Only Billy Wilder would dare to make such a film. Somewhere amidst the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre and men dressed in drag, he could find the inspiration for one of the most high-powered, zaniest, even subversive comedies of all times. There’s very little overstatement in that assertion because Some Like it Hot is all that and most importantly it’s just good unadulterated fun.

Only Billy Wilder would dare to make such a film. Somewhere amidst the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre and men dressed in drag, he could find the inspiration for one of the most high-powered, zaniest, even subversive comedies of all times. There’s very little overstatement in that assertion because Some Like it Hot is all that and most importantly it’s just good unadulterated fun.

It finds its genesis in the Jazz Age of Chicago circa 1929 where gangsters like Spats Colombo (George Raft) are running the streets, the crash hasn’t quite hit yet, and the Dodgers are a long way away from leaving Brooklyn. George Raft takes on a parody role hearkening back to the days of Scarface, but this time, there are a lot of laughs in the wake of his destruction.

Small-time musicians, Joe and Jerry, are living paycheck to paycheck and things aren’t going so hot for them when the authorities raid a not so legitimate establishment. Immediately they high tail it, but they’re not safe for long when they unwittingly stumble upon the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. They frantically flee the scene of the crime knowing the mobsters will soon be after them and to make matters worse they have no money. What to do? What any desperate pair of musicians would do, dress up as women and join an all-girl ensemble for three glorious weeks in sunny Florida. Sounds ludicrous when Jerry (Jack Lemmon) first drops the idea half-serious, but after the hot water they find themselves in, Jerry (Tony Curtis) takes him up on the masquerade.

So they pack their bags, do up their faces, and change their voices an octave or so higher. They wobble to the train station on top of their heels as Josephine and Daphne, just what the band leader Sweet Sue ordered and our two effeminate fugitives get aboard for a wild ride indeed.

So they pack their bags, do up their faces, and change their voices an octave or so higher. They wobble to the train station on top of their heels as Josephine and Daphne, just what the band leader Sweet Sue ordered and our two effeminate fugitives get aboard for a wild ride indeed.

They soon meet the other gals including the vivaciously scatterbrained Sugar Kane (Marilyn Monroe), who already has a strike against her for getting caught drinking. It looks like bad news for her during a bouncy rendition of the 20s tune “Runnin’ Wild.” Amid the toot-tooting of Josephine’s sax and the bass twirling of Daphne, Daphne also finds time to bail Sugar out. She’s quick to make friends too during an after-hours get-together in her compartment. It’s one of the uproarious moments where Jerry/Daphne must go through the battle of the sexes. He’s so giddy to have so much female company and yet he must maintain his facade. What’s brilliant about Lemmon is he actually seem to genuinely relish his part. Whether it’s his character or not I’m not sure, but he buys into his role especially when it comes to his budding romance, but that comes later.

All things are bright and cheery when they arrive in Florida with palm trees and bachelors galore, all ready and waiting for a little tete-a-tete. One such bachelor is Osgood Fielding (Joe E. Brown), who immediately has his eyes on Daphne. And let the comedic irony and romantic entanglements begin. What follows are two absolutely preposterous tales of romance that crank up the absurdity.

Joe swipes a sailor’s cap and a pair of glasses while donning his best/worst Cary Grant impression to woo Sugar as an aloof magnate complete with oil fields and a yacht. It’s all part of his plan to win her love, and Daphne views the whole thing disapprovingly, hoping to catch his buddy in the lie. Thus, now Joe has committed himself to two roles and somehow he’s able to keep the plates spinning by borrowing Osgood’s boat for a romantic night with Sugar and using a bicycle to rush back to the hotel and put on the whole Josephine act.

Joe swipes a sailor’s cap and a pair of glasses while donning his best/worst Cary Grant impression to woo Sugar as an aloof magnate complete with oil fields and a yacht. It’s all part of his plan to win her love, and Daphne views the whole thing disapprovingly, hoping to catch his buddy in the lie. Thus, now Joe has committed himself to two roles and somehow he’s able to keep the plates spinning by borrowing Osgood’s boat for a romantic night with Sugar and using a bicycle to rush back to the hotel and put on the whole Josephine act.

Meanwhile, Jerry gets more and more invested in the whole Daphne performance dodging Osgood’s playful advances, while finally dancing the night away to a killer tango. It’s the diversion Joe needs in his plan to get with Sugar, and he’s succeeding. But Jerry, or should we say Daphne, isn’t doing so bad either. With a flower between her teeth and when she’s not trying to lead, they make quite the couple. Could there be wedding bells?

