for the land, only what they can acquire from it. Soldiers who are supposed to be peacekeepers, as well as tacticians, are equally suspect.

In a fine bit of casting, Patrick Wayne plays a young upstart who has waited his whole life to have it out with the Cheyenne, and the circumstances make no difference to him, even if he has to create them himself. Other soldiers like Karl Malden’s commander espouse unprejudiced mentalities only to be frozen by the chain of command. It proves equally inimical, if not more so.

Under Archer’s command are also numerous steady, career soldiers like Mike Mazurki, Ben Johnson and Harry Carey Jr. To have the latter two in yet another Ford picture is certainly a fitting remembrance. They were as crucial to his work as any of the larger stars like John Wayne or James Stewart (more of him later).

Wagon Master and Rio Grande, from 1950, would be enough for many actors to build a reputation on. Even over a decade later, it’s a testament to this close-knit bunch that they still remained steadfast to the end. These are when the sentimentalities of the picture are most apparent.

In all candor, Cheyenne Autumn is long, at times arduous, but within that runtime, it speaks to so much, including Ford’s own legacy. This is what makes it such a fascinating final marker in his career. Again, it’s the side of the western movie he never truly showed before. It’s as if age has softened him to what he did not see before.

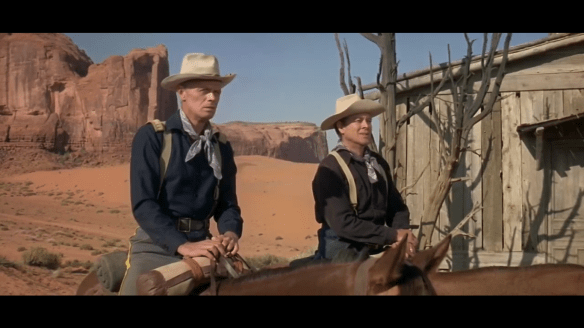

We’re in Monument Valley on the eve of a skirmish. We’ve seen this scene before but from the other side. Native Americans digging in to fight the cavalry on the other side of the canyon. This is not a battle between the heroes and villains but the victors and the victimized.

Whatever flaws come to the fore with a white director making a movie about Native Americans, so be it. They are present, but none of this can totally discount the interludes of natural beauty and deep affecting sympathy on display.

Initially, Ford had wanted to cast some version of Anthony Quinn, Richard Boone, or Woody Strode in the roles of the Indian chiefs. All men consequently had some Native American heritage. The parts of Little Wolf and Dull Knife ultimately were given to Mexican-American actors Ricardo Montalban and Gilbert Roland. The addition of Dolores Del Rio and a wordless Sal Mineo also feel equally peculiar. Mind you, these are only caveats mentioned in passing.

Cheyenne Autumn feels like a glorious mess of a film. It’s as epic as they come and striking for all its splendor; it’s also all over the place in terms of narrative. Perhaps Ford’s not totally invested here. This was never his main concern nor his forte. And in his final western, he does us a service by coming through with what he does best.

What else can we mention now but Monument Valley — the locale most closely identified with him — and yet it could just as easily be turned around and commended as the place he most identified with. Again, we can almost speak in parables because it can represent so many things from beauty to ruggedness from life and then death.

Take, for instance, when the chief elder is finally laid to rest, and the rocks are dislodged to form his burial chambers — off in the distance more of his people ride across the plateaus — it says everything that needs to be said. It is a moment of closure on all the images Ford himself ever captured in his home away from home.

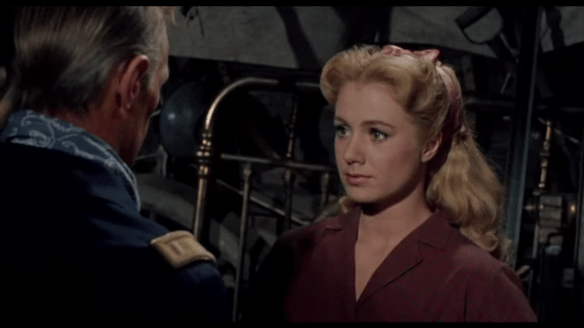

As a short respite, John Ford provides a highly comedic Dodge City intermission with Jimmy Stewart, Arthur Kennedy, and John Carradine among others. You’ve never seen Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday quite this jocular as they play poker, ride around in a buggy, and help rescue a floozie (Elizabeth Allen) running around with a parasol and a ripped dress.

Now it doesn’t make a whole lot of sense. It would be easy to cry foul for mixing disparate tones and totally flipping the script of the movie. This isn’t wrong, but it doesn’t fully take into account Ford’s intentions. He knows full well what he is doing, using the language of the moviegoing public bred on the epic. It injects brief levity into an otherwise dour picture. In fact, it might be too much levity, although it could make a fine comic western all its own.

Because I won’t pretend the drama doesn’t wear on. The beginning is far more compelling than the end, but the journey is of paramount importance and what it represents. Although Edward G. Robinson plays one voice of reason back east and Widmark plays another enlightened savior out in the field, not to mention Baker’s tireless quaker acting as a protector of the Cheyenne children, they are not all-powerful.

It’s as much a story of loss and failure as it is of tragedy and miscommunication. Again, this is not to say any of this is to be taken as truth and lines drawn in the sand when it comes to what the history books say. But Ford is working the only way he knows how, with the strokes of a painter on this canvas illuminating a story. He is making amends in an imperfect, fragile way. Do with it what you will.

While it’s not the glorious heights one might have guessed for John Ford’s final picture in Monument Valley and his final western, somehow it feels like a fitting capstone just the same. The tone says as much as anything else in the picture. It’s yet another elegy reminiscent of She Wore a Yellow Ribbon and many of his earlier works. Except this would be the last one. It was the autumn of his career as well.

3.5/5 Stars