The Lost Patrol comes out of the colonialist traditions of the era with the white soldiers in Mesopotamia doing battle with an Arab enemy who strike like ghosts. They are phantoms and rarely seen in the flesh. It’s an unwitting bit of commentary but it also simultaneously becomes one of the story’s most unnerving assets. There’s a tension born in an adversary who is all but invisible and still has a deadly sway on the story.

The film’s opening images are telling in establishing setting and the man behind the camera. Because this is a John Ford movie. It’s a fairly early offering, but there are elements that feel unmistakably relevant to his oeuvre. There’s the shadow of horses trotting across the sand, and then a line of riders snaking their way across the wide-open vistas of the dunes. It’s a variance on the western form or at the very least a transplant.

During this journey, their thick-skulled commanding officer is knocked off unceremoniously. He also never thought it prudent to tell his second-in-command what their orders were. With him gone, the remaining contingent is left wandering through the desert wasteland without any kind of direction.

The Lost Patrol is an expeditious drama with little time to waste and so survival becomes its primary focus. It’s not searching out a destination or looking to vanquish the foe as much as it’s about these men living to fight another day. It’s a windswept character piece more than anything.

We see Victor McLagen at his most restrained and sensible. His wealth of experience has taught him to keep his head, and he makes darn sure that all his men stay on high alert. Take, for instance, the euphoric scene where the mirage is real, and they finally settle on a spring of water. The men are satiated by a cool drink — a lifeline in the midst of such an arid and desolate terrain — and they fall into it with joyous elation. Their Sergeant is the one man who holds back, chiding them to take care of their steeds.

If McLagen is one of the stalwarts, Boris Karloff is uncharacteristic as Sanders, a jittery and spiritually inclined fellow clinging to his belief although he seems ever ready to spout off jeremiads. For him, their latest discovery is tantamount to The Garden of Eden.

It is an oasis, but they’re also stuck there. Instead of being excommunicated, they might as well die where they stand if they can’t get support. Much of the film at this juncture comes from digging in and waiting it out. We get to know the band of men and at the time same are brought into the tension of their prolonged campaign of survival.

A young lad, wet behind the ears, is crazy about Kipling and the glories of war. Whereas he’s woefully ignorant of the tough side of the life he’s chosen. Morelli (Wallace Ford) is a bit more jocular blowing off some steam with his harmonica even as he brushes off his own bad luck, calling himself the Jonah of their expedition. Still, their leader doesn’t see fit in tossing him overboard. They’re only going to prevail if they stick together.

Because this is a Ford picture, there also have to be a couple token Irish old boys to round out the company. They’ve seen much of the world thus far, and they have more or less willed themselves to fight another day. It’s baked into their stock.

By far the most intriguing has to be Boris Karloff as he’s taken over by his religious fanaticism. And he’s not the only one to totter toward the precipice of insanity or unrest. There are others. In fact, how does one not lose their mind under such dire circumstances?

Their situation is laden with the kind of dread of a who-done-it murder mystery. Men get knocked off or become lost to the elements, one by one, until their mighty group is dwindling with the unseen enemies still lurking just beyond the sand dunes.

Though the parameters of the drama come out of a bygone era that we have left far behind, somehow Ford’s film maintains some amount of its mystique. He’s already well-versed in capturing the panoramas around him in striking relief. He’s actually aided even more by hardly showing his villain at all. Time honors this decision because it falls away, and we forget the stereotypes as much as we feel the specters hanging over the patrol.

To the very end, McLaglen is a stalwart and you can see how Ford is able to fashion him into a reputable even idealized champion. He’s not unlike a John Wayne or other figureheads Ford found ways to fashion into his personal visions of inimitable manhood. There’s something admirable about them — found in their mettle and loyalty — even as they exude a persistently evident humanity.

3.5/5 Stars

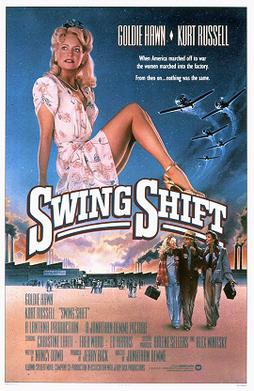

Aside from films actually produced during the war years, I’m not sure if I can think of a film that highlights the homefront to the degree of Swing Shift. The soundtrack is also perfectly antiquated (sans Carly Simon) fitting the era and mood to add another definite dimension. It effectively takes us back with the auditory cues of Glenn Miller, Hoagy Carmichael, and the rest.

Aside from films actually produced during the war years, I’m not sure if I can think of a film that highlights the homefront to the degree of Swing Shift. The soundtrack is also perfectly antiquated (sans Carly Simon) fitting the era and mood to add another definite dimension. It effectively takes us back with the auditory cues of Glenn Miller, Hoagy Carmichael, and the rest.

The opening images of Seven Days in May could have easily been pulled out of the headlines. A silent protest continues outside the White House gates with hosts of signs decrying the incumbent president or at the very least the state of his America. We don’t quite know his egregious act although it’s made evident soon enough.

The opening images of Seven Days in May could have easily been pulled out of the headlines. A silent protest continues outside the White House gates with hosts of signs decrying the incumbent president or at the very least the state of his America. We don’t quite know his egregious act although it’s made evident soon enough.