All that hilarity goes on halt when Spats Colombo and his gang come to town for a conference and the girls avoid suspicion at first, but their nervousness tips the mobsters off. The chase continues and the boys must finally drop the act if they want to get out alive. But Joe delivers one final gesture to Sugar not wanting to ditch her completely. They plan to catch a ride with Osgood who will elope with Daphne. But in a last-ditch effort, Joe finally lets everything drop and breaks all pretenses. It makes for an awkward situation when he gives Sugar a big kiss in front of a full audience, still dressed in drag.

As they get away in the little motorboat, Joe pleads with Sugar not to stick by him, because he really is a bum. But she doesn’t care, does she? He’s Tony Curtis, a Cary Grant type. Now it’s Jerry’s turns as he tries to cook up excuse after excuse why he cannot marry Osgood, and of course every time he’s rebuffed. Finally, in exasperation, he pulls off the wig, loses the voice, and yells, “I’m a man!” Without missing a beat, his beau shoots back, “Well, Nobody’s Perfect.” The look on Lemmon’s face is priceless and this moment is the perfect capstone on one of the wildest films you could ever imagine.

It’s absolutely astounding that despite all the headaches and troubles Marilyn Monroe brought to the set, including constantly flubbing lines and being generally difficult, her performance bubbles over with a playfully ditsy sensuality that captivates the screen. I for one can hardly ever see the turmoil going on underneath because the role of Sugar is so vibrantly joyful, innocent, and genuinely funny put up next to her great co-stars. Her numbers like “I Wanna Be Loved by You” exude the friskiness that she was known for and there’s no question that Monroe has a magnetism on the screen that was unequivocally her.

It’s absolutely astounding that despite all the headaches and troubles Marilyn Monroe brought to the set, including constantly flubbing lines and being generally difficult, her performance bubbles over with a playfully ditsy sensuality that captivates the screen. I for one can hardly ever see the turmoil going on underneath because the role of Sugar is so vibrantly joyful, innocent, and genuinely funny put up next to her great co-stars. Her numbers like “I Wanna Be Loved by You” exude the friskiness that she was known for and there’s no question that Monroe has a magnetism on the screen that was unequivocally her.

Joe E. Brown plays the giddy playboy with devilish hilarity, the perfect comic companion for Lemmon. While Tony Curtis is great, he plays the straight man in the sense, that it feels like he’s just doing this out of necessity. Lemmon is an absolute riot, taking on this role willingly and bubbling over with enthusiasm that is palpable. He has that cackling laugh that adds an exclamation point too many of his conversations and when he starts dancing around with those maracas, shaking his hips, it’s hard not to crack a big goofy smile.

Billy Wilder always had a gift for films with wonderfully entertaining characters and plot lines that poke holes and find humor in modern sensibilities. He gets away with so much by dancing the fine line of what is acceptable for the 1950s and yet he puts it together in such an engaging and uproarious way that it remains a classic. Not just of comedy but of film in general. I’m not ashamed to say that I do like it hot. Although air conditioning is nice every once and awhile.

5/5 Stars

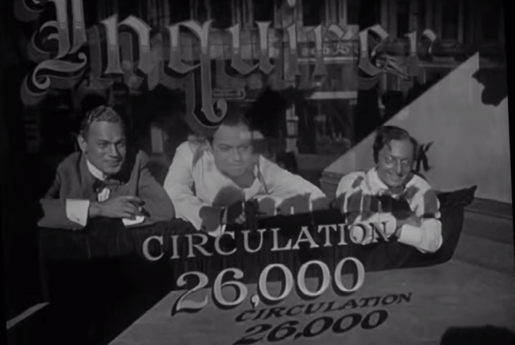

His ambitious follow-up to The Birth of the Nation a year before, D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance boasts four narrative threads meant to intertwine in a story of grand design. Transcending time, eras, and cultures, this monumental undertaking grabs hold of some of the cataclysmic markers of world history. They include the fall of Babylon, the life, ministry, and crucifixion of Christ, along with the persecution of the Huguenots in France circa the 16th century.

His ambitious follow-up to The Birth of the Nation a year before, D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance boasts four narrative threads meant to intertwine in a story of grand design. Transcending time, eras, and cultures, this monumental undertaking grabs hold of some of the cataclysmic markers of world history. They include the fall of Babylon, the life, ministry, and crucifixion of Christ, along with the persecution of the Huguenots in France circa the 16th century. “They say it’s just physical abuse but it’s more than that, this was spiritual abuse.”

“They say it’s just physical abuse but it’s more than that, this was spiritual abuse.”